David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65418

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

James O. Pattie, in 1824 (The Baja Portion)

[A fellow Nomad sent this to me, knowing my interest in mission history. The missions of Santa Catalina, San Vicente, Santo Tomás, San Miguel, and

the bay at Ensenada (Todos Santos) are mentioned. However, San Vicente is called Saint Sebastian?? This offers an intersting look at conditions at the

missions at that time.]

The Baja Portion... Taken from: https://user.xmission.com/~drudy/mtman/html/pattie/pattie.ht...

PATTIE'S PERSONAL NARRATIVE OF A VOYAGE TO THE PACIFIC AND IN MEXICO JUNE, 20, 1824 -- AUGUST 30, 1830

On the 28th, we travelled up this creek about three miles, and killed a deer, which much delighted our two Indian guides. At this point we encamped

for the night. Here are abundance of palm trees and live oaks and considerable of mascal. We remained until the 3d of March, when we marched up this

creek, which heads to the south, forming a low gap in the mountain. On the 7th, we arrived at the point, and found some of the Christian Indians from

the Mission of St. Catharine (Santa Catalina). They were roasting mascal and the tender inside heads of the [165] palm trees for

food, which, when prepared and cooked after their fashion, becomes a very agreeable food. From these Indians we learned that we were within four days'

travel of the mission mentioned above.

Here we concluded to discharge our guides, and travel into the settlement with the Christian Indians. We gave them each a blanket, and they started

back to their own people on the morning of the 8th. At the same time we commenced our journey with our new guides, and began to climb the mountain.

This is so exceedingly lofty, as to require two days' travel and a half to gain its summit. During this ascent, I severely bruised my heel. We none of

us wore any thing to shield our feet from the bare and sharp rocks, which composed almost the whole surface of this ascent, but thin deer skin

moccasins. Obliged to walk on tip toe, and in extreme anguish, the severe fatigue of scrambling up sharp stones was any thing, rather than agreeable.

But I summoned patience and courage to push on until the 12th. My leg then became so swollen and inflamed that it was out of my power to travel

farther. The pain was so severe as to create fever. I lay myself down on the side of a sharp rock, resigning myself to my fate, and determined to make

no effort to travel further, until I felt relieved. My companions all joined with my father, in encouraging me to rise, and make an effort to reach

the mission, which they represented to be but three miles distant. It was out of the question for me to think of it, and they concluded to go to the

settlement, and obtain a horse, and send out for me. I kindled me a fire, for I suffered severe chills. The Indians gave me the strictest caution

against allowing myself to go to sleep in their absence. The reason they assigned for their caution was a substantial one. The grizzly bear, they

said, was common on these mountains, and would attack and devour me, unless I kept on my guard. I paid little attention to their remarks at the time.

But when they were gone, and I was left alone, I examined the priming, and picked the flints of my gun and pistol. I then lay down and slept, until

sometime in the early part of the night, when [166] two Indians came out from the settlement, and informed me that the corporal of the guards at

St. Catharines wished me to come in. Being feverish, stiff, sore and withal testy, I gave them and their corporal no very civil

words. They said that the corporal only wanted me to come in, because he was afraid the grizzly bears would kill me. I asked them why they did not

bring a horse for me? They informed me, that the Mission had none at disposal at that time, but that they would carry me on their backs. So I was

obliged to avail myself of this strange conveyance, and mounted the back of one of them while the other carried my arms. In this way they carried me

in, where I found my companions in a guard house. I was ordered to enter with them by a swarthy looking fellow, who resembled a negro, rather than a

white.

I cannot describe the indignation I felt at this revolting breach of humanity to people in suffering, who had thrown themselves on the kindness and

protection of these Spaniards. We related the reasons why we had come in after this manner. We showed them our passport, which certified to them, that

we were neither robbers, murderers, nor spies. To all this their only reply was, how should they know whether we had come clandestinely, and with

improper views, or not? Against this question, proposed by such people, all reasonings were thrown away.— The cowardly and worthless are naturally

cruel. We were thrown completely in their power; and instead of that circumstance exciting any generous desires to console and relieve us, their only

study seemed to be to vex, degrade, and torment us.

