| Pages:

1

2

3

..

6 |

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

From Choral Pepper: The Lost Diaz Grave

Something to look for this winter???

THE MYSTERY OF DIAZ' GRAVE by Choral Pepper

Another chapter from Choral's manuscript 'Baja: Missions Mysteries, Myths' to share with you, about a mystery in Northern Baja from long ago and a

recent search conducted by a Los Angeles policeman named Tad Robinette.

(Bruce Barber's new book, '...of Sea and Sand', has details of Barber's search and possible discovery of the Diaz Grave!)

-------------------------------------------------------------------

THE MYSTERY OF DIAZ' GRAVE

The story of Diaz' grave constitutes a classification all its own -- part history, part mystery, part myth. It will not remain that way forever,

though, if Los Angeles Police Department member Tad Robinette succeeds in his quest.

Upon reading my early Baja book, Robinette got caught up in the challenge of delegating immortality to the neglected hero Melchior Diaz. So in 1994,

putting his military and law enforcement training to test, he set out to settle the Diaz question once and for all.

The explosive history of Diaz' grave first came to my attention through a letter from the late historian Walter Henderson while I was editor of Desert

magazine -- ?explosive? because it refutes several hundred years of fallaciously celebrating Padre Eusebio Kino as the first white man to set foot on

the west shore of the Colorado River. It was that chapter in my book that ignited Robinette's interest.

Baja Califorina's true first European visitor to the northern sector was Melchior Diaz, a beloved Spanish army captain dispatched in 1540 by Coronado

to effect a land rendezvous with Fernando de Alarcon, whose fleet was carrying heavy supplies up the Gulf of California to assist in Coronado's

expedition in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola.

It was during the depression of the early 1930s that Walter Henderson and his southern California companions cranked their Model A Ford roadster

through the rock arroyos of the unpaved road that led toward San Felipe, a Mexican fishing village about 125 miles south of the border at Mexicali. At

a spot a few miles beyond a window-shaped rock formation known as 'La Ventana', they unloaded their camping gear, filled their canteens from a water

tank in the rear of the car, and set out by foot.

On other of their frequent weekend safaris into Baja, if the Ford hadn't drunk too much of their water, they often camped overnight while searching

for old Spanish mines, Indian arrowheads, or whatever else adventure produced. Sometimes they found the powerful horns of a bighorn sheep arched over

its bleached and sand-pitted skull. At other times they heard the screeching wail of a wild cat or caught the fleeting shadow of a mule deer high up

in the Sierras. If a covey of quail flushed from a sparse clump of desert greasewood, they knew that water was nearby. Sometimes they found the

spring; most often they did not. Water is elusive in this rugged, raw land and rarely does it surface in a logical and accessible spot.

But on this cool day in April they were lucky. The Model A had behaved well and used less water than usual and they had managed to drive as far as the

foot of the Sierra Pintos with only three punched tires. Henderson had long fostered a yen to find a way into a canyon oasis he had heard about from

another man named Henderson (Randall, the founder of Desert magazine) who had described an oasis where native blue palms rose above huge granite

basins of water stored from mountain runoffs after storms.

As it turned out, they had hiked too far south. Baja California was only crudely mapped in those days and the Mexican woodcutters who supplied

ironwood for ovens to bake the tortillas of Mexicali and Tijuana had not yet been forced this far below the border, so there was no one to give

Henderson and his party directions.

Throughout the entire Arroyo Grande and Arroyo Tule watershed, they had found no sign of man -- just twisted cacti writhing across the sandy ground,

occasional stubby tarote trees, and lizards basking in the sun. On both sides of the wide arroyo up which they hiked, jumbled boulders stuck like

knobs to the mountainsides. In some areas the mountains were the deep, dark red of an ancient lava flow, in other sectors they were granite, bleached

as white as the sand in the wash.

When night fell, the hikers unrolled their sleeping bags, built an ironwood fire and fell asleep while watching the starry spectacle overhead. In

Baja's clear air, the stars appeared low enough to mingle with their campfire smoke.

