| Quote: | Originally posted by TW

DK when you've been at the mission did you ever see any remains of the trail leading out to hwy 1 near San Ignacito? |

No Tom, but that trail goes through a pass/ canyon that comes into the Santa Maria mission valley a mile past the mission... where the road drops into

the white sand arroyo...

Norm Christie ('rockman' on Nomad) wrote an article about hiking to the mission on that trail, then down the canyon to Punta Final... I have a link to

that story in my web site...

It is from 1993:

========================================================

BACKPACKING

Mision Santa Maria

By Norm Christie

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

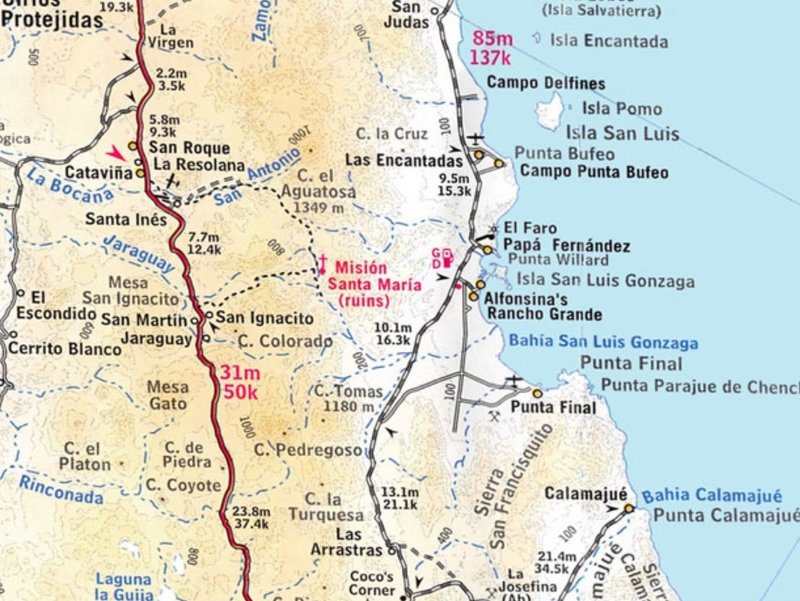

The ruins of Mision Santa Maria de Los Angeles are about as far from a road as any mission on the Baja California peninsula. I had tried for two years

to mobilize some friends for a backpacking trip into the site without success. So, in mid-September 1993, when "Dr. Bob" Binton phoned me to say that

he had three friends wanting to make the hike in October, I enthusiastically accepted his invitation. We rendezvoused near Catavina on the eighteenth

of October. During the next five days we experienced some of the most fascinating and beautiful areas on the peninsula.

The Santa Maria mission was the last mission built by the Jesuits before they were expelled from Mexico for political intrigues. The area, which

includes freshwater springs in a valley named "Cabujacaamang" by the Indians, was first seen by Father Fernando Consag in 1746, when he discovered

Bahia San Luis Gonzaga on the Sea of Cortez. The mission itself was built in 1767 by Father Arnes and Diez as the third in a string of remote

missions. It was designed to replace Mision Calamajue which was built in the previous year, but was found to have water that was too highly

mineralized to sustain crops.

Although built in a wide canyon surrounded by volcanic rock and granite, Mision Santa Maria was the only mission built by the Jesuits mainly of adobe

bricks rather than stone. After the Jesuits reluctantly departed from Baja Sur, the Franciscans occupied the site for a few months in 1768, but

abandoned it as a principle mission when they began construction of the new Mission San Fernando de Velicata, forty miles to the northwest, in 1769.

At that time, the Santa Maria mission became an outpost of Mission San Francisco Borja until 1818 when it was permanently abandoned.

