| Pages:

1

2

3

4 |

güéribo

Nomad

Posts: 239

Registered: 10-17-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

Hello, Sargento. The books you mentioned are quite detailed. The only difficulty is that the authors are both priests. So used alone, those texts

don't provide a complete picture. For myself, I think it's important to hear the voices of the less powerful in addition to the conquerors.

Sometimes that is difficult. I know that many do disregard the native oral tradition passed down through the generations, but I consider oral

tradition a valid source of history.

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

Good morning. . The views and interpretations I published 20 years ago have not changed. In recent years I have written about 16th century missions in

central Mexico, and my next book to be released next month deals with Jesuit missions in Paraguay and the CHiquitos region of eastern Bolivia. THe

frontier mission was first and foremost a colonial institution, and the missionaries came with intellectual baggage and were steeped in a eurocentric

belief in cultural superiority. Mistreatment of natives who did not tow the line was part and parcel of tof mission program, and was authorized by

Spanish law. In my recently published book VIsualizing the Miraculous, VIsualizing the Sacred, I reproduced an illustration from the Lienzo de

Tlaxcala (c. 1580) showing the execution of a group of indigenous leaders in Tlaxcala accused of practiocing their traditional religious beliefs.

Martin de Valencia, O.F.M., one of the first group of Franciscan missionaries in Mexico, orchestrated the executions, done by hanging or being burned

at the stake. One of those executed was an indigenous noble woman. In 1539, Juan de Zumarraga, O.F.M., culminated his inquisition campaign with the

execution of Don Carlos, an indigenous leader from Texcoco, who was burned at the stake in Tlatelolco. After the execution of Don Carlos, the Crown

stripped Zumarraga of his authority, and prohibited the execution of natives, and particularly native leaders. The Crown realized that the tactics

the Franciscans employed would cause more damage than good. However, despite backtracking on the issue of the execution of natives, the same

eurocentric view undeerlay all mission on all frontiers.

Engelhardt and Guest are useful sources of information, and I have used data from Engelhardt. I met Guest years ago. Engelhardt and Guest were

extremeely biased, and in particular Engelhardt was a racist and Guest was not too far from that. Many did not like my views on the missions, but one

Franciscan who wrote a review of Indian Population Decline said that the numbers speak for themselves, and people had to deal with that reality. Not

all Franciscans were or are biased. I had a very good personal relationship with the late Kiernan McCarty, who was very supportive of my research

despite being a Franciscan. Antonine Tibesar, O.F.M. was alsso more open minded, and invited this heretical historian to participate in a conference

in 1984 dedicated to Serra-the papers from the conference were later published in The Americas, the journal of the Academy of American Franciscan

History.

In my personal view, Serra was not a saint. The facts speak for themselves. The whole issue needs to be placed within the context of the larger

colonial agenda. Serra and his group of Franciscans from the Apostolic College of San Fernando were particularly harsh towards natives, and there is

evidence of this from the Sierra Gorda missions as well as from the Baja California missions. Natives congregated on the five Sierra GOrda missions

Serra administered fled because of conditions on the missions. Franciscans from the Apostolic College of Pachuca administered missions in the same

area, and used a different approach that was not as disruptive of native life ways. Natives who fled from the Fernandino missions chose to go to the

missions administered by the Franciscans from Pachuca.

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

In 1748, a group of Jonaces living on San Joose de Viarron mission )Queretaro= fled because of the way the Franciscans adminiistered the mission. This

was before Serra arrived in the Sierra Gorda. Soldiers recaptured the fugitive Jonaces, and placed them in forced labor in textile mills in Queretaro

City, which is a short distance away. Some Jonaces went to Pacula mission in what today is Hidalgo state. The Franciscans from Pachuca administered

thiis mission, and did things differently. Serra pioneered the methods later employed in Baja California and California during his period in the

Sierra Gorda. Two key eleemnts were to convert the natives into a disciplined labor force to support the colonial economic system, and to enhance

econoomic depeendeence on the missions as sources of food. The episode with the Guaycuros in southern Baja Californiia exemplified the approach Serra

and his colleagues took in the administration of the missions.

|

|

|

güéribo

Nomad

Posts: 239

Registered: 10-17-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

Hello, academicanarchist. I'm glad you weighed in. I was hoping you would. Always appreciate your scholarship.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65398

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Thank you Robert!

|

|

|

sargentodiaz

Nomad

Posts: 259

Registered: 2-20-2013

Location: Las Vegas, NV

Member Is Offline

|

|

And the controversy continues. I was very impressed with the detailed posts on the Sierra Gorda missions and was most surprised to read that the

Apostolic College of San Fernando had such a policy.

