A story from Choral Pepper: "Santa María Magdalena-In Search of a Mission Legend" and the follow-up

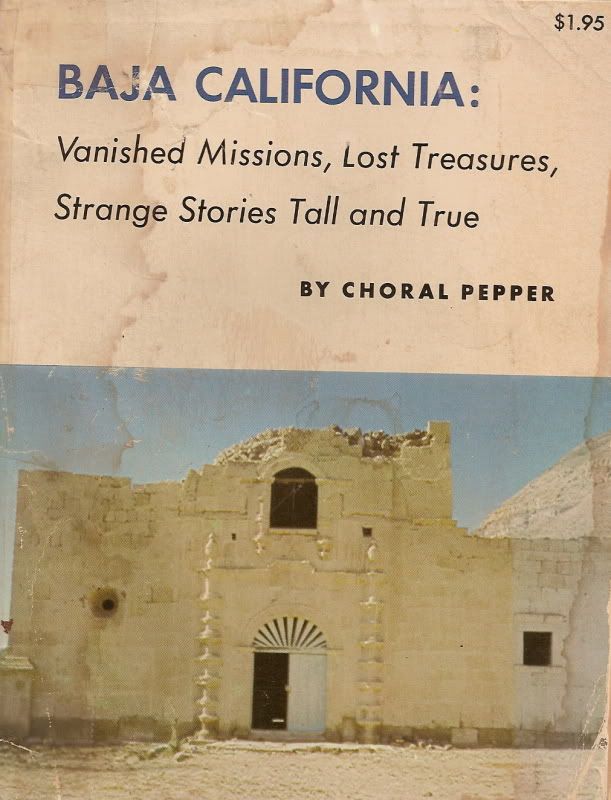

[The following is from the manuscript of Choral Pepper's final book which was an updated version of her popular 1973 & 1975 book on the Baja

mission and other fascinating stories]

From the pen (typewriter/word processor) of Choral Pepper, 2002 >>>

Because this formerly lost site motivated so many requests for directions following its discovery recounted in my early Baja book, I will

describe details of the route as closely as I can recall. I tried to find it again in 1995, but we ran into a storm that partially washed out the

bridge and much of the road that now loosely follows the old Padres Golfo Camino, thus making it impossible to establish a camp and re-explore the

area.

During the 1966 expedition with Erle Stanley Gardner, one goal was to locate a lost mission trail known as the Padres Golfo Camino, believed to follow

along the Gulf coast between Bahia de los Angeles and Punta San Francisquito. As Gardner’s caravan plunged along an abandoned road that once served

the ore mills at Las Flores we speculated, somewhat derisively, upon the ability of a team of drivers for the Automobile Club of Southern California

who reportedly had turned back after about twenty miles. Then we reached the end of that twenty miles! The scene changed.

No longer was there any trail, or even a sign of one. Forests of cardón and spiny Palo Adam set up a cacophony of screeches against our vehicles.

Soft sand spewed and slid under the wheels as we traveled about two miles an hour. And then, like the parting of a sea, it suddenly opened into a

broad sandy wash like a cardón boulevard. Some deserts are hard and rocky, some harsh and black, others brilliant with red and orange. This one was

pastel where gray-blue smoke trees feathered against pink sand and immense cardón reigned in uncrowded splendor. We followed the wash until it grew

shallow and opened into verbena-splashed dunes inshore from the Bahia de Las Animas—a perfect spot to set up camp.

The area we named “Cardón Boulevard” as we retraced the long-abandoned Padres’ Golfo Camino.

A variety of rugged vehicles always accompanied Gardner expeditions. My favorite was a sort of dune buggy we called a “grasshopper” which was

specially manufactured by Gardner’s friend J.W.Black to accommodate Baja travel. Once a campsite was established, we’d all pile into the fleet of

grasshoppers to explore places the larger vehicles couldn’t reach. And that is how we happened upon a site that confounded all of us.

There it was, a primitive dam among rocks and dead trees with a scraggly date palm standing alone. Usually, date palms appear in groves. This one was

relatively young, so must have sprouted from seeds dropped by dead ones.

