North America - Mexico

[For this issue of the newsletter we have received two interesting notes concerning the northernmost

distribution of American crocodiles along the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Editors.]

------------------------------------------------------

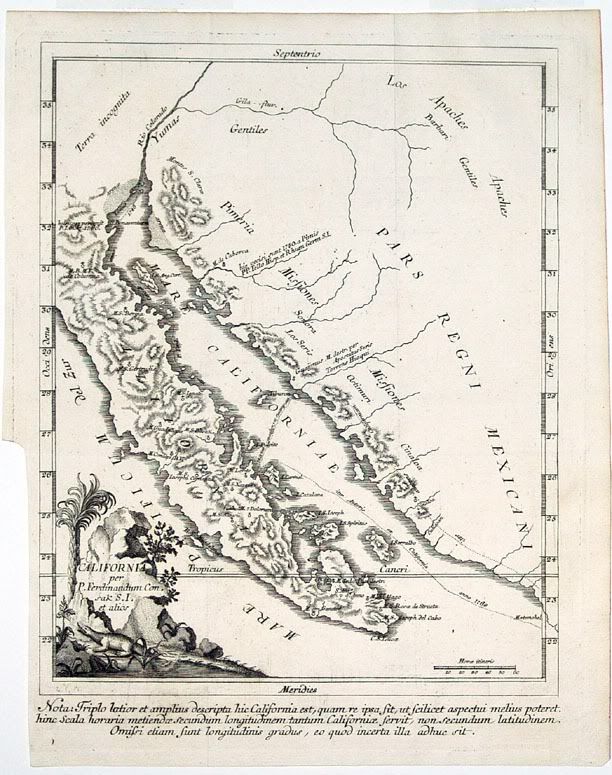

CROCODILIAN REMAINS FROM THE LATE PLEISTOCENE OF NORTHEASTERN SONORA, MEXICO. The fossil record of crocodilians in Mexico during the

Pleistocene is exceedingly rare. Of interest to us is a fossil-rich deposit from along the Río de Moctezuma, in mountainous, northeastern Sonora (29º

45.N lat., 109º 40.W long., 605 m elev.). Today the locality is dominated by a Sinaloan thornscrub community. The Río de Moctezuma begins just north

of the town of Nacozari and flows south to join the Río de Bavispe and the Río Yaqui, which then empties into the Gulf of California immediately south

of Guaymas, Sonora (Figure 1). The fossil lake deposit is situated adjacent to the village of San Clamente de Térapa, about 10 km south of Moctezuma.

To date, our work has concentrated on surface exposed fossils, and has already produced 39 vertebrate taxa. The precise age has not been

established, but based on the recovery of the bison, it is likely to be within the past 500,000 years. During this time a lava-dammed Río de

Moctezuma produced a short-lived lake (Lago Térapa, Lake Terapa). Fossils are recovered from the three sedimentary units of the lake deposit. The

structure of the sediments, their distribution within the basin, and the nature of the fauna indicate the occurrence of a shallow paludal (marsh or

swamp) environment, which we believe to be similar in structure to the llanos and pantanal (flooded grasslands and savannas) of South America. Areas

within the Lago Térapa basin during this phase contain the tropical rodent, Hydrochaeris (capybara), along with grassland species such as

Bison (bison), Equus (horse), Glyptotherium (glyptodon), and Holmesina (extinct giant armadillo, pampathere).

A sedimentary facies contains well-sorted, coarse- to fine-grained sands and is consistent with a slow-flowing river channel within the paludal

environment. This facies contains crocodilian teeth, snails, clams, and abundant fish and turtles. Other areas within the basin

during this phase appear to lack what we interpret to be open water and contain remains of turtles, large tortoise, horse, deer, extinct pronghorn,

xenarthrans (ground sloths and armadillos), and tropical birds (possibly representing near-shore and less submerged grasslands).

Six isolate teeth recovered from riverine facies sands are distinctive to those found in crocodilians, and their sizes are indicative

of at least two different life stages. The teeth are conical and pointed to blunt-pointed; two of the teeth are slightly recurved (Figure 2). All the

teeth have distinct vertical striations on the surfaces of the crown (a characteristic found on both crocodylids and alligatorids).

Most of the teeth are weakly to strongly carinate (keeled) with crests oriented postero-mesially.

No crocodilians live today in interior northern Mexico or in the greater Gulf of California along the mainland or Baja California.