Here we remained a week, living on corn mush, which we received once a day; when a guard of soldiers came to conduct us from this place. This mission

is situated in a valley, surrounded by high mountains, with beautiful streams of water flowing from them. The natives raise sufficient corn and wheat

to serve for the subsistence of the mission. The mission establishment is built in a quadrangular form; all the houses forming the quadrangle

contiguous to each other; and one of the angles is a large church, adjoining which are the habitations of [167] the priests; though at this time there

happened to be none belonging to this at home. The number of Indians belonging to the mission at this time, was about five hundred. They were

destitute of stock, on account of its having been plundered from them by the free, wild Indians of the desert. The air is very cool and temperate, and

hard frosts are not uncommon. This cool temperature of the atmosphere I suppose to be owing to the immediate proximity of the snowy mountains.

On the 18th, we started under the conduct of a file of soldiers, who led us two days' travel, over very high mountains, a south west course, to

another mission, called St. Sebastian (San Vicente?), situated near the sea coast, in a delightful valley, surrounded, like the

other, by lofty mountains, the sides of which present magnificent views of the ocean. This mission contains six hundred souls. This mission

establishment, though much richer and neater than the other, is, however, built on a precisely similar plan. Here they have rich vineyards, and raise

a great variety of the fruits of almost all climates. They also raise their own supplies of grain, and have a tolerable abundance of stock, both of

the larger and smaller kinds.

A serjeant has the whole military command. We found him of a dark and swarthy complexion, though a man of tolerable information. He seemed disposed to

conduct towards us with some courtesy and kindness. He saluted us with politeness, conducted us to the guard house, and begged us to content

ourselves, as well as we could, until he could make some more satisfactory arrangements for our comfort and convenience. To put him to the proof of

his professed kindness, we told him that we were very hungry. They soon had a poor steer killed, that reeled as it walked, and seemed sinking by

natural decay. A part of the blue flesh was put boiling in one pot, and a parcel of corn in the other. The whole process reminded me strongly of the

arrangements which we make in Kentucky, to prepare a mess for a diseased cow. When this famous feast was cooked, we were marched forth into the yard,

in great ceremony, to eat it. All the men, women and children clustered round us, and [168] stood staring at us while we were eating, as though they

had been at a menagerie to see some wild and unknown animals.— When we were fairly seated to our pots, and began to discuss the contents, disgusted

alike with the food, with them, and their behaviour, we could not forbear asking them whether they really took us to be human beings, or considered us

as brutes? They looked at each other a moment, as if to reflect and frame an answer, and then replied coolly enough, that not being Christians, they

considered us little superior to brutes. To this we replied, with a suitable mixture of indignation and scorn, that we considered ourselves better

Christians than they were, and that if they did not give us something to eat more befitting men, we would take our guns, live where we pleased, and

eat venison and other good things, where we chose. This was not mere bravado, for, to our astonishment, we were still in possession of our arms. We

had made no resistance to their treating us as prisoners, as we considered them nothing more than petty and ignorant officers, whom we supposed to

have conducted improperly, from being unacquainted with their duty. We were all confident, that as soon as intelligence of our arrival should reach

the commanding officer of this station, and how we had been detained, and treated as prisoners, we should not only be released from prison, but

recompensed for our detention.

This determination of ours appeared to alarm them. The information of our menaces, no doubt with their own comments, soon reached the serjeant. He

immediately came to see us, while we were yet at our pots, and enquired of us, what was our ground of complaint and dissatisfaction? We pointed to the

pots, and asked him if he thought such food becoming the laws of hospitality to such people? He stepped up to the pots, and turning over the contents,

and examining them with his fingers, enquired in an angry tone, who had served up such food to us? He added, that it was not fit to give a dog, and

that he would punish those who had procured it. He comforted us, by assuring us that we should have something fit to eat cooked for us. We immediately

returned quietly to the guard house. But a [169] short time ensued before he sent us a good dish of fat mutton, and some tortillas. This was precisely

the thing our appetites craved, and we were not long in making a hearty meal. After we had fed to our satisfaction, he came to visit us, and

interrogated us in what manner, and with what views we had visited the country? We went into clear, full and satisfactory details of information in

regard to every thing that could have any interest to him, as an officer; and told him that our object was to purchase horses, on which we might

return to our own country; and that we wished him to intercede in our behalf with the commander in chief, that we might have permission to purchase

horses and mules among them, for this purpose. He promised to do this, and returned to his apartment.