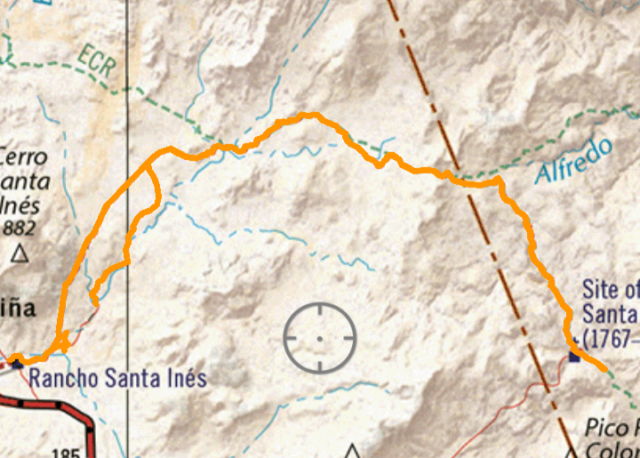

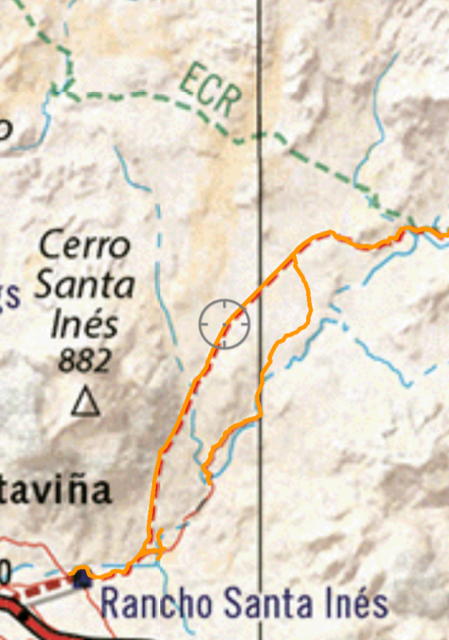

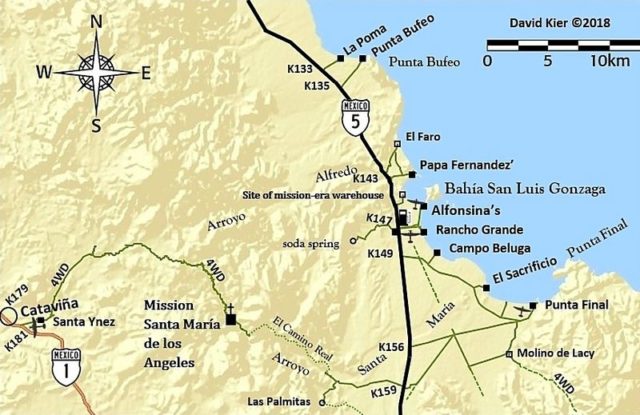

Beginning in 1961, attempts were made to bulldoze a trail from Rancho Santa Ines, past the Santa Maria mission to Bahia Gonzaga on the Sea of Cortez.

Constructed with great amounts of effort, the road reached a point about a half mile east of the mission on the Camino Real, but was abandoned because

of impassable terrain. Today that trail has eroded and is obliterated in many areas, but is still the most common route for Santa Maria's infrequent

visitors.

Our group decided on a different route. Our starting point was the small "Chelanga" gold mine just north of Jaraguay, reached by a dirt road turning

off the highway at km 187. Our route was northward, crossing the peninsula divide at Puerto la Mission (elevation 2500). We passed grinding stones,

sleep circles and other evidence of early Indians. The rock in this are is mainly volcanic. As we proceeded northward, we dropped down into a dry wash

which had eroded into the light colored granite under the volcanics. We encountered our first waterholes about one mile past the divide. Many maps

identify this canyon as Canon Santa Maria, but in fact, this canyon runs into the real Canon Santa Maria (as identified by the locals and historians)

about a mile below the mission. We continued northeast in this canyon. Occasional pools of water developed into a continuous small stream which

occasionally blossomed into large pools surrounded by forests of palm trees. This water is present throughout the entire year. I used a filter before

drinking the water, but "Tomas" Campbell, a fellow hiker, took his chances and drank the the water straight from the stream during the entire trip

without ill effects. A few wild mountain sheep, deer and smaller wild animals inhabit this area, but free-range cattle very rarely get up into this

remote yet enticing region.

There are two main types of palm tree here; Palma Verde (Palma Almenico) and Palma Azul (Palma Senico and Palma Taco). Both bear small edible fruits

which taste, as one might imagine, like dates. They add a gourmet touch when pitted and added to instant Quaker Oats in the mornings.

Our first night's campsite was in the canyon northwest of Pico Colorado at an elevation of about 1600 feet. The next morning, Wednesday, we explored

some tributary canyons in the area and then departed the campsite at 11:30 AM. Hiking over the smoothly eroded granite boulders in the steep sided

canyon, we arrived at the junction of this canyon and the main Santa Maria canyon at 2:15 PM. We had been told that the best campsite in the area was

about 1/4 mile downstream in an oasis-like setting with a large pool. The Santa Maria mission is about one mile upstream from the junction.