That leads to one question - if Father Serra and his fellow friars were so harsh, why did hundreds, even thousands flock to the missions - and

willingly stay there?

I am no fan of Bancroft but he, even as anti-Papist as he was, had nothing but glowing things to say about the friars and their efforts with the

Indians he claimed to be little more than animals.

I simply cannot image that 2 friars and no more than 5 soldiers could cow and maltreat all the Indians at each mission.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65398

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Good questions indeed... they were attracted to the missions for the food (at least in Baja, where the ones inland ate most anything, so the mush

"pozole" the Spanish made had to be much better). Curiosity was the other... horses, mules, farm animals, cattle... obviously the Spanish were advance

beings.

As I reported before, the missionaries also stopped the tribal killings, abortions, cruelty to elders, etc. all performed by the 'peaceful' natives...

so perhaps that was attractive to some. Women joined the mission often without the men, who naturally followed them later. Perhaps they felt safe from

rape, starvation, or hostility in the mission?

The bad thing that came and was not desired or intentional, was the sickness and disease introduced to the natives. If not from the missionaries or

soldiers, then it would come from sailors and pirates. There was no escape from that, rather it came during the mission period or at another time.

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

A very complex question that I have discussed in my publications, as have others including Randy Milliken in his study "A Time of Little Choice,"

which sums up the problem in the California missions. One factor was the rapid proliferation of mission livestock (talking about the California

missions) that consumed food sources previously exploited by the indigenous populations. The Franciscans consciously had livestock placed to native

communities, in part, to have a food source. Thousands of cattle and sheep destroyed seed producing grasses, and ate acorns. By the first years of the

19th century the environment in California had changed, especially in the coastal areas, and it independent native communities could no longer survive

outside of the missions.

|

|

|

güéribo

Nomad

Posts: 239

Registered: 10-17-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

It is indeed a complex question.

In the book, "Kiliwa Texts: When I Have Donned My Crest of Stars," Rufino Ochurte, a Kiliwa, shares oral tradition that presents the mixed reactions

of the tribe to the priests. I sense in his narrative how some were curious and drawn, and others fearful and repulsed. He tells the story in a

manner common in some indigenous cultures--rather than a linear order of events, it progresses in a more circular way, with repetition of ideas.

Ochurte relates (in his native language, translated in the text):

There were people-not-washed (ie. unbaptized) in this land. In the mountains, there were the Kiliwa people. A friar came. No one drew near.

Because of that, he'd just lash out and grab them. He did that once or twice. He'd do it to all the people that way. He'd catch them; when they'd

get used to him, they wouldn't flee. 'Well, the way I am, it's really fine' they say. That was the way that, one or two at a time, they would

arrive. Until there were many people at the mission. They made people work, whipping them when they were uncooperative. They gave them gruel to

drink so that they'd work. They constructed houses as best they could. Although they didn't earn anything, they did eat. To those with a family,

they gave a sackful of corn. They'd eat at the mission. If someone was disobedient, they'd grab him and whip him. They would dunk people to baptize

them: 'This is a good thing I'm doing!' he (the priest) declared when he was finished. 'You might tell the others,' he would say. They'd come and

tell about it: 'This man is going to do that to us!' 'No indeed! One never knows what might happen,' they'd answer. No one at all would come near.

And so it continued for some time. Slowly they took hold of the people. In the end, the people came to the friar. They all became docile. There

was no one who would decide for himself where to go anymore. There weren't many who went to the mission. They'd come around very little. While the

friar was about his things, they'd watch and comment. They slowly began to draw closer. Yet, though they approached, they really didn't hang around

very much. They'd say, 'It's alien! It's evil!' 'You never know,' they'd say. They'd remain yonder (at a distance). By proselytizing he kept the

people away. Eventually however the friar lulled the people completely . . . they would be sponsored (as godchildren). And so they gathered the

people up . . .