The amount of his promise was, that he would reflect upon the subject, and in the course of four days write to his commander, from whom he might

expect an answer in a fortnight.— When we sounded him as to the probability of such a request being granted, he answered with apparent conviction,

that he had no doubt that it would be in our favor. As our hopes were intensely fixed upon this issue, we awaited this answer with great anxiety. The

commander at this time was at the port of San Diego. During this period of our suspense, we had full liberty to hunt deer in the woods, and gather

honey from the blossoms of the Mascal, which grows plentifully on the sea shore. Every thing in this strange and charming country being new, we were

continually contemplating curiosities of every sort, which quieted our solicitude, and kept alive the interest of our attention.

We used to station ourselves on the high pinnacles of the cliffs, on which this vast sea pours its tides, and the retreating or advancing tide showed

us the strange sea monsters of that ocean, such as seals, sea otters, sea elephants, whales, sharks, sword fish, and various other unshapely sea

dwellers. Then we walked on the beach, and examined the infinite variety of sea shells, all new and strange to us.

Thus we amused ourselves, and strove to kill the time until the 20th, when the answer of the commander arrived, which [170] explained itself at once,

by a guard of soldiers, with orders to conduct us to the port of San Diego, where he then resided. We were ordered to be in immediate readiness to

start for that port. This gave us unmingled satisfaction, for we had an undoubting confidence, that when we should really have attained the presence

of an officer whom we supposed a gentleman, and acting independently of the authority of others, he would make no difficulty in granting a request so

reasonable as ours. We started on the 2d, guarded by sixteen soldiers and a corporal. They were all on horseback, and allowed us occasionally to ride,

when they saw us much fatigued. Our first day's journey was a north course, over very rough mountains, and yet, notwithstanding this, we made

twenty-five miles distance on our way.

At night we arrived at another mission, situated like the former, on a charming plain. The mission is called St. Thomas. These wise

and holy men mean to make sure of the rich and pleasant things of the earth, as well as the kingdom of heaven. They have large plantations, with

splendid orchards and vineyards. The priest who presides over this establishment, told me that he had a thousand Indians under his care. During every

week in the year, they kill thirty beeves for the subsistence of the mission. The hides and tallow they sell to vessels that visit their coast, in

exchange for such goods as they need.

On the following morning, we started early down this valley, which led us to the sea shore, along which we travelled the remainder of the day. This

beautiful plain skirts the sea shore, and extends back from it about four miles. This was literally covered with horses and cattle belonging to the

mission. The eye was lost beyond this handsome plain in contemplating an immeasurable range of mountains, which we were told thronged with wild horses

and cattle, which often descend from their mountains to the plains, and entice away the domesticated cattle with them. The wild oats and clover grow

spontaneously, and in great luxuriance, and were now knee high. In the evening we arrived at the port of Todos Santos, and there

passed the night. Early on the 23d, we marched on. This day we [171] travelled over some tracts that were very rough, and arrived at a

mission situated immediately on the sea board, called St. Michael. Like the rest, it was surrounded with splendid

orchards, vineyards and fields; and was, for soil, climate and position, all that could be wished. The old superintending priest of the establishment

showed himself very friendly, and equally inquisitive. He invited us to sup with him, an invitation we should not be very likely to refuse. We sat

down to a large table, elegantly furnished with various dishes of the country, all as usual highly seasoned. Above all, the supply of wines was

various and abundant. The priest said grace at the close, when fire and cigars were brought in by the attendants, and we began to smoke. We sat and

smoked, and drank wine, until 12 o'clock. The priest informed us that the population of his mission was twelve hundred souls, and the weekly

consumption, fifty beeves, and a corresponding amount of grain. The mission possessed three thousand head of domesticated and tamed horses and mules.

From the droves which I saw in the plains, I should not think this an extravagant estimation. In the morning he presented my father a saddle mule,

which he accepted, and we started.

This day's travel still carried us directly along the verge of the sea shore, and over a plain equally rich and beautiful with that of the preceding

day. We amused ourselves with noting the spouting of the huge whales, which seemed playing near the strand for our especial amusement. We saw other

marine animals and curiosities to keep our interest in the journey alive. In the evening we arrived at a Ranch, called Buenos Aguos, or Good Water,

where we encamped for the night.

