Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Old Place Names on Google Earth

On Google Earth there are place names that do not appear on modern maps but can be found on antique maps. They always appear in the wrong place.

Does anybody know the story behind the appearance of these names?

Here are the examples I know about, Does anyone have any others?

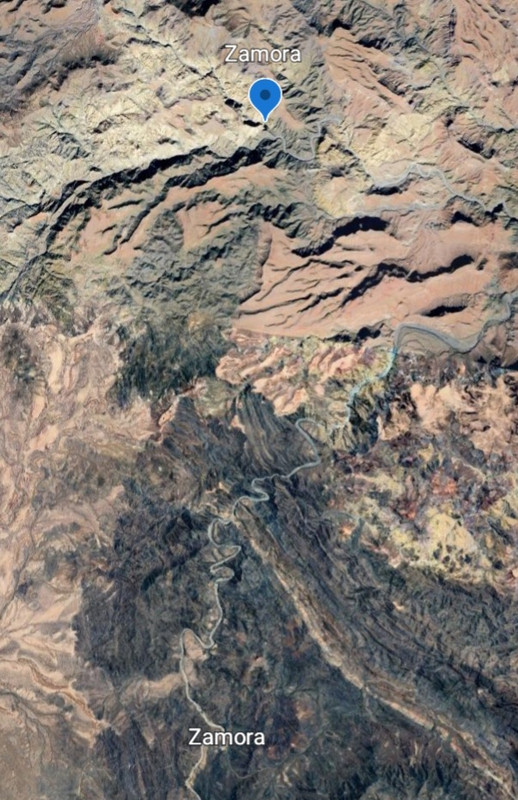

Zamora

Santa Ana

Catarina

Agua Leon

Los Sauces

[Edited on 8-25-2025 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

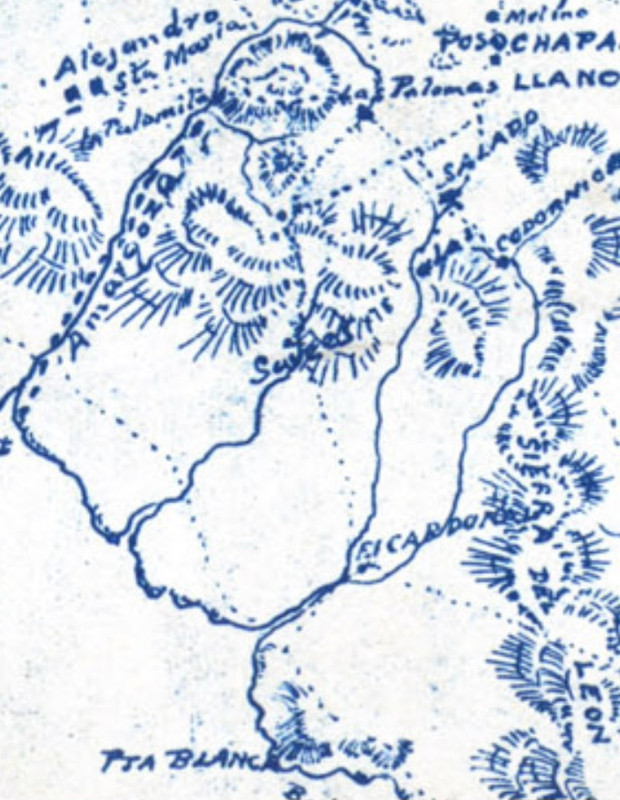

Los Sauces (Sauces) on Golbaum. In the center of the image.

GE 29°14'27"N 114°40'39"W

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Thank you for your post, Lance.

I don't have a lot to contribute but hope other Nomads get involved (4x4abc, geoffff, etc.)!

1) Zamora on the Mexican topos is an error, as far as the arroyo name. They labeled Arroyo El Volcán as Arroyo Zamora and the true Arroyo Zamora

(just to the south) as Arroyo El Volcán. I corrected that on the Benchmark Baja California Atlas, pre-publication.