----

In the next account, Ochurte describes how the tribes attacked and burned the mission (Santa Catarina, 1840).

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

Manuel Rojo also recorded accounts by indigenous people from northern Baja California, including one named Jatinil who described being brought to the

mission by force and later being whipped for breaking a hoe.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65398

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Jatiñil vs. Janitín ?? Same or different persons??

Quote: Originally posted by academicanarchist  | | Manuel Rojo also recorded accounts by indigenous people from northern Baja California, including one named Jatinil who described being brought to the

mission by force and later being whipped for breaking a hoe. |

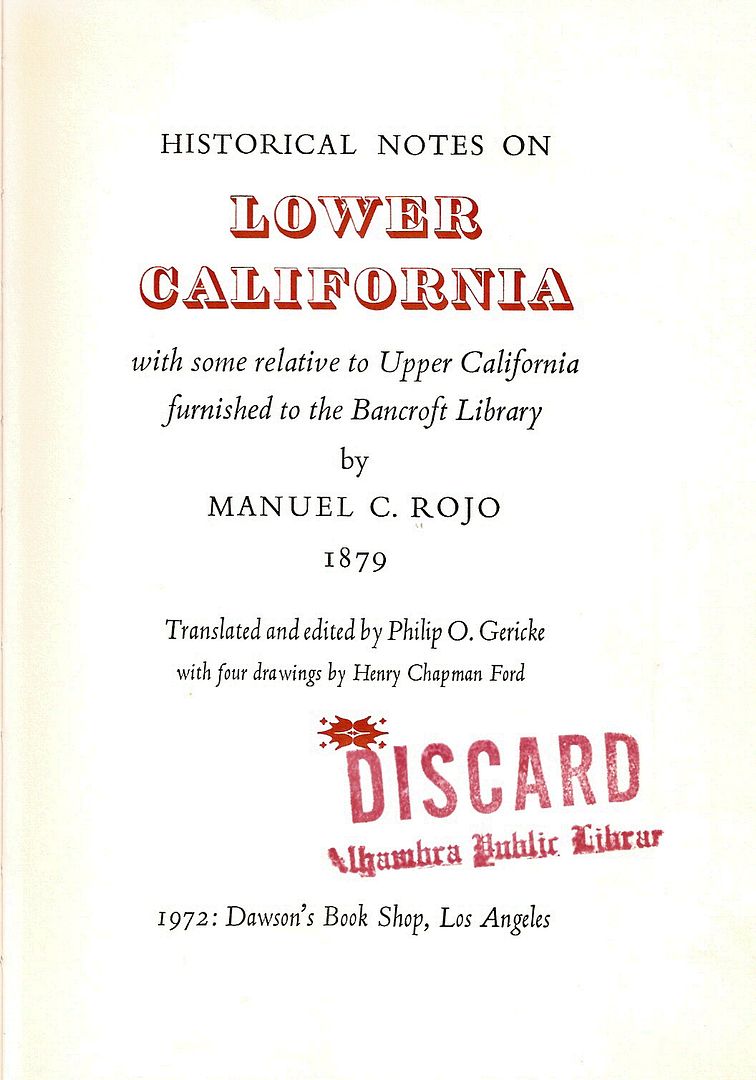

This is #26 of the Dawson Baja California Traveler's Series..

Jatiñil (Jatñil) was the chief (1822-1870+) of a band of Indians from Nejí who originally helped the missionary Felix Caballero build El Descanso

(1830) and Guadalupe (1834). Jatiñil also sided with the Mexican soldiers against the Indians who attacked Mission Santa Catalina in 1834. In 1840*,

Jatñil turned against Padre Caballero at Guadalupe in anger for forcing baptism on his tribe's females. Caballero hid in the mission choir loft under

the skirt of an Indian woman (María Garcia) after he begged her to not turn him in. Caballero fled to San Ignacio where he died mysteriously a few

months later, after drinking his morning cup of chocolate.

