Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3145

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

Don Gaston Vives and the CCCP

(Unless otherwise referenced, the information presented here was obtained from Micheline Cariño's two books listed below.)

Some background info: Ever since showing up on the European radar in the mid-1500s, the waters off Baja California’s Gulf Coast have been known

for their bounty of pearls. Until recent times, two types of pearl-bearing oysters have thrived there; the pinetada mazatlantica (locally known

as the madre perla) and the pteria sterna (called concha nacar by locals). The madre perla has always been considered the more

beautiful and desirable of the two, giving it a correspondingly greater value. During the first three-and-a-half centuries of pearl fishing in

peninsular waters, the supply of these two oysters seemed inexhaustible, and for good reason. Divers of that era could only go as deep as their lungs

would take them, which ruled out reaching and plundering the deepest oyster beds of the Gulf. When left alone for four or five years, depleted beds in

shallower waters were repopulated by larvae from the out-of-reach oysters. Divers’ physical limitations effectively made the harvesting of pearl

oysters a sustainable industry.

That all changed in 1874 when the first diving suits were introduced to the peninsula. The new equipment meant that even the deepest banks of oysters

were reachable, with predictable results. Within seven decades most of the madre perla oyster beds had been devastated to the brink of extinction and

the concha nacar soon followed. In 1939 the Mexican government declared these two oysters endangered species and placed a permanent ban on their

harvesting, bringing to an official end an industry that had established family fortunes and provided a livelihood for residents of the region since

the founding of the city. (Even with the ban in place, Fernando Jordan reported commercial harvesting of pearl oysters taking place in the Gulf in

1950 [Jordan:271].) In an ironic twist of fate, the madre perla oysters in the waters of the Gulf of California staged a mass die-off the same year

they gained protected status. Although this wasn’t the first time that a mass die-off of oysters in the Gulf of California had been recorded

(Martinez:287), the intensity of their harvesting in the years preceding this calamity left fewer oysters in the Gulf and their relatively small

numbers likely contributed to their inability to recover as they had in the past.

But for a couple of decades around the turn of the twentieth century, it seemed that one man had the solution for preventing the loss of this valuable

resource. This is the tragic story of don Gaston J. Vives and the CCCP, the company he founded.

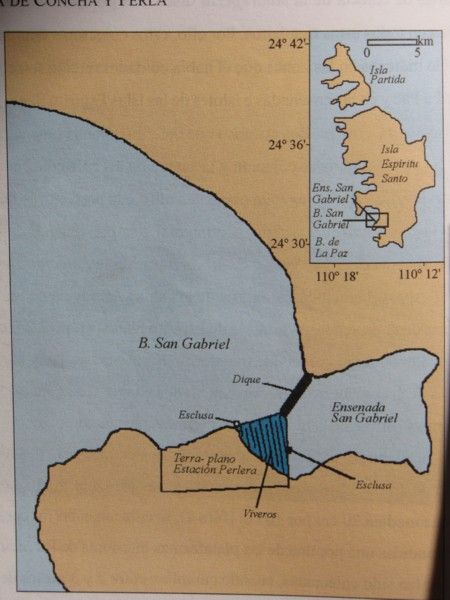

During the first decade and a half of the 1900s Espiritu Santo Island (which is visible from La Paz at the north end of the malecon) was at the center

of a regional industry that thrust La Paz and one of its most illustrious residents onto the world stage. From 1903 until 1914 the Compañia

Creadora de Concha y Perla (CCCP) (Pearl and Shell Raising Company) had its main field operations at San Gabriel Bay on the southwestern end

of the island. As its name implied, the company was involved in the pearl and oyster shell business (at the time, oyster shells were in much demand in

the United States and Europe for making buttons, combs, ornaments and other trinkets and for inlaid work). But what set the CCCP apart from every

other enterprise that had sought to exploit pearl oysters in the Gulf of California was that don Gaston’s company was the only firm that also

repopulated the harvested oyster beds with juvenile oysters. In fact, the CCCP was the first successful effort to artificially cultivate pearl oysters

on a commercial scale anywhere in the world—although the Japanese are erroneously credited with this accomplishment (Cariño 1999:119). The

man responsible for the CCCP’s success was don Gaston J. Vives, a local entrepreneur, inventor, scientist, and politician.