We started early on the 25th, purchasing a sheep of a shepherd, for which we paid him a knife. At this Ranch they kept thirty thousand head of sheep,

belonging to the mission which we had left. We crossed a point of the mountain that made into the water's edge. On the opposite side of this mountain

was another Ranch, where we staid the night. This Ranch is for the purposes of herding horses and cattle, of which [172] they have vast numbers. On

the 26th, our plain lay outstretched before us as beautiful as ever. In the evening we came in sight of San Diego, the place where we

were bound. In this port was one merchant vessel, which we were told was from the United States, the ship Franklin, of Boston. We had then arrived

within about a league of the port. The corporal who had charge of us here, came and requested us to give up our arms, informing us, it was the

customary request to all strangers; and that it was expected that our arms would be deposited in the guard house before we could speak with the

commander, or general. We replied, that we were both able and disposed to carry our arms to the guard house ourselves, and deposite them there if such

was our pleasure, at our own choice. He replied that we could not be allowed to do this, for that we were considered as prisoners, and under his

charge; and that he should become responsible in his own person, if he should allow us to appear before the general, bearing our own arms. This he

spoke with a countenance of seriousness, which induced us to think that he desired no more in this request than the performance of his duty. We

therefore gave him up our rifles, not thinking that this was the last time we should have the pleasure of shouldering these trusty friends. Having

unburdened ourselves of our defence, we marched on again, and arrived, much fatigued, at the town at 3 o'clock in the evening. Our arms were stacked

on the side of the guard house, and we threw our fatigued bodies as near them as we could, on the ground.

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

Pattie

A good read - the snippet posted covers only a part of Pattie in Mexico.

Edited to say that Pattie again visited Mexico, but it was mainland and not Lower California.

There is another edition of the Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie, edited by Richard Batman (1988) that supplies chapter end notes throughout the

narrative.

Also Bruce Dinges (One-time director for publications in the Arizona Historical Society) has this to say about Pattie:

Heroism and adventure drip from the pages of Pattie’s story of his experiences, as told to Cincinnati magazine editor Timothy Flint, trapping beaver

along the Gila, exploring the lower Colorado River, fighting Indians and Mexicans, rescuing damsels in distress, and finally languishing in a

California prison. While scholars argue over the veracity of these hair-raising events and Pattie’s role in them, his rousing book still captures

readers’ imaginations with its vibrant description of the western wilderness viewed through the romantic lens of American expansionism.

[Edited on 11-28-2019 by John M]

|

|

|

Paco Facullo

Super Nomad

Posts: 1301

Registered: 1-21-2017

Location: Here now

Member Is Offline

Mood: Abiding ..........

|

|

Just leave me at St. Michael"s,,, I''ll be fine .......

arrived at a mission situated immediately on the sea board, called St. Michael.

Like the rest, it was surrounded with splendid orchards, vineyards and fields; and was, for soil, climate and position, all that could be wished. The

old superintending priest of the establishment showed himself very friendly, and equally inquisitive.

He invited us to sup with him, an invitation we should not be very likely to refuse. We sat down to a large table, elegantly furnished with various

dishes of the country, all as usual highly seasoned. Above all, the supply of wines was various and abundant.

The priest said grace at the close, when fire and cigars were brought in by the attendants, and we began to smoke. We sat and smoked, and drank wine,

until 12 o'clock.

Since I've given up all hope, I feel much better

|

|

|

LancairDriver

Super Nomad

Posts: 1603

Registered: 2-22-2008

Location: On the Road

Member Is Offline

|

|

X2! 😂

Quote: Originally posted by Paco Facullo  | Just leave me at St. Michael"s,,, I''ll be fine .......

arrived at a mission situated immediately on the sea board, called St. Michael.

Like the rest, it was surrounded with splendid orchards, vineyards and fields; and was, for soil, climate and position, all that could be wished. The

old superintending priest of the establishment showed himself very friendly, and equally inquisitive.

He invited us to sup with him, an invitation we should not be very likely to refuse. We sat down to a large table, elegantly furnished with various

dishes of the country, all as usual highly seasoned. Above all, the supply of wines was various and abundant.

The priest said grace at the close, when fire and cigars were brought in by the attendants, and we began to smoke. We sat and smoked, and drank wine,

until 12 o'clock. |

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

St. Michael

Note on page 152 (in Batman): San Miguel Arcangel, about thirty miles north of Ensenada and fifty miles south of San Diego.

Not a bad situation at the time.