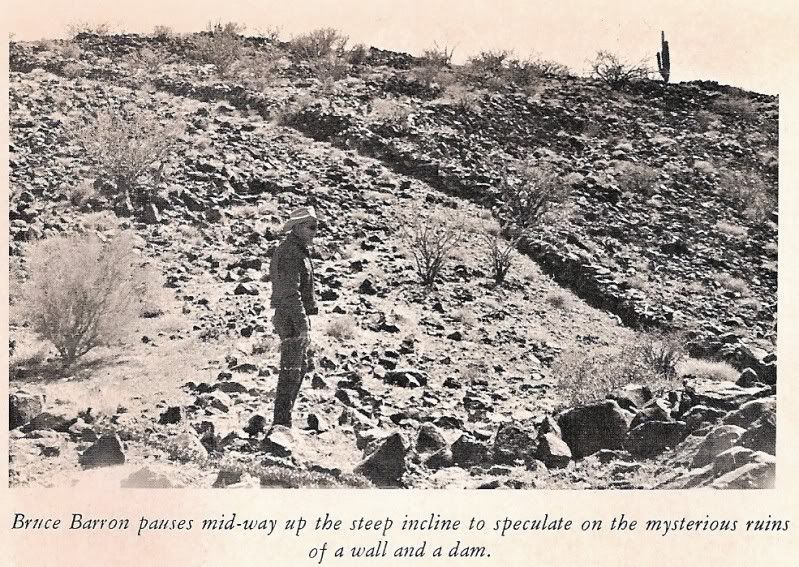

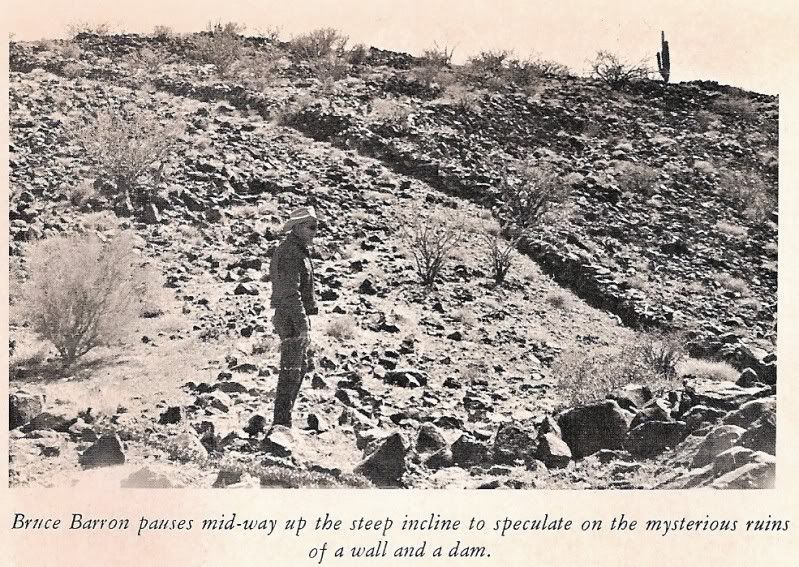

We left our grasshoppers to climb into the ravine and examine remnants of the dam that once held water in a natural reservoir. An ancient wall

half-buried in sand angled from the dam to stretch in broken sections across the level valley. Then, from the other end, a similar wall serpentined up

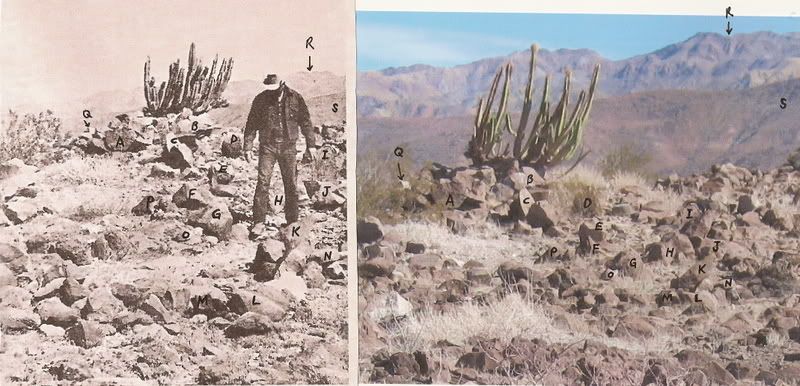

the side of a steep mountain. It was easy to miss, as the stones were coated with desert varnish and melded into the rocky terrain. The upper parts of