There is some doubt as to where Vives was born. Some sources speculate that he might have originally been from the US East Coast or perhaps New

Orleans while others say he was born in San Francisco and was three years old when the family relocated to La Paz in the late 1850s. Yet his Mexican

passport stated that he was born in La Paz in 1859. What is certain is that, although both his parents were French, Vives was 100 percent

Paceño (a native from La Paz)—if not by birth, then in his heart. His parents ensured both their sons were fluent in French and English as

well as Spanish. The family owned a restaurant, a bakery and “some pool halls” during their early years in La Paz (Cariño 2000:25). Don Gaston’s

mother likely had some personal wealth as well, since she purchased several valuable properties in the region.

His Student Years

When Vives turned twenty, his parents sent him to France to study medicine and to expose him to the customs and traditions of the Old Country. Once in

Paris, however, Vives found that medicine didn’t interest him much. What really caught his fancy was the new field of biochemistry, which he took up

with zeal. In the 1800s France was a world leader in scientific research and at the time of young Gaston’s stay aquaculture and the reproduction of

bivalve mollusks was an important field of study—although the mollusks of interest were of the eating variety, not of the pearl-bearing types. Vives

no doubt realized the implications of what he was learning for his hometown. In La Paz, his view of the pearl business had been from the production

end of things, of the expeditions of ships and canoes (called armadas locally) leaving and returning to port during the summer fishing

season, of the hardships the divers, line tenders and the rest of the crews suffered to bring the sought-after product to market. In Paris, Vives

learned how the top end of the international pearl bazaar worked since the city was then a leading player in world trade of the gemstone.

The Scientist and Inventor

Vives cut his stay in France short when his father passed away, returning to La Paz to manage the family’s business interests. In 1889 he took his

first step into the pearl business when he and his brother Edmond founded the Compañia Perlífera del Golfo de Cortés (Gulf of Cortez Pearling

Company), and managed to get one of the prized concessions to exploit the madre perla and concha nacar oysters. The concession gave the brothers

exclusive rights to the pearl beds at San Jose Island in the northern reaches of the Bay of La Paz. Notwithstanding that his brother was listed on the

corporate paperwork as the company’s senior official, it was don Gaston who called the shots.

Although the company’s primary objective was the commercial harvesting of pearl oysters, don Gaston’s chief interest was to understand everything he

could about the mollusks. He spent countless hours in diving gear studying them in their natural habitat, recording the details of their lifecycles.

He took note of the types of environments that favored them most and mapped the bay’s currents, discovering in the process how the oysters’ seedlings

propagated. He learned about their vulnerabilities and which species were their natural enemies at different stages in their development.

As he learned, he experimented and built and refined prototypes. For capturing oyster seedlings, he designed devices that recreated the natural

environment in miniature. He built what he called incubadoras (incubators) to raise the captured seedlings within the two estuaries, where

they were cared for until becoming juvenile oysters. A stumbling block that had befuddled other scientists was getting juvenile oysters from their

nurseries into deeper waters to reach maturity. An unacceptably high number of them died before reaching distant beds. Don Gaston solved the problem

by building what amounted to a large compartmentalized cage that was slowly dragged behind a tow ship. Once they had been deposited in oyster beds in

the open waters of the Gulf, they were left to mature for four to five years before they were harvested for their pearls and shells. To ensure that

transplanted oysters had decent odds of reaching maturity, Vives designed a type of tin armor that looked like two ninja throwing stars attached at

one point that kept the juveniles safe from most predators during their peak period of vulnerability. Although the company enjoyed considerable

success on San Jose Island and Vives’s experiments produced impressive results, don Gaston wasn’t yet satisfied. His studies of the currents

circulating in the Bay of La Paz indicated that, although San Jose Island was a good place for his ideas to flourish, the real prize lay some 20 miles

south, at Espiritu Santo Island.