At dawn, they brewed a pot of coffee, refried their beans from the night before, and tore hunks of sourdough from a loaf carried by one of the men in

his pack. There was no hurry. They had all day to explore as long as they kept moving back in the general direction of their car.

Late in the afternoon, after hiking across a range of hills, they came upon a curious pile of rocks set back a short distance from the edge of a steep

ravine. For miles around there had been no other signs of human life, neither modern nor ancient. The pile was nearly as tall as a man and twice as

long as it was high. The base was oval and the general shape of the structure resembled a haystack. The stones were rounded rather than sharp-edged,

and although the ground in the vicinity was not littered with them, Henderson and his companions figured that they had been gathered at great labor

from the general area.

They lifted a rock and turned it over. It was dark on the top, light colored underneath. The dark coating acquired by rocks in the desert is called

desert varnish. It is caused by a capillary action of the sun drawing moisture out of the rock. The dark deposit is left from minerals in the water.

In an arid region where rainfall is practically nil, desert varnish takes hundreds of years to form. The fact that these rocks were all coated by

desert varnish on the top indicated that they had remained in their positions for a very, very long time.

The men were tempted to investigate further, but it was the end of April, when the dangerous red rattlers of Baja California come out of hibernation,

so they contented themselves with speculation. The pile of rocks provided an inviting recess for these reptiles and the men were unarmed.

The rock pile stood close to the edge of a narrow ravine that twisted down from the hills over which they had descended. The site was not visible from

the surrounding country so it obviously was not intended as a landmark. That it was a grave, they felt certain, even though it was an unusually

elaborate structure for its isolated situation. Baja California natives have always conscientiously buried corpses found in remote countryside, but

usually the grave is simply outlined with a series of rocks rather than built up man-high like a monument. Whoever lay beneath this rock pile was

obviously revered by his companions who must have numbered more than a few in order to erect it.

Tilted against one end of the rock pile was an ancient piece of weathered ironwood nearly a yard long and as thick as a man's thigh. If a smaller

crosspiece had been lashed to it to form a cross, the addition had long ago eroded away. Ironwood, Olneya tesota, is a tall spreading tree found only

in washes of hot desert areas in the Southwest. Its wood is brittle, very hard and heavy, and it burns with a slow, hot flame. Mexican woodcutters

have all but depleted the desert of it in recent years, but during the 1930s when Henderson discovered the mysterious grave, it still was conceivable

that the heavy log could have been found close enough to drag to the graveside.

By this time the sun was falling low in the mountains behind them, so the men left the pile of stones and hurried on across the desert to reach their

car before nightfall. They never had occasion to return.

Two years later, however, the memory of the mysterious pile of rocks rose to taunt Henderson and continued to do so for the rest of his life.

The Narratives of Castaneda had been translated into English and a copy had fallen into his hands. When he came upon a passage that read " on a height

of land overlooking a narrow valley, under a pile of rocks, Melchior Diaz lies buried," he would have known immediately that he had found the lost

grave of this Spanish hero except for the fact that Pedro de Castaneda, who traveled as a scribe for Coronado, believed that Diaz was buried on the

opposite side of the Colorado River. However, Castaneda wrote his manuscript twenty years after it had happened and, since he was with Coronado rather

than with Diaz, his only authority was hearsay.

Melchior Diaz would have been completely ignored by history had it not been for the exploits of Fernando de Alarcon, who had been fitted out with two

vessels and sent up the Gulf of California by Viceroy Mendoza to support Coronado?s land expedition. A rendezvous had been arranged at which time the

land forces were to pick up supplies that Alarcon would bring by sea. As Coronado and his forces moved north, however, their guides led them further

and further toward what is now New Mexico, and away from the Gulf where they were to meet Alarcon. When Alarcon arrived at a lush valley near an

Indian village far east of the Gulf, he established a camp and dispatched Melchoir Diaz westward with a forty-man patrol mounted on his best horses to

search for Alarcon?s ships and make a rendezvous on the Gulf.