Crocodylus acutus (American crocodile, cocodrilo del río) is the most widely distributed of the North American crocodiles. Its present

distribution includes Altata (near Culiacán) and Mazatlán within the entrance to the Gulf of California (Ernst et al. 1999). Seri (Comcáac) Indians

report the occasional sightings of a crocodile ("gila monster from the sea"; assumed to be C. acutus) as far north as Punta Sargento

(the northernmost mangrove lagoon on the Sonoran coast), including two sightings recorded during the 1900s, with one large adult washed up on the

southeast shores of Tiburón Island (Nabhan, in press; Figure 1). Baegert (1952) indicated seeing "alligators" of considerable size

at the confluence of the Colorado River and the Gulf in A.D. 1751.

These northern reports likely represent vagrant, range-exploring individuals and are recorded only along coastal waters and near-shore islands. We are

not aware of any oral accounts or published literature indicating subfossil or historic records of any crocodilian being observed

up-river from the Gulf of California in Sonora. Recent damming of major rivers (e.g., Río Mayo and Río Yaqui) for water storage and hydroelectric uses

have all but completely decimated the coastal mangrove lagoons, removing these northern disjunct communities and thereby restricting the

crocodile to the tropical south.

This tropical and mangrove lagoon species is distinctive to coastal brackish and freshwater habitats, though it is known to travel up major river

systems (which is what we suggest to explain the arrival of a crocodilian at Lago Térapa; 350 km inland during the Ice Age). The

alligatorid, Caiman crocodilus (common caiman) is a small, highly adaptable crocodilian that lives among other areas,

along the Pacific Ocean coast of southernmost Mexico and Central America the only other crocodilian today on the Pacific Ocean side of

Mexico.

Reports of crocodilian fossils from the Ice Age of Mexico are rare in the literature. Two fragmented jaws, isolate teeth, a

vertebra, and dermal scutes (osteoderms) recovered from the late Pliocene deposits of Las Tunas (> 2.0 million years ago) on southernmost Baja

California were attributed to cf. Crocodylus moreletii (Morelet.s crocodile; Miller, 1980). No verified accounts exist for natural C.

moreletii population along coastal, western Mexico. These Pliocene-Age fossils warrant a new examination based on the identification and present

distribution of that species. We suggest that the crocodilian at Lago Térapa was likely.

We thank the personnel of the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo (Ohio) for their donation of the skeleton of Dreadnought, a 4.3 m long, +44 year old male

Crocodylus acutus. Such material for our comparative skeleton collection is critical to the teaching and researching of fossil crocodilians.

Jim I. Mead, Dept. of Geology & Quaternary Sciences Program, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011- 4099, USA

<James.Mead@nau.edu> & Arturo Baez, Dept. of Geosciences & College of Agriculture & Life Sciences, University of Arizona, 4101 N.

Campbell Ave., Tucson, AZ 85719, USA.

=======================

CROCODYLUS ACUTUS IN SONORA, MEXICO. The American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) is a widely distributed species, ranging

from northern South America to the tip of the Florida peninsula and the Pacific coast of Mexico. In the latter, the mouth of the El Fuerte River (25º

49. N, 109º 24. W), in the state of Sinaloa, is considered its northernmost stronghold. However, there are historical accounts of American

crocodile populations farther north in Sonora state, such as the report by Jesuit Father Juan Nentuig, who in 1764 wrote about

crocodiles in the mouth of the Yaqui River (27º 21. N, 110º 30. W). Today, that area is much changed: as one of Mexico.s biggest and

most productive agricultural valleys, the river’s freshwater flow has been reduced to such an extent that crocodiles are no longer found

there. The same could be said of the mouth of the Mayo River, some 100 km to the southeast and where long-time residents still remember the

caimanes.

Occasional individuals may have wandered away from those areas, as suggested by the capture of a crocodile on 19 January 1973 in the

El Ciego estuary, near Las Guásimas, approximately 30 km east of Guaymas, Sonora (27º 52. N, 110º 33. W). This specimen was netted unintentionally by

two fishermen who were night-fishing for sea bass. From the photo published in El Diario newspaper the following day, the crocodile

was estimated to measure approximately 2.5 m. Because that area does not have freshwater discharges, is located at the southern fringe of the

Sonoran Desert, and receives irregular and scarce rainfall, it is unlikely that a breeding population of American crocodiles was ever

established there. The surprise and interest that the event caused among local people is evidence that the species was not common then in the area. It

may constitute the northernmost recorded evidence of the species along the Pacific coast. Today, it appears that the species has been extirpated from

Sonora. Carlos J. Navarro, Marine Biologist & Wildlife Photographer, Mexico<navarrosc@hotmail.com>.

|