JM

|

|

|

bajaric

Senior Nomad

Posts: 669

Registered: 2-2-2015

Member Is Offline

|

|

Describes the plain above Ensenada (de Todos Santos):

"On the following morning, we started early down this valley, which led us to the sea shore, along which we travelled the remainder of the day. This

beautiful plain skirts the sea shore, and extends back from it about four miles. This was literally covered with horses and cattle belonging to the

mission. The eye was lost beyond this handsome plain in contemplating an immeasurable range of mountains, which we were told thronged with wild horses

and cattle, which often descend from their mountains to the plains, and entice away the domesticated cattle with them. The wild oats and clover grow

spontaneously, and in great luxuriance, and were now knee high. In the evening we arrived at the port of Todos Santos, and there passed the night."

What a paradise it must have been. No pollution, wish I could go back in time and toss a lure off the beach.

One small error, the cattle grazing the grassland were owned by a man named Francisco Gastelum, not the missionaries. He had purchased 2500 hectares

of the land around what would become Ensenada from his father in law, the Jefe, who had been granted the land in 1804. At that time the land was

unoccupied and free for the taking, the indigenous people had been relocated to the mission at Santo Thomas where most of them eventually died. Happy

Thanksgiving! not so happy for the indigenous.

Gastelum, in a pattern that was repeated over and over in both Alta and Baja California grabbed the fast monehy and sold out to the Americans (The

International Company, in 1885) who proceeded to build the town of Ensenada.

[Edited on 11-28-2019 by bajaric]

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

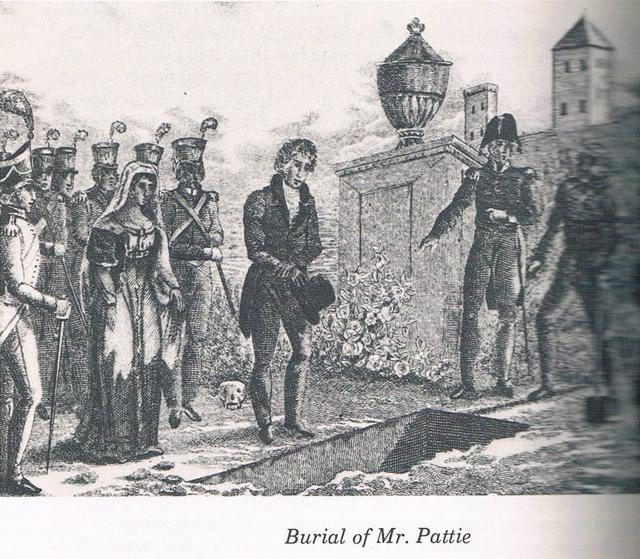

Pattie in prison in San Diego

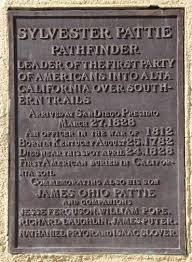

Mexican Governor Jose de Maria Echeandia had relocated himself from Monterrey to San Diego due to the better climate. Pattie, at San Diego, was

arrested as a Spanish spy and detained for almost a year. While James was imprisoned, his father Sylvester died in San Diego and was subsequently

buried. Sylvester is sometimes thought of as the first American to die in California. A plaque about this is at Presidio Park in San Diego.

Sketch showing James O. Pattie present at the burial of his father. Alongside James is a woman identified as "Miss Peaks" who had befriended James

while in prison.

James and the other trappers were eventually released with James likely returning to Kentucky where he is thought to have died.

Sketch from Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie, Richard Batman

[Edited on 11-28-2019 by John M]

|

|

|

BajaRat

Super Nomad

Posts: 1304

Registered: 3-2-2010

Location: SW Four Corners / Bahia Asuncion BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: Ready for some salt water with my Tecate

|

|

Good stuff, interesting read.

Thanks

|

|

|

caj13

Super Nomad

Posts: 1002

Registered: 8-1-2017

Member Is Offline

|

|

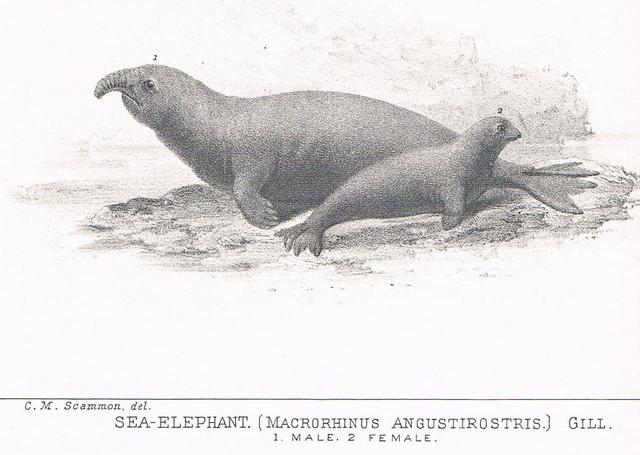

anyone know for sure what a sea elephant is? i assume its an elephant seal, but he specifically identifies seals separately, as well as whales, so

I'm just wondering?