Diaz, traveling west, arrived about 100 miles above the Gulf on the bank of the Colorado River. There he learned from an Indian who had helped drag

Alarcon's boats through the tidal bore that Alarcon had been there, but was now down river and had left a note on a marked tree near where the river

emptied into the Gulf.

Diaz then marched south for three days until he came to the marked tree. At the foot of it he dug up an earthenware jug with contained letters, a copy

of Alarcon's instructions, and a record of the nautical expedition's discoveries up to that point.

Knowing now that Alarcon was returning to Mexico, Diaz retraced his steps up the river to what is now Yuma, Arizona, where he forded the river. The

trail through Sonora by which he had come north took his army far inland from the sea. In the event that Alarcon still lingered in the area, Diaz

hoped that by following down the West Coast of the Gulf his men might be able to stay closer to the shore and thus sight the ships.

Marching southward from the present Yuma where they had crossed the Colorado, Diaz and his men came upon Laguna de los Volcanoes, about thirty miles

south of Mexicali. It is from this point that the narrative grows vague, except for the historical account of Diaz' fatal injury and subsequent

burial.

The injury occurred one day when a dog from an Indian camp chased the sheep that accompanied his troops. Angered Diaz threw his lance at the dog from

his running horse. Unable to halt the horse, he ran upon the lance that had upended in the sand in such a fashion that it shafted him through the

thigh, rupturing his bladder.

References vary as to how long he lived following the accident. Castenada reported that Diaz lived for several days only, carried on a litter by his

men under difficult conditions over rough terrain.

Castaneda's report may be flawed. Not only did he write it twenty years after the fact, but his report was based on hearsay evidence since he was with

Coronado in what is now New Mexico and not along the Colorado with Diaz. A more modern historian, Baltasar de Obregon, wrote that Diaz lived for a

month following the accident. Herbert Bolton, the distinguished California historian, wrote that after crossing the Colorado River on rafts, Diaz and

his troops made five or six day-long marches westward before turning back after Diaz' injury.

If Bolton's information relative to the days that they marched is correct, and if Castaneda is accurate relative to the number of days Diaz lived

after the accident, Diaz is buried on the West Coast of the Gulf. If he lived for a month, however, his grave very likely lies on the Sonora coast.

This has never been established, although historians have searched fruitlessly for the grave on the East Coast of the Gulf for several centuries.

So convinced was Henderson that he had found Diaz' grave that he proposed an investigation to the Mexican consul in Los Angeles. He was received

politely enough, but turned away with the deluge of problems his suggestion encountered. He was told that to conform to Mexican law of that time his

search party must consist of from two to four soldiers, an historian with official status, a guide to show them where they wanted to go, a cook to

feed them, and mules and saddles so the Mexican officials 'would not have to walk or carry packs on their backs like common peons.'

In addition, the party would have to include someone to put the mules to bed and saddle them, a muleteer, and a security guard to protect Diaz'

helmet, leather armor, blunderbuss, broadsword, coins, jewelry and whatever else of value accompanied the skeleton in the grave. All this was to be

paid for by Henderson. A further stipulation stated that if the area turned out to be too dangerous or rough for the retinue involved, regardless of

expense incurred, Henderson would be obliged to call off the whole thing and turn back.

This, during those years of the depression, was out of the question for Henderson, or just about anyone else. In later years the rigors of such a trip

for Henderson were too great. Faced with those complications, he ultimately went to his own grave never having solved the mystery of Diaz, but haunted

throughout life by the memory of that mysterious pile of rocks. So Diaz sleeps, a neglected hero while Mexicans and Americans alike pay homage to the

prevalent belief that Padre Eusebio Kino was the first white man to come ashore on the west side of the Colorado River.