the wall, constructed above a thicker base typical of mission trails, remained in only a few places. The top of the mountain appeared flat, but its

sides were steep. From where we stood, we could only guess at a structure on top.

It was a hot day and a climb up the hill uninviting, but somehow, I felt we’d discovered something interesting. Subsequent research proved me right

about that, as established in my earlier Baja books. Today it is generally accepted that this is the old Jesuit mission of Santa María Magdalena,

which was never finished, and which had necessitated the Padres Golfo Camino, later abandoned.

In the first place, the rock-lined wall leading up the steep hill was an enormously ambitious project, much more than Indians native to Baja would

have undertaken on their own. Then, the rocks on the walls were heavily coated with desert varnish, all of it deposited on the upper sides. This

black coating on rocks called desert varnish occurs in desert regions all over the world, often on the faces of rocky cliffs as well as on rock

covered ground. European scientists refer to it as Dunkel Rieden and believe it is caused when rainwater soaks into the rock and is then brought back

to the surface by capillary action of the sun. Here it evaporates, leaving a deposit of the chemicals with which it becomes charged according to the

composition of the rock itself. If there is too much moisture, it departs the rock in liquid form and carries the salts with it. If there is too

little moisture, salts are not dissolved to form the varnish on top while unexposed sides remain natural. In desert climates like Baja, it can take

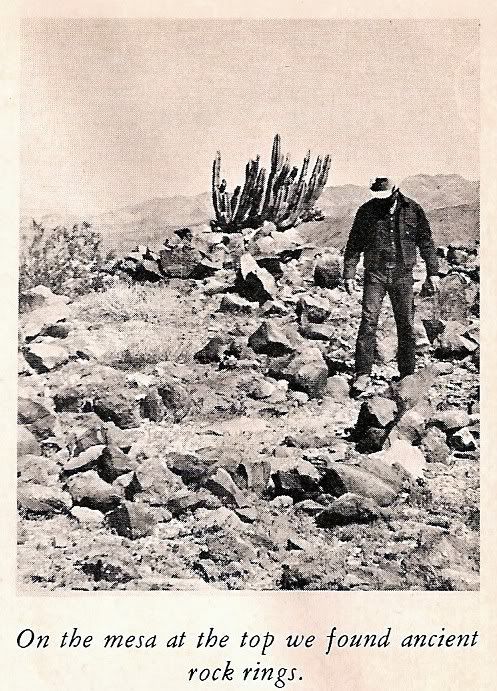

many centuries to form. In less than several hundred years the tops of all these rocks would not have tanned to the same degree. On the plateau at the

top of the mountain, the wall continued around the edge, but in several areas, there were large piles of rock, that appeared to have fallen, or been

knocked down, from a larger structure, possibly a lookout tower.

We were intrigued by a series of rock rings grouped in a colony at the far end of the plateau, some with adjoining openings as if to designate

separate rooms. Early Baja natives connected with the missions often lived in circular pens of stones, sleeping on the bare ground. Eroded clamshells

lay among the rings, suggesting the pens had held people, not cattle.

In view of extensive walls in the now arid valley below and the number of huge old trees, many dead, there must have been a live spring dammed there

at one time. Walls designed to confine cattle as well as the presence of a date palm clearly indicated missionary direction. But historical as well as

physical evidence re-enforced my identification of the site as Santa María Magdalena.