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

Sea Elephant vs Elephant Seal

The facsimile edition of The Marine Mammals of the North-western Coast of North America and the American Whale Fishery by Charles M. Scammon (1874)

describes the sea elephant.

This is the Sea Elephant. Opposite page 117

Scammon writes: "Among the varieties of marine mammals which periodically resort to the land, no one attains such gigantic proportions as the Sea

Elephant. This animal which was sometimes called the Elephant Seal, and known to the old Californians as the Elefante marino..."

Scammon devotes eight pages to the Sea Elephant -

John M

[Edited on 11-29-2019 by John M]

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

Sylvester & James Pattie biographies

Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, Paul A. Tenkotte and James C. Claypool, University Press of Kentucky,2015, pp. 702-‘03

The below narratives are credited to Steven Pattie

Pattie, Sylvester (b. August 25, 1782, Craig’s Station, KY; d. May 24, 1828, San Diego, CA)

Sylvester Pattie, the son of John and Ann Pattie, led the first party of US citizens into Lower California. His parents had traveled overland from

Virginia to Kentucky in about 1781. They entered the state as part of Lewis Craig’s Traveling Church, a large Baptist fellowship from Spotsylvania

Co., VA, traveling west to escape religious persecution by the Anglican Church. Although the Patties were part of this caravan, they may or may not

have subscribed to the church’s religions views, since Craig welcomed all.

The migrating congregation established Craig’s Station in Kentucky (sometimes referred to as Burnt Station) in 1780-1781.

Sylvester Pattie grew up in Bracken Co., where his father, a veteran of the Revolutionary War helped establish the town of Augusta. He married Polly

Hubbard and they had eight children. After serving in the War of 1812, Sylvester Pattie moved from Kentucky to the Ozark Mountains of southern

Missouri. There he founded and ran a lumber mill, served on county commissions, and became relatively prosperous. However, his good fortune ended when

his wife died suddenly. His son James later reported that his father had been left “silent, dejected, and inattentive to business.”

Aware of the western migration of others, the 42-year-old Pattie decided to pack up and head west in 1825. He took with him his first-born child,

22-year-old James Ohio Pattie and dispersed the remaining children among his family. Other adventuresome individuals joined the Pattie Party, their

primary purpose being to trap and explore the west.

Pattie, his son, and the rest of their party were among the first to explore the US Southwest. Pattie led what was likely the first party of explorers

to see and to traverse the South Rim of the Grand Canyon (hence the naming of Pattie Butte). After four years of trapping and, at one point, working a

copper mine in what became New Mexico, they crossed the arid peninsula of Lower California and reached Mission Santa Catalina on the Pacific coast. [a

name transposition here].

Because they had trespassed onto Mexican territory, Mexican governor Jose Maria Echeandia took the party into custody on March 27, 1828. While

confined at the San Diego Presidio, Sylvester Pattie became seriously ill and died in May 1828. He was interred on the grounds of the Presidio and is

believed to be the first US citizen buried on California soil. A plaque mounted on the stone jailhouse immortalizes his contributions by referencing

the key role he played in the development of the American West: he was a “pathfinder, leader of the first party of Americans into Alta California

over southern trails.”

Sources:

Batman, Richard. American Ecclesiastes: An Epic Journey through the Early American West. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984.

“Kentuckians Early California Pioneers-Father and son, Bracken Co. Natives, Helped Open Up.” KP, June 21, 1931,8.

Pattie, James Ohio (b. 1803, Augusta, KY; d. circa 1833, place of death unknown).

James Ohio Pattie is the author of one of the most important early travel narratives in US literature, The Personal Narrative of James O. Pattie. He

and his father, Sylvester Pattie, were among the first pioneers in the US Southwest and California and are widely acknowledged to have led the first

party of explorers to thread the South Rim of the Grand Canyon and record that journey. Born in Augusta, KY, James Pattie was the oldest of the eight

children born to Sylvester and Polly Pattie. In 1812 his family moved from Kentucky to Missouri.