Now that Baja has come into its own as a popular destination, the present government might be more amenable to investigating the gravesite if it can

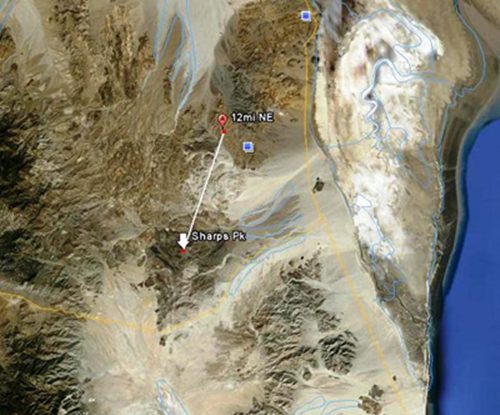

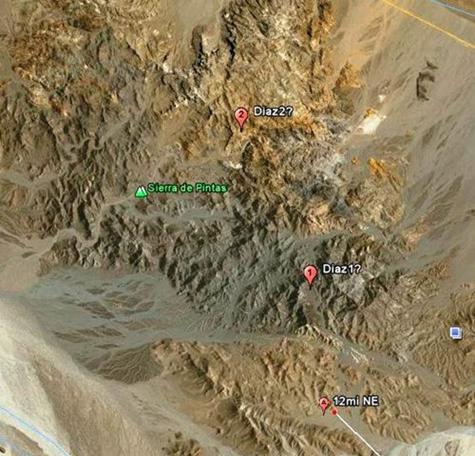

be found. According to Henderson's directions, a line drawn on the hydrographic chart of the Gulf of California from Sharp Peak (31 degrees 22 minutes

N. Lat., elevation 4,690, 115 degrees 10 minutes W. Long.) to an unnamed peak of 2,948 feet, NE from Sharp peak (about twelve miles away) will roughly

follow the divide of a range separating the watershed that flows to the sea. Somewhere near the center of that line, plunging down the westerly slope,

is a rather deep rock-strewn arroyo. On the north rim of this arroyo, and set back a short distance, is a small mesa-like protrudence, or knob of

land. There may be a number of arroyos running parallel. It is on one of these where the land falls away to the west that the rock pile overlooks the

arroyo. That was as close as Henderson was able to identify it on a map.

On one of my flights with Gardner in the 1960s, as we flew over land and water to Sierra Pinto, some thirty-two land-miles north of San Felipe, I

looked for a rugged ravine plunging down from the east side of Cerro del Borrego, a peak north of the present intersections of Highways 5 and 3, but

even the practiced eyes of pilot Francisco Munoz, who circled the area several times, were not sharp enough to etch a rock-covered grave out of the

colorless land. We did detect a dirt road about ten miles south of the La Ventana marker on modern maps that led into ruins of an old mine called La

Fortuna. That may have been where Henderson and his friends left their Model A Ford and initiated their hike.

So much for my treasure hunting competence!

But if any reader has ever doubted the efficiency of an L.A.P.D. cop, put your mind at rest. I have dealt with many treasure hunters, professional and

otherwise, but never have I encountered an equal in systematic persistence to Tad Robinette. Because of his intensive approach toward solving this

mystery, I shall recount it in detail as he reported to me.

Consistent with law enforcement training, Robinette?s modus operandi depended upon finding a good topographical map of an area relatively unmapped in

Henderson's day. After a series of long-distance calls around the United States, he finally located a store in North Carolina that stocked Mexican

topo maps. Within weeks, he had a collection of the best on the market. They were helpful, but obviously not the map that Henderson had consulted.

That one, Robinette determined, was probably a hydrographic map detailing the Gulf of California area north of San Felipe, since no detailed land maps

had been made at that time. The hunt then began for a hydrographic chart dated prior to 1950.

At about this time Robinette learned of a library in the basement of the Los Angeles Natural History Museum that contained old maps, including

hydrographic charts. Access, by appointment only, was arranged through the curator. Robinette arrived at his appointed time, was escorted through two

sets of double doors, and then turned loose in a basement room lined with volume upon volume of obscure books, old magazines, and stacked layers of

professional papers. He came upon a map section. No numbering system was used. The maps were haphazardly placed in drawers. By chance he found a small

collection of hydro maps dated between 1880 and1930. Among them was a copy of the very map used by Henderson denoting the same peaks and elevations.

Because nothing could be removed from that library, Robinette made notes to facilitate ordering a copy directly from the archives in Washington, D.C.

Three months later he possessed it.