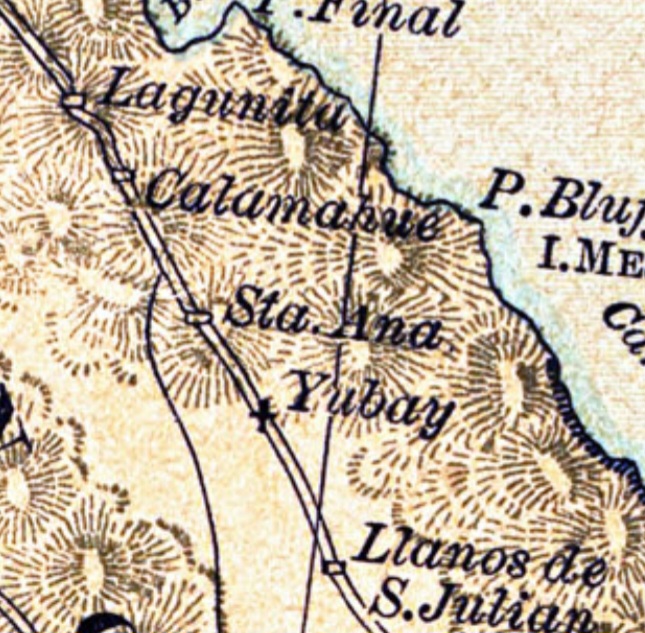

2) Santa Ana was a visita of Mission San Borja and today is a ranch with a little oasis. Oddly, the Santa Ana you show is also on old maps northwest

of San Borja, closer to Tinaja de Yubay.

Here it is on an 1860s map, on El Camino Real, between Yubay and Calamajué: https://vivabaja.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/1860s-Baja-M...

also on this 1884 map: https://octopup.org/img/media/maps/baja/1884--Baja-Californi...

Not sure about why your images have the names in two places (one with a dart)??

Again, thanks for your interesting post... Nomad was getting pretty stale!

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Thanks David!

The locations with the darts are the actual locations VS the Google Earth name placement.

The Santa Ana shown is the ranch that was apparently founded at the original Agua de Higuera, now called Aguajito.That means the Santa Anas on the old

maps you linked are actually Agua de Higuera. I will see if I can link that thread.

[Edited on 8-26-2025 by Lance S.]

[Edited on 8-26-2025 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

BajaNomad - 1860s Baja California Map Chat - Powered by XMB https://share.google/x4PTW61ikssFA5zm9

[Edited on 8-26-2025 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Some later maps called the desert around El Crucero/Punta Prieta the 'Llanos de Santa Ana'

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

That 'Lagunitu' on the El Camino Real... could be either San Francisquito (1 km north of the new Coco's Corner/ Las Arrastras) or Las Palmitas... iI

would guess??? They are the only two springs in that section (Calamajué to Santa María).