As noted by historian and Pattie scholar Richard Batman in his book American Ecclesiastes: An Epic Journey through the American West, Pattie’s

family prized education. Into his late teens, Pattie attended a school his grandfather helped found, Bracken Academy at Augusta, which later became

Augusta College. While not completely prepared for life as a fur trapper and explorer, this young frontiersman was uniquely positioned to record his

adventures.

The first published narrative recording an overland journey to California, Pattie’s story covers his sojourn of five years and several thousand

miles. From 1825 to 1830, his trapping and exploring led him, his father, and his companions through the Southwest, as they crossed the arid peninsula

of Lower California and eventually reached the Mission Santa Catalina on the Pacific coast. [already noted as the wrong designation].

Trespassing onto Mexican territory without passports, they were placed in custody and taken to San Diego, a Spanish settlement. Sylvester Pattie died

in jail and became the first US citizen buried in California, but eventually James Pattie was paroled. He traveled up and down the coast of California

for another year before sailing to Mexico in an attempt to secure reparations for furs lost before and during his and his father’s imprisonment in

San Diego.

After a half decade of exploration and fortune hunting, in 1830 Pattie arrived by ship in New Orleans, LA. By the time he finally returned to the

place of his birth on the Ohio River, he was physically and emotionally exhausted, not to mention penniless. He had only the stories recorded in his

journal.

Before long, word of Pattie’s western narrative reached Timothy Flint, a well-known preacher, author, publisher, and propagandist of American

Protestant expansion who lived in Cincinnati. He was fascinated by Pattie’s journey and set about making arrangements for publication of the

account. Ever since Pattie’s narrative first appeared in print in 1831, it has been in continuous publication. Some have argued that much of it was

invented and written by Flint himself-a viewpoint discredited by Pattie expert Batman. Based on a variety of compelling reasons, the narrative is

credited to the frontiersman rather than Flint’s imagination.

After his book was published, James Pattie vanished without a trace. The last record was his appearance on the Bracken Co. tax list in 1833. There

have been an abundance of theories and reported sightings over the ensuing years, but the most likely scenario is that he was a victim of the

wide-spread cholera epidemics that struck Kentucky in 1833 and was buried anonymously in a mass grave.

Sources:

Cleland, Robert Glass, and Glenn S. Dumke, ed From Wilderness to Empire: A History of California, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962.

Coblentz, Stanton A. The Swallowing Wilderness: The Life of a Frontiersman-James Ohio Pattie, New York: Thomas Yoseloff, 1961

Kentuckians Early California Pioneers-Father and Son, op. cit.,

Pattie, op. cit.

[Edited on 11-29-2019 by John M]

|

|

|

LancairDriver

Super Nomad

Posts: 1603

Registered: 2-22-2008

Location: On the Road

Member Is Offline

|

|

Thanks for this post John. After having read James Patties original account of their expedition, I was wondering where he gained his obvious literary

skills while at the same time being comfortable in the wild lifestyle. His family obviously valued education as noted. His narrative skill is not

matched among many present day authors or news people.

|

|

|

John M

Super Nomad

Posts: 1924

Registered: 9-3-2003

Location: California High Desert

Member Is Offline

|

|

A bit more on the accuracy of Pattie's writings

I was aware of some critics opinions of Pattie's writings. I read Pattie's book and didn't give a lot of consideration to whether or not he had all of

his facts straight. It was entertaining, and an adventure.

Then this topic popped up on Nomad and went back and re-read the Personal Narrative book. It's an easy read.

But I wanted to get a bit more info and do as many of us do - turn to the internet. I became aware of Richard Batman's American Ecclesiastes, the

stories of James Pattie. Don't have the book but a quick search found it for as little as $2.00 on the used book market. Still, I don't think I'm THAT

interested.

Then I came across a review of Batman's American Ecclesiastes book by Peter Wild. I know of Peter Wild and his studies of the Mojave Desert and in

particular the town of Daggett, Dix Van Dyke, and Mary Beal. So, thinking that another opinion of James Pattie's writing might be of interest to some,

here it is. This is likely my final post on this topic, think I've run it as far as I'm interested.

John M - see below.

Journal of Arizona History

Vol. 26 No. 3

Autumn, 1985

Review by Peter Wild, University of Arizona of: American Ecclesiastes: The Stories of James Pattie

James Ohio Pattie stands large in the early history of the Southwest. Trapping beaver westward along the Gila River in 1825, he and a small band of

adventurers probably became the first English speakers to enter the wilderness that is now Arizona. Over the next five years Pattie crisscrossed the

wild region, explored Northern Mexico, and got himself clapped into jail as a spy by a suspicious governor when he reached Mexican California.