(*some accounts say 1839)

Janitín was interviewed as an old man and related a story of being captured on the beach of Rosarito while digging clams with two relatives. Janitín

was captured, tied and dragged while his relatives escaped and hid. They forced him to keep up with them on horseback all the way back to Mission San

Miguel (today's La Misión), whipping him when he didn't keep up. At the mission, the priest forced conversion upon him and gave him the name 'Jesús'.

Later, while forced to work the fields with a hoe, he cut his foot and couldn't stand, so he used his hands instead to pull weeds. That afternoon he

was whipped for not finishing his job, and this repeated daily until he was able to escape. He was caught at La Zorra and when returned to San Miguel

was whipped and those scars remained with him to old age. Janitín escaped again and remained in the mountains for many years and didn't return to the

coast until after the missions were finished.

Notes in the translated edition of Rojo's papers indicate that Janitín is a misspelled version of Jatiñil. However, the story does not match the

events:

The northern missions of San Miguel, Descanso, Santa Catalina, and Guadalupe were all closed between 1834 and 1840 and their priest (Caballero) was

run off by Jatiñil, who had helped Caballero build Descanso and Guadalupe (1830 & 1834).

Janitín escaped from San Miguel and hid in the mountains until after the missions were closed. Clearly not what Chief Jatiñil did.

|

|

|

grizzlyfsh95

Nomad

Posts: 226

Registered: 1-8-2010

Location: East Cape

Member Is Offline

|

|

The great thing about writing history, is that you can make it anything you want it to be. Just take the perceived end result (your own bias) and

create a story that explains it. Folks have been doing it for years. Emphasize this, de- emphasize that, put whatever spin you want on it.

The harder I work, the luckier I get

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65398

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

It is just great fun to read the letters from people who were there back then and gain insight at least on their feelings if not the actual unbiased

facts.

|

|

|

DianaT

Select Nomad

Posts: 10020

Registered: 12-17-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by grizzlyfsh95  | | The great thing about writing history, is that you can make it anything you want it to be. Just take the perceived end result (your own bias) and

create a story that explains it. Folks have been doing it for years. Emphasize this, de- emphasize that, put whatever spin you want on it.

|

Yes, there has NEVER been a history book written that is not biased in one way or another. And one really needs to be careful when they read original

letters and accounts of events, especially when the writers are talking about people to whom they feel far superior.

The oral history tradition is such an important part of history that is often ignored. It is as factual as is the written history---

[Edited on 3-30-2015 by DianaT]

|

|

|

güéribo

Nomad

Posts: 239

Registered: 10-17-2014

Member Is Offline

|

|

Well said, DianaT.

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

Janitin.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65398

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Do you think they are different people as I do?

Rojo's book translator thinks they are the same, and he can't figure out why only in that paper is Jatiñil spelled Janitín!

Because they are different people!!

|

|

|

sargentodiaz

Nomad

Posts: 259

Registered: 2-20-2013

Location: Las Vegas, NV

Member Is Offline

|

|

Professor Mendoza is a fallen-away Catholic who has revisited Father Serra's story. This is a well-written article that I think clearly states a case

for the reverend father

In Support of Father Serra

With the pope's announcement that he is going to make the founder of the California missions a state, isolated small groups and intellectuals are

attacking this decision.

As someone who has studied Father Serra's life, this article is quite heartwarming and it corroborates what I've come to feel about this devout and

caring man. Here is a quote from the article that says what needs to be said:

| Quote: |

“I began to realize: especially the most malicious comments about Fr. Serra were usually by people who knew nothing about him, who had picked it up

secondhand on the internet or on a blog, or who simply just didn’t care for the Catholic Church and its doctrine.” |

The full article can be read @ http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/news/history-truth-and-pol...

|

|

|

academicanarchist

Senior Nomad

Posts: 978

Registered: 9-7-2003

Member Is Offline

|

|

David. It has been years sincee I looked at Rojo, but as I recall I believed they were tw different people.

|

|

|

sargentodiaz

Nomad

Posts: 259

Registered: 2-20-2013

Location: Las Vegas, NV

Member Is Offline

|

|

I see no response to my last post.

Wonder why.

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3

4 |