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

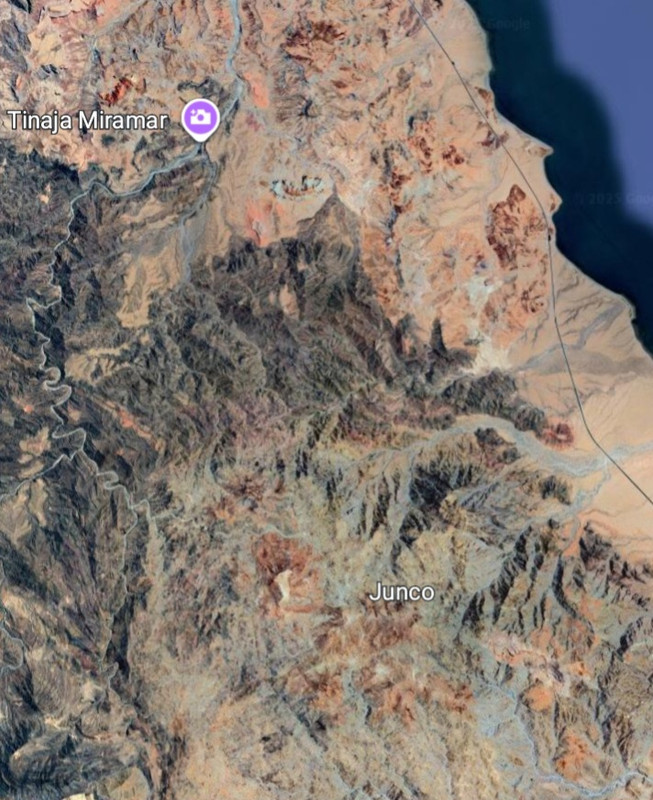

Anybody have a location for a water source called Junco?

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4455

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

old maps are notoriously inaccurate

it is a frustrating multi day endeavour to consolidate today's accurate satellite maps with wild scribbles of the Baja past

I have given up on many

the first maps that align with current data are the Gulick maps

here is an interesting historical fact - the historic Spanish invaders were not able to draw maps

that is why we don't have a single map of Baja depicting Camino Real

however, the indigenous people of mainland Mexico were great map makers

from there we have the only maps outlining "Camino Real"

one of my quest has been to locate a road between La Paz and El Triunfo in the 1800's

La Paz as the administrative and shipping center of southern Baja and El Triunfo as the rich mining community

so far - nada!

and nothing on the ground that would qualify as an old road

no personal recollection either as nobody from the 1860's is alive

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

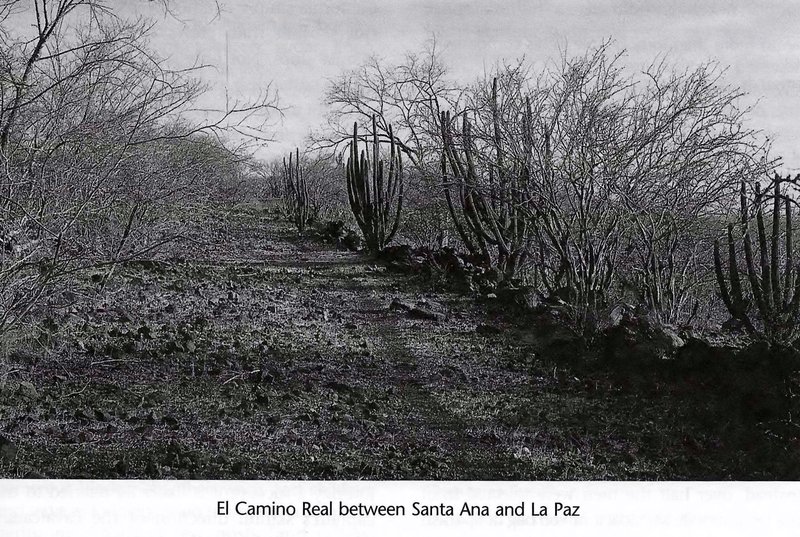

Harald, in Harry Crosby's book (Gateway to Alta California) is his photo of the Camino Real south of La Paz.

As for maps that show the Camino Real in the Californias, see the 1787 map. Not any kind of detail at that scale, but shows the existence of it. Maps

all at www.vivabaja.com/maps

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4455

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by David K  | Harald, in Harry Crosby's book (Gateway to Alta California) is his photo of the Camino Real south of La Paz.

As for maps that show the Camino Real in the Californias, see the 1787 map. Not any kind of detail at that scale, but shows the existence of it. Maps

all at www.vivabaja.com/maps |

Crosby's image is a mining road

there is no map of Baja California where is says on the map "Camino Real"

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by 4x4abc  | Quote: Originally posted by David K  | Harald, in Harry Crosby's book (Gateway to Alta California) is his photo of the Camino Real south of La Paz.

As for maps that show the Camino Real in the Californias, see the 1787 map. Not any kind of detail at that scale, but shows the existence of it. Maps

all at www.vivabaja.com/maps |

Crosby's image is a mining road

there is no map of Baja California where is says on the map "Camino Real" |

I thought you said shows the Camino Real. Right, they typically don't label road names, just mission names.