Pattie’s Personal Narrative is a rollicking chronicle of his wanderings, sought out by historians, anthropologists, and botanists alike for the

glimpses it gives of life on the early frontier. Such enthusiasm has resulted in five major revivals of this book since its first publication in

1831.

For all that, many critics have not been especially kind to the young Missourian. None other than Hubert Howe Bancroft brands him “a self-conceited

and quick-tempered boy” who dashed off an “absurdly inaccurate” story. Other scholars have followed suit, doubting the “general readability

of the record” and at least once dubbing it “a melodrama.” Though readers keep coming back, often the more sophisticated among them can’t

bring themselves to swallow his tales whole.

Well, they might show caution. An inexperienced youth in his early twenties, Pattie poses as a stalwart leader of seasoned frontiersman. When it

comes time to rescue the sloe-eyed Jacova, it’s James who wins her heart after helping to free her from the Comanches. When his troupe is dropping

one by one in the sand on a desert crossing, it’s James who forges ahead to bring back succor to the dying. And so, it goes. Worse than that,

Pattie can keep neither his geography nor his dates straight. Some of his treks, for instance a foray of two thousand miles from the Southwest to the

northern Rockies, he renders with scrambled place names and/or a suspicious lack of detail. And his dates can be off by a year or more. Little wonder

that seasoned historians arch their brows over Pattie’s account.

We can thank the researches of Richard Batman for at last bringing order to this welter – not only order but a long-needed critical perspective. At

the outset, Batman reminds us of what should have tempered the judgments of carping critics over the decades. James Pattie is not writing history.

Rather, arriving penniless back in civilization, he is trying to recoup something from his five years of hardships by writing about them. Many a

disappointed westering man did as much. Few, despite equally absurd inaccuracies, succeed as well as does Pattie. He creates a chromatic yet sustained

tale wrought with passion, humor, and realistic detail that, whatever its faults, keeps readers in the twentieth century on the edges of their chairs.

With that established from the beginning, Batman launches into his main task: to separate fact from fiction in the Personal Narrative. He does this by

a monumental sifting of official records of the day, both American and Mexican; by keenly measuring Pattie’s “facts” against contemporary

accounts of the events; and by drawing on his own background in the region’s history to make judicious guesses when all else fails.

It turns out that raconteur Pattie indeed elaborates freely, placing himself at center stage when factually he has no business being there. As to the

winsome Jacova, Batman points to similar rescue legends then current along the Mexican frontier. Here as elsewhere, Pattie turns the tales he hears to

his own ends. And when he claims that after his release from the California prison, he combated a small pox epidemic by single-handedly vaccinating

twenty-two thousand people, Batman chuckles that the figure is more than the area’s total population at the time. Smallpox did sweep California in

1828, and vaccination did take place. But more than likely our self-appointed hero played little, if any, part in the events. In such ways, Pattie

rearranges rather than manufacturers his materials.

Yet even if we strip the Personal Narrative of suspect passages, we are left with a historically useful skeleton. Batman unearth correspondence from

Secretary of State Martin Van Buren corroborating Pattie’s stay in the calaboose, and he concludes that the released prisoner offers reliable

pictures of the California countryside. Further, Batman nails sown the issue of Pattie’s background and education, which in turn have everything to

do with the narrative’s general validity. In the past, some scholars have argued hotly that a publisher with an eye for sales buttonholed the

unlettered frontiersman and cast his tales into their dramatic shape. Not so, says Batman. Quite likely, Pattie was more literate than most men of his

times, and Batman backs this up with evidence based on admirable research.

American Ecclesiastes is a ringing title, but its author doesn’t make clear why it should apply to this chronicle any more than to others of its

kind. Also, I wish that while filling us in so well on other aspects of the Personal Narrative Batman delved more into the flora and fauna which

Pattie sometimes whimsically but misleadingly describes. And the general reader would benefit from more background on the political situation in

Mexico bearing on the changing fortunes of American trappers in the Southwest. But these are minor complaints concerning the first landmark study of

Pattie’s remarkable story.

[Edited on 11-29-2019 by John M]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65418

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Just arrived!

Thank you to the Nomad who sent this to me!

|

|

|

|