Don Gaston and the politics of his time

But Vives didn’t limit himself to his scientific activities on the Bay of La Paz. Don Gaston was active in local politics and was an unabashed

supporter of Porfirio Diaz and the Porfiriato (1876-1910), which was a time of unprecedented development and economic growth in Mexico (Simpson).

During all of its short history as an independent nation prior to the Diaz dictatorship, the political scene in Mexico had been chaotic. In the

decades after Mexico gained its independence, coup d’états' were a national sport as conservatives supplanted liberals who had supplanted

conservatives who had…. One highly charismatic but supremely incompetent general was used as a figurehead president eleven non-consecutive

times during this period in the nation’s history—never completing even one of his terms (Simpson). And each time the central leadership of the nation

changed, so too did the leadership at each level of government all the way down to state and territorial municipalities.

While today the Porfiriato is best remembered (as taught in the national school books in Mexico) as a brutal three-decades-long period of dictatorial

rule, it was also the first era of political stability for the young nation. The political turmoil that existed prior to Diaz’s election impeded any

serious economic development in most of the country, keeping Mexico a backward nation. During the stability of the Porfiriato years, Diaz’s

“technocrats” introduced an economic development program that was heavily reliant on foreign investments to modernize the nation. While the Porfiriato

was great for investors and the nation’s ruling elite and their associates, it wasn’t so hot for most of the nation’s working poor, who were brutally

suppressed when they dared question the low wages, long hours, or bad working conditions (Simpson).

While the dictator ruled with an iron fist in much of Mexico, in La Paz the results of the Porfiriato were overly positive (Preciado Llamas 2005).

Locally there were no large factories exploiting workers or big haciendas trampling on peons (although there were frictions in the Southern Mining

District [San Antonio/El Triunfo], the nearest source of real strife on the peninsula was at the Boleo mining town at Santa Rosalia). During the

Porfiriato things were tranquilo (peaceful) in La Paz.

This satisfaction with the status quo was made clear in 1879 when General Manuel Marquez de Leon, a local boy, rose up to challenge the legitimacy of

Diaz’s second administration. The General had ridden with Diaz in wars and had expected a handsome reward once don Porfirio assumed the presidency.

When he didn’t get it, the General tried to generate a local revolt against Diaz to create momentum for an eventual march on Mexico City (Preciado

Llamas 2003: 407). When he found little regional support, he had to abandon his plan and seek refuge in the United States. A few of his followers were

arrested and jailed for a while, but little else of consequence happened.

The Porfiriato was the flipside of the same political coin that required local government officials leave office in synch with the frequent changes in

national leadership. During most of Diaz’s rule, there was little local political mobility. Those who were identified with the president tended to

stay in office or, if they did leave, it often was to assume another political position. Don Gaston Vives served as municipal president for roughly

two decades of the Porfiriato. At times, he even covered for the jefe político (political boss, who was appointed by the federal government

to rule over peninsular matters) during his absences.

In addition to his duties as municipal president, Vives also served as the Deputy of Mines for the Southern District and the Italian Kingdom hired him

as its local representative (in those days, it was a common practice for foreign governments to hired educated local citizens of high

reputation—especially if multi-lingual—to represent them locally).

Although Vives didn’t receive a salary as municipal president, there were other benefits to the position. The speed with which he was able to obtain a

concession for pearling on San Jose Island was likely a result of his political activities. As might be expected, those who were out of favor with the

politics of the Porfiriato were not happy campers and were the enemies of those who were “in.” One of the enemies don Gaston made while serving as

municipal president was a local pearler, entrepreneur and businessman named Miguel Cornejo.