As for proof the mission road in Baja was indeed an El Camino Real, Crosby provides the proof: in the 4th paragraph, reproduced below...

Chronicled by the Father Miguel Venegas of the Same Society of Jesus. This Historical Account was completed on the Seventh of November of

1739.

Book X

Chapter 22: “Concerning the great extent to which the Missionary Fathers have labored in opening roads throughout the whole region.”

It is this impossibility which the missionaries have surmounted by dint of their personal labor, the aid of the Indians already converted and

civilized and the assistance of the soldiers. In order that the work might be fairly distributed among all the Indians, in proportion to the advantage

which they would derive from the building of these roads, the fathers adhered to the following plan in making this distribution. First of all, they

had a main highway camino real built through the center of the mission district extending through its entire area and running

lengthwise from south to north. All the rancherias belonging to the mission worked together in building this road, for it was of common advantage to

them all. Then each rancheria assumed the responsibility for building a special road leading from its settlement and joining the camino

real which was, so to speak, the main trunk-line in which all the separate roads from the rancherias terminated. By this means connection was

finally made with the headquarters of the mission.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Page 19 of 'Gateway to Alta California' (Harry Crosby ©2003)

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4455

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

23.762026°, -110.073309°

[Edited on 8-27-2025 by 4x4abc]

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

I thought you had seen it!

Now, does any part of it go in a straight line towards Todos Santos from La Paz or is this after the junction towards Real de Santa Ana/ Santiago?

If you are sure it a post-mission mine road, and not to the Santa Ana mines, what mine?

Thank you!

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4455

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by David K  | I thought you had seen it!

Now, does any part of it go in a straight line towards Todos Santos from La Paz or is this after the junction towards Real de Santa Ana/ Santiago?

If you are sure it a post-mission mine road, and not to the Santa Ana mines, what mine?

Thank you! |

the images are part of the 1860's mining road network between Las Gallinas and Santa Ana

however, 100 years earlier Camino Real used the same route between La Paz and Santiago through Santa Ana.

Camino Real did not run in straight lines - it has twists and turns like any good hiking trail

there is no detectable section of Camino Real between La Paz and Todos Santos.

between La Paz and San Jose are several well preserved sections in the Sierra La Victoria

Mining, agriculture and ranch operations have covered most of Camino Real south of la Paz

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4455

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

it took me a long time to locate maps of New Spain that depicted Camino Real and said so as well in writing

turns out the Spaniards were not capable of making maps

but the indigenes had a long tradition of depicting their environment

so, early maps of New Spain were drawn by locals and then the Spaniards would write comments onto the maps (locals had not learned yet how to read and

write)

trails would always have footprints in them to distinguish them from other linear structures like walls

so here is a rare example of Camino Real on a historic map.

The text that came with the map:

"During the pre-Hispanic period, indigenous peoples developed a pictographic writing system that used images and symbols to express ideas in their

codices and documents. After the Conquest, these scribes learned alphabetic writing, often in schools run by Catholic missionaries. On their maps,

they combined pictograms with alphabetic words, as can be seen in the work shown here.

Most maps dating from the 16th and early 17th centuries were created to document mercedes (grants of land). The Spanish realized the importance of

pictographic documents to indigenous peoples. When a grant of uninhabited land was made, local Spanish authorities, often a corregidor, were asked to

send a painting as part of the documentation necessary to grant the grant. Since very few Spaniards could draw maps, it was the indigenous scribes who

fulfilled the requirement.

The process of reciprocity is evident in these maps. We can often see the work of an indigenous cartographer who communicated through pictographs and

images as the basis of the map; later, someone who knew Spanish completed the maps with text. For these indigenous people, showing the “sign” of

where everything began, their place of meaning, had special meaning; in the map of San Juan del Río we see the ceremonial center, called “these are

cues,” well defined and ornamented, which is today the Barrio de la Cruz and the archaeological zone.