The following morning, leaving our sleeping bags and camp gear at the oasis, we hiked up the broad main canyon (the real Canon Santa Maria), to the

mission. I had read that the mission had been built of stone blocks and adobe, but there was no evidence of stone blocks anywhere. The site originally

consisted of a large adove church building, and adobe barracks-like quarters and storage building, and a stone corral. Aerial photos show evidence of

other buildings that were probably made of palm wood, but it is not evident on the ground. A photo published in 1908 shows the church walls to be much

higher than they are now, and the storage/barracks building to be nearly intact (though roofless). Today, a few pits are evident where treasure

hunters may or may not have found the legendary lost treasure of the Jesuits. A small trickle of running water nourishes a glassy palm forest along

the watercourse, but there are no deep pools remaining near the mission. Remnants of a crude aqueduct may still be seen.

The mission had attracted more than 300 Indians when the cadre of newly arrived Franciscans moved north ward in 1768. Although there was sufficient

water here, there was insufficient arable soil to grow the corp needed to keep the Indians attracted to the church.

The following morning, we split up and explored various tributary canyons. We were mainly searching for rock art and pictographs which had been

reported in the area. No significant art was found that day, but some garnet crystals were discovered in quartz veins in Cerro Pinto canyon, south of

the main canyon. This canyon has running water (sometimes underground) and several large, deep water holes.

On the morning of October 20, we cleaned our campsite and packed up for the last leg of our hike toward Bahia Gonzaga. Our local guide, Prieto, told

us that the main canyon downstream had several impassable areas of deep pools flanked by vertical smooth awls of granite, so we hiked up above the

canyon, on its north rim, along the remnant of the old Camino Real. This involved climbing slightly to a maximum elevation of 1375 feet (the west end

of the bulldozed trail) and proceeding for about a half mile. Along this stretch we observed several rocks with petroglyphs. We then returned to the

floor of the canyon (675 feet) where there was still water. As we proceeded westward, the canyon became wilder and sandier. Reaching the beginning of

the large alluvial fan at about 575 feet elevation, there was no sign of surface water; it was now flowing under the sand. We walked about another

mile before arriving at our previously arranged meeting site with a couple of vehicles (with ice chests full of notably cool refreshments) and

proceeded on wheels to Punta Final where resident friends were preparing a welcome back dinner.

We were all tired, but not exhausted. Although we did not have a thermometer, temperatures were estimated to range from about 85F during the day to

55F at night. I had made the mistake of wearing light weight hiking boots. They began to fall apart while we crossed the sharp stones of the volcanic

terrain on the first day. Temporary repairs were made with an awl and some cord, but I suggest that future hikers in this area wear stronger boots. On

our final evening, the boots, our only casualty, were cremated and given a decent burial.

Getting there: The turnoff to our trailhead at the Chelanga mine is 6.5 miles south of Catavina on Highway 1. Catavina is 295 miles south of Tijuana,

and the location of a nice La Pinto hotel, gas station (with mechanics) and a great little cafe at the station. More elegant meals (and margaritas)

are available at the hotel. An alternate trailhead or exit point is Rancho Santa Inex, on a signed, paved side road 1/2 mile south of Catavina. Here

there is a Flying Samaritans medical clinic, paved runway, and a cafe where you can get cool drinks and information. The terminal point for our hike

is near the coastal gravel road from Puertocitos to Highway 1 at Laguna Chapala. This road is good from Alfonsina's southward, but terrible between

Puertocitos and Alfonsina's. Ice, drinking water and a good dirt airstrip are available at the turnoff to Alfonsina's. On this route, the last

dependable gas and supplies are at San Felipe, 155 miles south of Mexicali.

Climate: Because summer temperatures often exceed 100 degrees, this trip would be very uncomfortable from July through September. December through

March can be cold, sometimes in the 40's at night. Rain is rare, but drizzle is possible in the winter, and tropical downpours occur occsionally in

summer.

Recommended Supplies and Equipment: In addition to common backpacking equipment, the following items should be emphasized. Sturdy boots, topo map and

altimeter, water purifier, star chart (incredibly clear sky), sun screen, sunglasses, tweezers and antiseptic (for cactus pines), Mexican insurance

for your vehicle.

Dangers and Annoyances: If rain is observed or seems likely, do not camp in the canyon bottoms; flash floods can be killer in this region. Although we

saw none on our trip, rattlesnakes and scorpions do exist in all parts of Baja. These creatures are mainly nocturnal, so watch where you put your

hands and feet at night. We experienced no insect pests, but flies and gnats can be abundant after rain. Although the Mexican government tries to keep

the roads in good order, Highway 1 is about one foot per lane narrower than US. roads, has heavy bus and truck traffic, has no shoulders and drivers

may suddenly come up on potholes and cattle. Driving at night is not recommended, especially for newcomers to Baja.

[Edited on 11-11-2022 by David K] |