Cornejo and his brother Carlos had been among the few who supported the aborted uprising of General Marquez de Leon in the early years of the

Porfiriato. Miguel Cornejo was arrested, tried and convicted for his participation in the uprising and sentenced to serve six months in prison at

Mazatlan. Upon his return to La Paz, Cornejo concentrated his frustration on those who represented the Diaz government locally, among them don Gaston

Vives. One early evening in March of 1895, Vives and Cornejo were both out for a stroll at the town plaza in front of the church, each accompanied by

friends. When Cornejo spotted his detested opponent, he asked Vives if the municipal president would give him a minute of his time. Vives agreed and

the two men separated from their respective groups. Once aside, Miguel expressed his displeasure over a municipal ruling that he felt was prejudicial

to his interests. When don Gaston professed not to know what he was talking about, Cornejo sucker punched him, knocking Vives to the ground and

kicking the downed man. As municipal president, Vives was required to carry a weapon, which he fired into the air to call his friends to his aid.

Cornejo was again arrested, tried, convicted and placed behind prison bars. Although the whole fiasco must have been unpleasant for Vives at the time,

it was but a prelude to the aggression that Cornejo would one day unleash against him.

Don Gaston’s good relations with the central government and General Sangines in particular (the jefe politico for most of Vives’s tenure as municipal

president) meant that the city benefitted from generous federal expenditures during his administration. Some of the more notable improvements in the

city that took place during his tenure were the opening of the city’s first hospital (the old Hospital Salvatierra on Madero Street in the Esterito,

now a Casa de la Cultura), the building of the old Municipal Palace on Calle 16 de Septiembre and the Teatro Juarez on Belizario Dominguez. Vives also

pushed to close the two cemeteries that were once located in town and opened the cemetery of Los San Juanes, which is still in use today. He is also

credited with the first cobble-stoning of the city’s downtown.

The Entrepreneur and the CCCP

Once Vives had perfected his pearl-raising technology on San Jose Island, he sought out don Antonio Ruffo, a prominent local man of commerce who was

also a pearl armador (in this case, a person who organized and financed pearling expeditions). Ruffo held the concession to Espiritu Santo

Island, which had been known as the Island of Pearls since the time of Cortez (Martinez 2003:126). In his studies of the propagation of pearl oyster

seedlings, Vives realized that the waters around the islands comprising “Espiritu Santo Island” contained some of the best habitat for raising pearl

oysters and the bay’s currents favored those beds for repopulation. Impressed by what don Gaston had to say, Ruffo placed his pearl concession at

Vives’s disposal and, together with don Gaston’s brother Edmond and three other local entrepreneurs, founded the CCCP. The year was 1903.

On the southwestern end of Espiritu Santo Island is a small cove named San Gabriel Bay, which is where don Gaston set up the company’s principal base

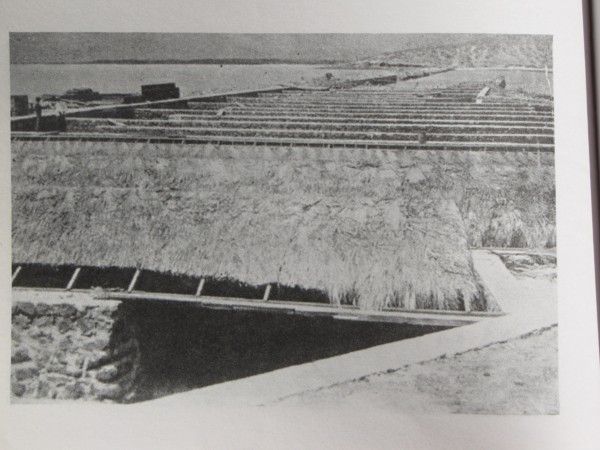

of operations. Vives enclosed a section of the inner bay at San Gabriel by building a 500 meter-long dike. A mangrove was located at one end of the

dike and that is where Vives built a series of 36 interconnecting canals. The dike had two portals through which water was admitted into the inner bay

while the tide rose. Once the tide was high, the portals were closed and two portals that connected the 36 canals to the outer bay were opened,

allowing the dirty water from the last cycle to flow out while drawing oxygen-rich water from the inner bay, through the mangrove, where it picked up

nutrients before entering the “nursery” composed of the 36 canals.