- Map typologies

Most of the maps from the 16th and 17th centuries were prepared to be delivered to the viceregal government, along with other documents as part of the

process to grant a grant. One of the requirements to receive this grant was that such lands were at an officially established distance (approximately

two kilometers) from cultivated fields and other properties, so that they would not cause harm to third parties in dispute, such as other owners or an

adjacent indigenous community. On the map of San Juan del Río, the land transfer is requested by Don Pedro de Quezada (at the end of the 16th century

he was the richest farmer in all of Querétaro, his fortune came from his wife, Doña María de Jaramillo, who was the daughter of Juan Jaramillo and

Doña Marina –Malitzin-) to obtain a place to sell, the map indicates: “this is the place that is requested” (in the case of the sale or sale).

Note that there was already a “sale” on the outskirts of the town (lower left margin of the map) that belonged to Don Lucas Lara de Cervantes, to

whom the Mayorazgo de La Llave fell by inheritance, and that the one that was requested was already marked on the site before leaving the “fence”

on the edge of the Camino Real, in the vicinity of “las cavallerías”: “la vna caballería” and “la otra caballería”.

This map is signed by Fernando de Mujica, who certifies that "this painting is certain and true," who must have been a civil authority.

We appreciate that San Juan del Río was a fortified city, with a fence around it called on the map “the town fence” that served as a defense

against attacks by Chichimecas, as well as to prevent cattle from escaping; the cavalry fields were also marked on both sides of the Camino Real,

which is today Avenida Juárez.

- Reading and writing maps

On the map of San Juan del Río, images, symbols and words appear intermingled, which represent spatial extensions of the land. Hills and mountains

were features of the landscape, as well as sacred sites for many indigenous peoples, which stands out on this map as the “Texco hill” today Cerro

de La Venta.

Especially important are the rivers, whose life is reflected in the water that nourished the crops; these were frequently represented with blue bands

indicating an interior pattern of currents and whirlpools. Sometimes the banks of the rivers were decorated with a double circle in the shape of a

doughnut, which represented jade for pre-Hispanic artists. While this way of depicting water may have been just a convention at the time of the

creation of these maps, its origin comes from an indigenous worldview. In central Mexico, the deity of rivers and streams was Chalchiuhtlicue, whose

name means “she with the jade skirt,” represented by the symbol of jade that borders the rivers.

We can see on the map the San Juan River, which gave its name to the town when it was founded by the Spanish, on the map it is described as “El Rio

Grande”; a river that crosses the town and from which “La acequia que ba por el pueblo” is taken, which was an aqueduct that was opened from the

river to supply the town and which meets it again, in the vicinity of what is now the Barrio del Espíritu Santo.

On the banks of both the river and the irrigation ditch, we can see the “milpas” (arranged in rectangles) and right in the middle of them we can

see what is now the Paso de los Guzmán, from the “fence” to the “Rio Grande”.

Other characteristic features of the indigenous maps can be seen, for example, in the paths marked by small footprints as if they had left a trail to

show the presence of people. We can see this on the Camino Real, which led to the interior of New Spain, which crosses the town from east to west, as

well as on two “streets” on either side of the temple of San Juan del Río. The cartographers created maps not only to record the territory, but

to leave testimony of the human acts that shaped the landscape.

- Current use

The maps of New Spain that we can see today were painted between the 16th and 18th centuries, and were accompanied by a file, as evidence for the

granting of land grants or ranches. Likewise, they were painted to prove the possession of lands by indigenous communities. These lands mostly

represented an ancestral legacy and the means of subsistence of the communities, and also allowed them to comply with the tributes established by the

crown.

The use that was given to them a few centuries ago has not changed much today, since the legal validity of the maps still persists, which is why for

these communities they continue to be of vital importance in land disputes, since in them you can see the location of cattle, mountains, bridges,

streams, rivers, among other elements, which allow to show the delimitation of the space between nearby populations. Likewise, these maps constitute

an invaluable legacy for the history of our country in pictographic terms, but above all they allow us to enter into the worldview of our ancestors;

and allows rural communities to continue their livelihood, in addition to providing them with elements of identity and belonging."

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

|