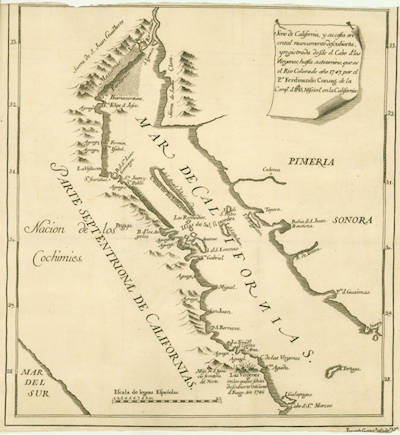

The first important clue is the location of the Manila galleon wreck. Massey placed Kalvalaga farther north, up near El Rosario. That's why

Laylander places it there on his map. In order for that to be true the Manila galleon would have to be much farther north than it is. Aschmann had a

dissenting view, he actually correctly guessed the vicinity of the wreck fifty odd years before it was found. He placed Kalvalaga somewhere west of

Punta Prieta.

The second important clue is Lincks 1766 diary which states Keda (Codornices) was the furthest north Consags expedition went. That can only be one of

the two groups Consag sent out to explore from La Cienega (San Andres). He sent one group to explore east, to Codornices, and another north to where

they had seen smoke, Kalvalaga.

The current name gives it away. Two places with water, Los Ojitos.

|