Following a number of Indian insurrections and the destruction of mission properties in 1742, the King of Spain ordered a presidio erected and

instructed the Council of the Indies to propose a plan for the pacification of the whole Baja California territory. As a result, four recommendations

were made, which King Philip V accepted and embodied in a decree dated 1744. These stated that the missionary work of the Jesuits should be continued;

that colonies of Spaniards should be founded near all convenient ports and protected by military posts; that to make quicker conversions among the

natives, missions should be established in the north of the peninsula and united with those of the south; and that the number of missionaries should

be doubled. In return, a complete report and description of missions and mission stations was to be drawn up and sent back to the King.

It was from this report, dated 1745, that we learned Indians had been converted by Padre Fernando Consag and the mission of Santa María Magdalena

begun to the north of existing ones. The Venegas map it is identified as “Misión de Santa María Magdalena, empezada” (empezada means

“begun”) at about latitude 29 degrees and within a few miles of the Gulf. No subsequent reference was ever made of this mission and it was not

among those inherited by the Franciscan Order after the Jesuits had been banished from New Spain by the King, as explained earlier.

Judging from the ruins we examined, it appeared likely the original plans had been aborted and the project never completed. However, the plateau atop

the mountain offered an ideal lookout for a military post and it was located close to two convenient ports—those of Bahía de los Angeles and Bahía

las Animas—in line with the demands of the King. An existing mission trail followed up the center of Baja before crossing to the Pacific Coast, but

at the time Mission Santa María Magdalena was instituted, the padres were interested in the Gulf coast, hoping to establish land contact with the

missions of Sonora. No previous Gulf trail then existed. When the mission was abandoned for one reason or another, so was the Golfo Camino, which we

were now resurrecting.

Author Arthur North wrote in his Camp and Camino in Lower California about a visit in 1906 to ruins of a Jesuit mission chapel named Santa María de

la Magdalena about six miles south of Santa Rosalia. However, Peter Gerhard and Howard E. Gulick in their superb Lower California Guidebook referred

to those same ruins as remnants of the Magdalena chapel built by the Dominicans in 1774. They don’t refer to them as a mission at all, which makes

good sense considering that the Dominicans didn’t even get to Baja until 1773 and their first mission, established in 1774, was much further north

on the Pacific coast. The Jesuits began the Santa María de la Magdalena mission on the Gulf as indicated on their 1757 map. Because further reference

to the mission is ignored in other records of importance, I am inclined to believe the ruins south of Santa Rosalia were never a mission, but instead

are those of an early Dominican chapel established to serve rancheros and mines in the productive Magdalena and Santa Rosalia mining area.

In some stretches of this virgin area, we noted occasional rows of desert-varnished rocks typical of those outlining known mission roads used by pack

trains to transport supplies and messages from one mission to another. Otherwise, nothing indicated the land had been traversed by more than a coyote.

One bad spot, where we came close to giving up, sliced so sharply down into a deep wash that the men worked for over three hours alternately shoveling

and rebuilding the bank into a grade. To negotiate this kind of country, trucks should be hinged in the middle, so they bend.

The Automobile Club of Southern California has long since made it through and its map now indicates a dirt road that extends south from Bahia de Los

Angeles.

===============================================================

From Desert Magazine (July 1966) of their discovery. Photos taken by Choral Pepper who climbed up the side of the mesa with Bruce:

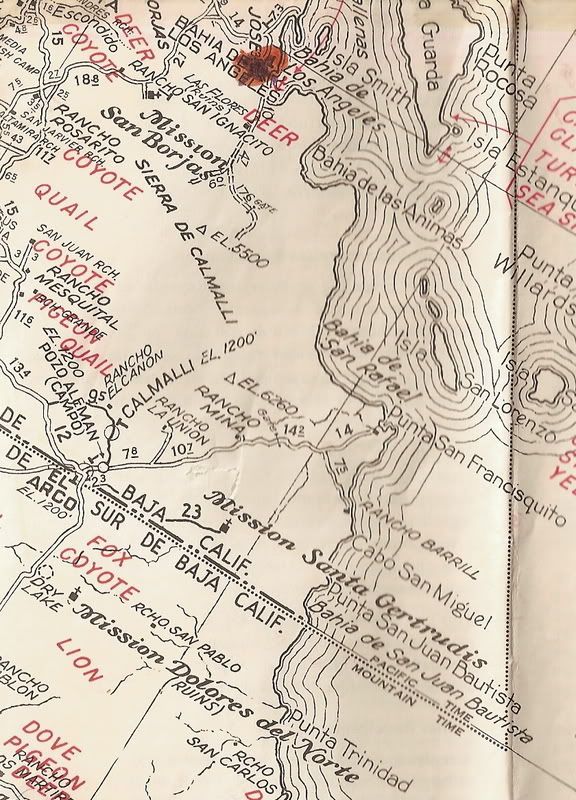

The auto club map of the mid 1960s:

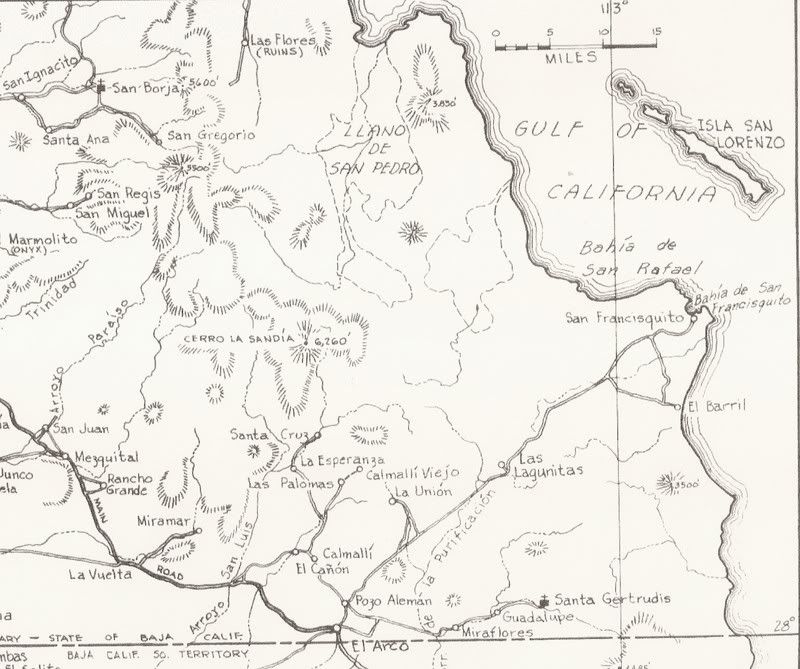

The Gulick map of 1962:

================================================================

To find this site only to have lost it again made the rediscovery of it important to Choral. This was one of the lost mission stories I had always

wanted to solve and made several searches, some with other Nomads, for it from 2001-2003. In 2009, Nomad 'Sharksbaja' examining Google Earth found

some odd lines on a hill and asked me if that could be what Choral found... I said I had to go there and find out! Within a few weeks, my wife and I

were southbound, 43 years after Choral Pepper was there!

These photos are from January 2009... Some newer Nomads may enjoy this historic adventure if they never read the 2009 trip report.

First, we found a dam and reservoir:

Then we found the scraggly date palm:

Then a wall vanishing across the desert:

Then, driving on and looking up...

We had to climb up, as Choral and Bruce had, 43 years before!

What was its purpose?

That's Bahía las Animas, the shore is 2 miles away.

Sleeping circles, containing sea shells, just as reported:

In 43 years, rocks don't move much and cactus doesn't grow much!

Perhaps one of the most exciting discoveries we have made was to re-find this site described by Desert Magazine's Choral Pepper during the 1966 Erle

Stanley Gardner expedition to re-open the Golfo Camino in order to drive from Bahía de los Angeles to El Barril/Punta San Francisquito.

While some authors have credited this discovery as being the site of Mission Santa María Magdalena, from the 1757 Jesuit map, there is no other

evidence yet found. However, a bell now hanging at the nearest mission to the south contains the name "Santa María Magdalena 1739"

May-be???

Discoveries like this are just another reason to go to Baja, the original California!

Read more about Choral Pepper in this article: https://www.bajabound.com/bajaadventures/bajatravel/choral_p...

[Edited on 6-21-2018 by David K]

|