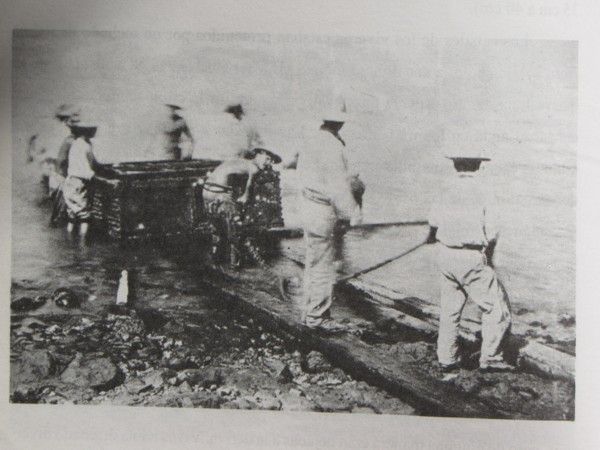

At the San Gabriel Station, Vives transferred the young seedlings caught in the Bay of La Paz into large baskets and set them in the canals, where

they spent a two-to-three month incubation period. After that, the juveniles were placed into compartmented baskets where they were allowed to grow

till reaching eight or nine months of age. The juveniles were then fitted with a protective armor before being transferred to pearl beds in the Gulf,

where they were harvested after reaching maturity. The armor, made out of tin, corroded away as the oyster matured.

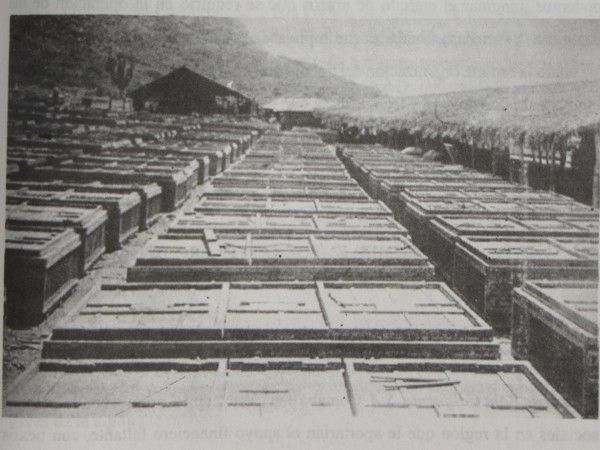

While pearls were always hoped for during the harvests, the real moneymaker for the CCCP was nacre, as pearl oyster shells are known. Interestingly,

the literature doesn’t mention Vives having any desire to create cultured pearls—which is the art of inserting a substance into live oysters to

artificially induce them to produce pearls. The CCCP only produced naturally-forming pearls. Vives became a regular at the yearly pearl exchanges held

in New York and Paris, where he often took the finest examples the CCCP had produced to sell.

The CCCP was so successful in its endeavors that don Gaston soon had workers on Espiritu Santo breaking up rocks to be deposited into the surrounding

sea to create more habitat for his young juveniles to be transplanted. At the height of the company’s operations, it reportedly produced annually

between 200 and 500 pearls of superior quality and up to ten million oyster shells (Cariño 1999:169). The company grew to have nearly 600 employees,

or almost ten percent of the town’s population. Most of them worked at the San Gabriel Station. During elections, the local government operated voting

booths at San Gabriel to ensure the workers weren’t deprived of the right to vote (and which likely produced results quite favorable to the political

ambitions of Vives).

To provide for the needs of the company’s workforce, don Gaston also cultivated on dry lands. He made extensive use of the lands he and his mother

owned to grow fruits and vegetables and cattle to feed the company’s workers. He is also the person responsible for introducing goats onto Espiritu

Santo Island (the descendants of these were recently removed from the island at great cost to the government, which wants to restore the island’s

original habitat). When they weren’t needed for placing juvenile oysters in their beds or harvesting mature ones, the company’s ships were used to

transport goods and passengers to and from the mainland. Don Gaston appeared to have all of the angles figured out to maximize the efficiency of his

operations. But one thing he didn’t factor in was the level of animosity his enemy, don Miguel Cornejo, felt towards him.