He then painstakingly coordinated grids provided by Henderson's recollections superimposed upon modern detailed topo maps, geological surveys,

historical records of the Coronado expedition, and the projected distance for a day's march. This way he identified the most likely areas for

exploration.

It wasn't until 1998, however, that Robinette had accumulated enough information and time off work to convince him that a personal expedition was

worthwhile. Then, limited to two days that included the drives back and forth to Los Angeles, he got a good look at the 'lay of the land' south of the

border, but not much else.

His second trek, a year later, lasted for three days. This time he was rewarded by a fine rosy quartz vein, some spectacular sunrises, and a lot of

mountain climbing experience, but he did not find the grave.

Trek Number Three had to be postponed until the year 2000. Then, accompanied by his partner on the beat, Jamie Cortes, they attacked the landslides,

the defiles, and the cactus-covered lava mountains with vigor. During this trip they scoured the mid-section of the area Robinette had designated on

his map. On the last day they had an encouraging break. They had come upon a low range of rolling hills after descending from Arroyo Grande that

matched Henderson's recollection. But their time was up. The Los Angeles Police Department call to duty waits for no man.

So now we come to Trek Number Four. This time a third partner, Paul Dean, joined the hunt. Unfortunately, the promising 'low range of rolling hills'

failed to keep its promise.

After exceeding the limits of exploration, Robinette had initially projected on his maps, time ran out again. Tired and discouraged, the party was

straggling along a rough route in the direction of the car they had left behind when they came upon an unexpected pass that would have provided

Henderson's party, as well as their own, a lower and easier route back to the La Ventana area where their car was parked. This appeared at the end of

their allotted time, of course -- the destined fate of most treasure hunts! So they made a haphazard survey and left, promising themselves a return

next year.

As I have written before, I'll write again, "Adventuring in Baja is like a Navajo rug with the traditional loose thread left dangling. To finish the

rug would be to kill it. As long as it is unfinished, its spirit is still alive." Now who wants to kill adventure? Certainly not Tad Robinette. Nor do

I.

So, as Robinette ended his report to me, I'll end this book, "To be continued"

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

Baja is filled with these wonderful stories that inspires exploration and discovery. Thanks to Choral for giving me the ability to share this with

fellow Baja enthusiasts! See http://ChoralPepper.com

Footnote: Bruce and Tad have been given the original letter and directions that Henderson mailed to Choral, which I now have.

[Edited on 7-15-2011 by David K]

|

|

|

Baja Bernie

`Normal` Nomad Correspondent

Posts: 2962

Registered: 8-31-2003

Location: Sunset Beach

Member Is Offline

Mood: Just dancing through life

|

|

David

Happy that you are now posting Choral's stuff here.

Thanks

My smidgen of a claim to fame is that I have had so many really good friends. By Bernie Swaim December 2007

|

|

|

Mexitron

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3397

Registered: 9-21-2003

Location: Fort Worth, Texas

Member Is Offline

Mood: Happy!

|

|

Wow...interesting mystery! Sounds like a great exploration to try...

|

|

|

Von

Senior Nomad

Posts: 961

Registered: 10-1-2006

Location: Poway-Rosarito

Member Is Offline

Mood: getting ready!

|

|

pretty cool stuff David Im glad theres people who love baja as much as I feel for it. Thanks man.

READY SET.....................

|

|

|

Barry A.

Select Nomad

Posts: 10007

Registered: 11-30-2003

Location: Redding, Northern CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: optimistic

|

|

David-------

As always, great stuff!!!!! the grave is like looking for a needle in a haystack, but what an adventure trying to find it. Someday, somebody

(you??) will find that pile of rocks, the grave site, I am betting. but, that Arroyo Grande area is so huge, and non-descript that it will be a real

challenge.

Thanks so much for posting this.

|

|

|

Mango

Senior Nomad

Posts: 685

Registered: 4-11-2006

Location: Alta California &/or Mexicali

Member Is Offline

Mood: Bajatastic

|

|

Great post David.

I have my Baja Almanac out right now. The area is not far from here and I have been meaning to poke around the La Fortuna mine for a while now.

This gives me a great excuse to head down there as soon as it cools off a bit.

|

|

|

TacoFeliz

Nomad

Posts: 268

Registered: 7-22-2005

Location: Here

Member Is Offline

Mood: Exploratory

|

|

Very cool, David! Keep 'em coming. I'm guessing Google Earth usage spiked a bit when you posted Choral's story... I got out my topos.

|

|

|

Gnome-ad

Nomad

Posts: 156

Registered: 6-4-2007

Location: Todos Santos, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: Okey-Dokey

|

|

Thanks. Very interesting from both the modern and historical perspectives.

The only normal people are the ones you don't know very well. - Ancis

|

|

|

Neal Johns

Super Nomad

Posts: 1687

Registered: 10-31-2002

Location: Lytle Creek, CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: In love!

|

|

David K,

Sorry, but you are wrong about his location - I know because I was there when we buried him.

My motto:

Never let a Dragon pass by without pulling its tail!

|

|

|

Gadget

Senior Nomad

Posts: 851

Registered: 9-10-2006

Location: Point Loma CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: Blessed with another day

|

|

VERY COOL! I have a new Baja jones.

"Mankind will not be judged by their faults, but by the direction of their lives." Leo Giovinetti

See you in Baja

http://www.LocosMocos.com

Gadget |

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

2009

Any new interest to solve this Baja Mystery?

I have shared this chapter of Choral Pepper's book on Nomad a couple times since 2004... and hope to inspire some exploration of the desert. This

year's Baja 1000 is going very near the area in question (Cerro Borrego/ Sierra Pintas) so I thought about exploring the information again... This is

also near the Pole Line Road built in World War II by the U.S. for a telephone line to San Felipe where we had a radar station/ observation outpost.

In addition to the chapter in Choral Pepper's old and newer (unpublished) book copied above, I also have the original letter and directions from

Walter Henderson mailed to Choral in 1967 about his 1930's discovery... A serious expedition is in order, if only to find the same pile of rocks.

Should there be a Spanish officer's helmet, sword, or other items that prove it was the 1540 grave from the first land expedition to California, then

that needs to be in a museum (wise words from Dr. Indiana Jones).

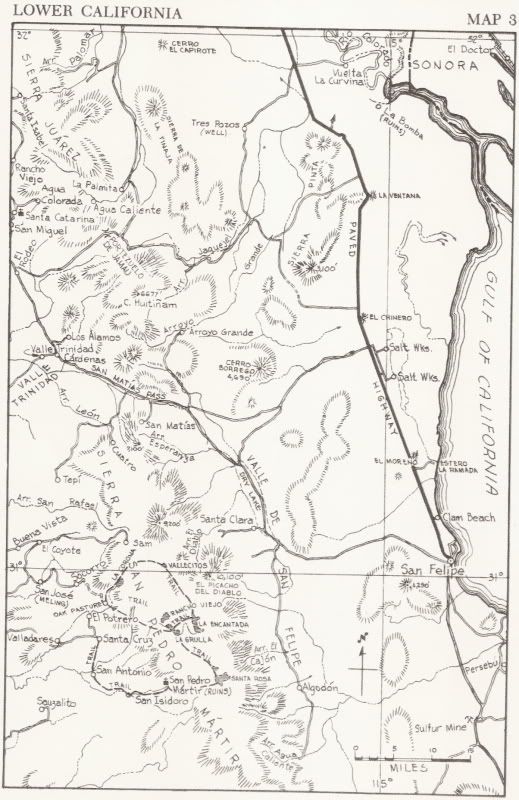

Here is the region as drawn in 1962...