The Sad End

When the dictator Diaz was finally overthrown in 1910, don Gaston was asked by his political enemies to resign from his post as municipal

president—which he promptly did. He spent the next four years concentrating his efforts on improving the CCCP’s operations in the bay of La Paz. The

company’s production took off and all indicators pointed to increased success in the future.

On the national stage, everything seemed calm after Diaz departed the scene. Francisco I. Madero had assumed the presidency in a surprisingly peaceful

change of administrations. Little changed for most of the nation as Madero wasn’t interested in radical changes to the overall society. But when

President Madero and Vice President Pino Suarez were assassinated, the nation quickly deteriorated into chaos as several men and their armies competed

for the “presidency” (Simpson).

Vives’s arch nemesis, Miguel Cornejo, took advantage of the situation and travelled to the mainland for an interview with the General Alvaro Obregon,

who was in military control of NW Mexico. The general, unaware of the actual situation on the peninsula, was impressed enough with Cornejo to offer

him a commission as a coronel and sent him back to the peninsula to keep the peace at the head of a contingent of Yaqui troops. But keeping the peace

wasn’t what Cornejo had in mind. On the way back to La Paz from Sinaloa, Cornejo had the ships stop at the installations of the CCCP on Espiritu Santo

Island, where they looted and destroyed as much as they could before heading to La Paz. The oyster beds that had been so carefully groomed by the

company were looted and destroyed by Cornejo’s men, using the CCCP’s own diving equipment to accomplish the mission. Once in the city, Cornejo and his

henchmen headed for don Gaston’s house on the malecon and did a re-do of what had been done to the installations at San Gabriel Bay, dynamiting the

safe and destroying all that they didn’t take, including Vives’s personal library of over 1,000 scientific books.

Vives, who had gotten wind of what was happening, hurriedly left his house ahead of Cornejo’s mob, crossed the malecon and dove into the bay and swam

to the Mogote. Once he reached the sandspit a half mile off the city’s waterfront, don Gaston met a fisherman who gave the desperate man a ride in his

canoe to the US Naval Base at Pichilingue Harbor where Vives bordered a US warship that took him to safety in the United States.

Vives spent the better part of three years living abroad before daring to return to Mexico City, where he began his long fight to recover what had

been illegally taken from him. It was a fight that he would spend the rest of his life waging, to no avail. He was equally unsuccessful at raising

money abroad to continue his life’s work since the world was at war. Even after the cessation of hostilities, don Gaston found no takers as the

Japanese had made great inroads and became the latest rage in the industry. Vives lived out his remaining years in financial ruin, unable to stop the

deterioration of the properties he had left.

In what is a final bit of irony, Vives died in 1939, the same year that the federal government declared the oysters he so cherished an endangered

species under federal protection. 1939 was also the year that most of the remaining oysters in the Gulf of California died off. Thus ended on of the

most promising scientific endeavors the Baja California peninsula has ever been witness to. Ironically, don Gaston has received much more attention

internationally than from his own nation.

Today, the ruins of what was once the San Gabriel Pearling Station can still be found. Although nothing but some copper pieces and nuts and bolts is

left of the great palapas that once provided shade for workers, a visitor can still see the canal works that once dominated the station. In their day,

these, too, were once covered with palapas to provide the young oysters shade and a means of controlling the temperature of the water. They are quite

impressive, really. While the shore in front of the ruins is rocky and not a good place to beach a boat, the swim to shore is easy as there usually

aren’t any waves. While the ruins aren't usually a stop for the pangas that take tourists to Espiritu Santo Island, pangueros are happy to make the

stop if requested to do so. It is a stop worth making.

References:

Cariño Olvera, Martha Micheline. 2000. El Porvenir de la Baja

California Está En Sus Mares: Vida y legado de don Gason

J. Vives, el primer maricultor de América. La Paz: UABCS.

Cariño Olvera, Martha Micheline y Mario Monteforte. 1999. El

Primer Emporio Perlero Sustentable del Mundo: La

compañía Criadora de Concha y Perla de Baja California

S.A. y perspectivas para Baja California Sur. La Paz: UABCS.

Jordán, Fernando. 2005. Mar Roxo de Cortés: Biografía de un

golfo. Tijuana:UABC.

Martínez, Pablo L. 2003. Historia de Baja California Edición

crítica y anotada. La Paz: UABCS.

Preciado Llamas, Juan. 2005. En la Periferia del Régimen:

Baja California Sur durante la administración porfiriana.

La Paz, BCS: UABCS.

_______. 2003. El porfiriato en Baja California Sur. In Historia General de Baja California Sur, II.

Los Proceso Políticos. Edith González Cruz, general coordinator and María Eugenia Altable, volume editor. La Paz: UABCS.

Simpson, Lesley Byrd. 1971. Many Mexicos. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

*All B&W photos reproduced from M. Cariño's books

Photo of the tragic hero of this essay, don Gaston Vives

Placing Espiritu Santo Island (ESI) in context in terms of its location to La Paz

Location of San Gabriel Bay on ESI

Diagram from Cariño's book of the installation

Two bird's eye views of the San Gabriel Bay Pearling Station

How the ruins of the 36 canals look today

Device used to capture oyster seedlings being hauled up to the CCCP installation at San Gabriel Bay

Shaded area for workers, once many of these were in place at San Gabriel Bay

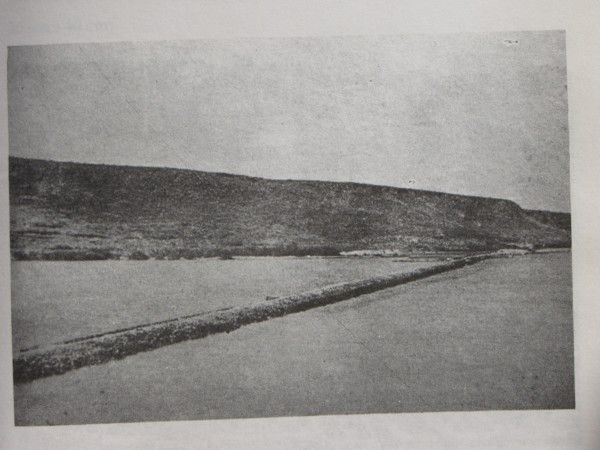

Dike at San Gabriel Bay

Photo of the dike today

Breach in the dike

Shades over canals helped regulate the water temps within the canals. Note the dike in background

Boxes loaded with nacre ready for shipment to US and European markets

Protective "armor" for oysters, the rectangular device on top is a cork that was used to ensure that the oysters landed right-side-up in the beds

The villain in this tragedy, Miguel Cornejo

[Edited on 7-8-2012 by Bajatripper]

[Edited on 9-28-2013 by Bajatripper]

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

woody with a view

PITA Nomad

Posts: 15937

Registered: 11-8-2004

Location: Looking at the Coronado Islands

Member Is Offline

Mood: Everchangin'

|

|

nice read!

|

|

|

willardguy

Elite Nomad

Posts: 6451

Registered: 9-19-2009

Member Is Offline

|

|

although the mexican fishermen believed it was the japanese poisoning the sea of cortez to make their cultured pearls more attractive that killed off

the oyster, now most believe it was the diverting of the colorado river water changing the salinity of the SOC ( with the building of hoover dam the

final blow) that caused the die off.

hoover dam-the submarine in san felipe! its all coming together!!!!