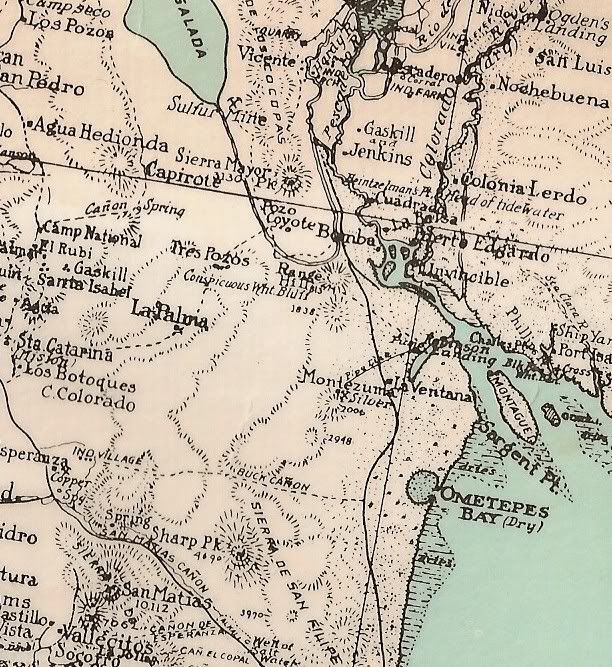

In 1930...

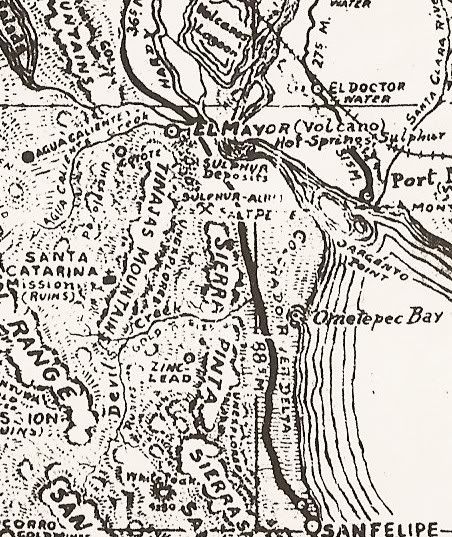

In 1941...

The desert is a wonderful place, but ignored because of its harshness unless people are motivated to discover and appreciate it. Choral always wanted

her books and articles to encourage people to know the desert she loved.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

This point:

"It was during the depression of the early 1930s that Walter Henderson and his southern California companions cranked their Model A Ford roadster

through the rock arroyos of the unpaved road that led toward San Felipe, a Mexican fishing village about 125 miles south of the border at Mexicali. At

a spot a few miles beyond a window-shaped rock formation known as 'La Ventana', they unloaded their camping gear, filled their canteens from a water

tank in the rear of the car, and set out by foot."

In Choral's previous versions of this story, she said they parked at La Ventana (the window in the rock, perhaps near today's La Ventana on Hwy. 5).

It was this starting point error that threw off early searchers.

The original letter from Henderson gives good details as to where they drove the Model A and began their hike.

More details yet to come!

[Edited on 10-28-2009 by David K]

|

|

|

dezertmag

Newbie

Posts: 6

Registered: 10-25-2009

Location: california

Member Is Offline

|

|

Hey David,

This has the makings of a GREAT story !!!! I wonder if there is anyone near this place that could take a look, or get some pixs ???

DezMag

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

I hope to go this winter! Nomad 'bajalou' and his followers from El Dorado Ranch are the closest... and Nomad 'MICK', at Rio Hardy.

Tad Robinette has made like 4 trips into the area... and if he was given the same details from Choral that I now have, I think he would have found it?

It is just a large pile of rock, not natural, and in an area that people were not yet traveling in the 1930's.

It was AFTER their hike that Walter Henderson read the story about Melchior Diaz and believed his rock pile was the 1541 gravesite.

I only ask anyone who finds it first, to please take several photos from various angles... I can cantact INAH and an archeologist who has permission

to work in Baja, if the site looks promissing... Just as I did when (with help from Sharksbaja) we re-found the ruins of a possible proposed mission

site 'Santa Maria Magdalena' that Choral Pepper and others on the 1967 Erle Stanley Gardner expedition saw... http://vivabaja.com/109

|

|

|

dezertmag

Newbie

Posts: 6

Registered: 10-25-2009

Location: california

Member Is Offline

|

|

Hi Gang,

I was trying to see if I can come " close " to where this might be, and I found some very small formations that I placed a tag at. Take a look and

see what you think. I used the instructions as follows " According to Henderson's directions, a line drawn on the hydrographic chart of the Gulf of

California from Sharp Peak (31 degrees 22 minutes N. Lat., elevation 4,690, 115 degrees 10 minutes W. Long.) to an unnamed peak of 2,948 feet, NE from

Sharp Peak (which I think is Cerro del Borrego -about twelve miles away) will roughly follow the divide of a range separating the

watershed that flows to the sea. Somewhere near the center of that line, plunging down the westerly slope, is a rather deep rock-strewn arroyo. On the

north rim of this arroyo, and set back a short distance, is a small mesa-like protrudence, or knob of land.

Ok... I can't seem to post the pixs... Can anyone help with this??? I don't have them on a site they are on my computer...

John

DezMag

[Edited on 11-1-2009 by dezertmag]

[Edited on 11-1-2009 by dezertmag]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by dezertmag

Hi Gang,

I was trying to see if I can come " close " to where this might be, and I found some very small formations that I placed a tag at. Take a look and

see what you think. I used the instructions as follows " According to Henderson's directions, a line drawn on the hydrographic chart of the Gulf of

California from Sharp Peak (31 degrees 22 minutes N. Lat., elevation 4,690, 115 degrees 10 minutes W. Long.) to an unnamed peak of 2,948 feet, NE from

Sharp Peak (which I think is Cerro del Borrego -about twelve miles away) will roughly follow the divide of a range separating the

watershed that flows to the sea. Somewhere near the center of that line, plunging down the westerly slope, is a rather deep rock-strewn arroyo. On the

north rim of this arroyo, and set back a short distance, is a small mesa-like protrudence, or knob of land.

Ok... I can't seem to post the pixs... Can anyone help with this??? I don't have them on a site they are on my computer...

John

DezMag |

John, send it to me... if you can't get it to post. What I do is use Photobucket.com which has several auto resize choices (use 15" monitor size or

smaller)... Any other web site also could host the photo and then just hotlink the photo URL here. For Nomad to host the photo off your PC, it needs

to be sized below 50 KB... then use the Browse button to find that file and post it on Nomad.

|

|

|

dezertmag

Newbie

Posts: 6

Registered: 10-25-2009

Location: california

Member Is Offline

|

|

Hey Gang,

Ok here is the 2nd pix..... Thx david

|

|

|

bajalou

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4459

Registered: 3-11-2004

Location: South of the broder

Member Is Offline

|

|

It sounds like a great hunt for me. As you know, I'm friends with Bruce Barber, who spent several years researching and searching, without the help

of Pepper's papers. Be great to give him a picture of the elusive spot.

No Bad Days

\"Never argue with an idiot. People watching may not be able to tell the difference\"

\"The trouble with doing nothing is - how do I know when I\'m done?\"

Nomad Baja Interactive map

And in the San Felipe area - check out Valle Chico area |

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by bajalou

It sounds like a great hunt for me. As you know, I'm friends with Bruce Barber, who spent several years researching and searching, without the help

of Pepper's papers. Be great to give him a picture of the elusive spot. |

Yes, I have had long conversations with Bruce about Choral and the Diaz grave... which to be accurate was only called "a rock pile" by Walter

Henderson. But, what else does one do in the desert but look for a 'pile of rocks'?

I did share the Henderson letter with Bruce and Tad... they both did a lot of investigative research and deserved to have the prime clue, which was

given to me after Choral passed on, in a cardboard box full of letters and photos from her Baja trips and Desert Magazine publishing days.

Baja Off Road and Historic fun with an Indiana Jones twist!

|

|

|

mtgoat666

Platinum Nomad

Posts: 20647

Registered: 9-16-2006

Location: San Diego

Member Is Offline

Mood: Hot n spicy

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by David K

But, what else does one do in the desert but look for a 'pile of rocks'?

|

based on this forum, it appears that most frequent thing done in desert is drugs (alcohol)

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3

..

6 |

|