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3145

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by willardguy

although the mexican fishermen believed it was the japanese poisoning the sea of cortez to make their cultured pearls more attractive that killed off

the oyster, now most believe it was the diverting of the colorado river water changing the salinity of the SOC ( with the building of hoover dam the

final blow) that caused the die off.

hoover dam-the submarine in san felipe! its all coming together!!!!

|

One comes across the "Japanese poisoned them so they couldn't compete with their artificial pearls" line a lot in this literature. The argument

against that reasoning is that, even today, scientists doubt that any substance could have been so selective in what it killed, yet nobody reported

other species as having die-offs in 1939. My thinking is that the Law of the Commons applies here and people just kept at them until all the

major beds were devastated beyond recovery. This view is supported by Jordan's report.

Today there are still pearl oysters, but one doesn't usually see beds of them anymore since even these few are likely harvested by divers looking for

other things but not passing up a chance at trying their luck.

I've also heard the Colorado River dam theory a bit. But, as I stated above, this wasn't the first time that a massive die-off of the oysters had

occured. The Jesuit historian Francisco Clavijero reported a massive die-off around 1744 or so. Pearls washed up on the beaches of the mid-peninsula,

there for the picking up. Must have been nice!

I also find it interesting that Fernando Jordan reported massive pearl harvests taking place in 1950 around San Francisquito in the mid-peninsula,

which goes against the pearl oysters all dying off in 1939.

As a kid living in La Paz in the 1960s, I remember local fishermen bringing pearls to our house in the hopes of a sale. If money wasn't too tight, Mom

would buy, but usually not--so they're still out there, just not in the numbers that they once were.

Micheline Cariño's husband, Dr. Mario Monteforte, has been successful at raising pearls in the Bay of La Paz in contemporary times, so perhaps we'll

one day see a resurgence of this lost treasure of the Gulf of California. At the tourist gift shop at Parque Cuauhtemoc (the triangular park on the

Malecon and Bravo street),they have good info on recent pearl-raising efforts in the Bay of La Paz.

[Edited on 7-8-2012 by Bajatripper]

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

willardguy

Elite Nomad

Posts: 6451

Registered: 9-19-2009

Member Is Offline

|

|

rats! then I guess you're not buying the legend of mechudo either?

|

|

|

The squarecircle

Nomad

Posts: 173

Registered: 11-28-2004

Location: El Cajon

Member Is Offline

Mood: 'Baja Feeling'

|

|

Hi Steve, >>>> Thank you for that history of rowdyism. >>>> That is one incredible research and read, Steve. >>>>

Also, thanks for your valuable import on the Timbabichi Trek. >>>> As it may appear in the don Gaston Vives vs. Miguel Cornejo the

'skinhead' won that life long episode proving that yes, 'guano does happen'! >>>> Best Regards, sq.

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3145

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by willardguy

rats! then I guess you're not buying the legend of mechudo either?

|

Ah, yes, the Legend of El Mechudo. One of my favorites! I once saw that legend depicted in a drawing, with a giant clam that doesn't exist in the Sea

of Cortez holding the poor guy under. Still, I can't help but think of it whenever I happen by that area of the Bay of La Paz.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3145

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by The squarecircle

Hi Steve, >>>> Thank you for that history of rowdyism. >>>> That is one incredible research and read, Steve. >>>>

Also, thanks for your valuable import on the Timbabichi Trek. >>>> As it may appear in the don Gaston Vives vs. Miguel Cornejo the

'skinhead' won that life long episode proving that yes, 'guano does happen'! >>>> Best Regards, sq. |

You are very welcome, Roy, on both accounts. Had a pleasant visit recently with David K, whom you had also recently visited. We couldn't help but talk

about you a bit

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

Jack Swords

Super Nomad

Posts: 1094

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: Nipomo, CA/La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

|

|

Very nice job Steve. I had seen the "works" at San Gabriel and knew some of its history, but wow, such a background. Now I have to go back, sit on

the shore, and contemplate again the wonderful history of Baja California. Thank you.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 64479

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

It is great stuff... Baja history, and it keeps getting better!

Roy, don't worry... it was all good! (our conversations)

Getting amped up for our trip... See you in La Paz soon, Steve.

|

|

|

|