| Pages:

1

2 |

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Consag interrupts a Cochimi image burning ceremony.

"On the 14th we reached the place inspected before and we stopped on a slope in front of the settlement. There are on its declivities some small dug

wells of brackish water and at the foot the large ravine.

On the other side there are some other small wells in which there is more and better water. To this the mounts were taken and the majority of our men

too, provided themselves with this water.

The natives had aban- doned their settlement and scattering over places that were rough and broken, they very timely carried away or concealed their

household utensils together with the idols that they are wont to keep in a house or bower apart from the town, so that the settlement looked as if

deserted.

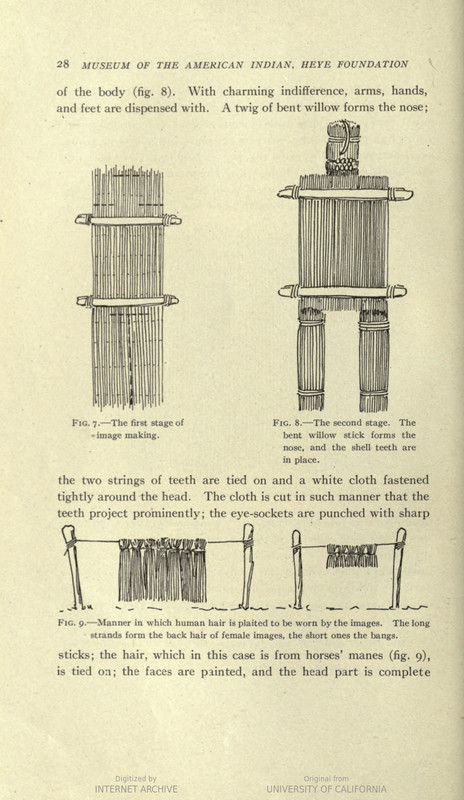

These miserable and unfortu- nate barbarians make their idols out of any kind of grass reinforced with sticks. In their faces (I had better say) in

the place of the one they ought to have, you see a kind of a cap that they make of black feath- ers woven into the knots of a hair net in the manner

of a wig and it is among their most ingenious pieces of work.

The ears of some of them are of wood; for shoulders they put a little board on each side, about six inches long, thin and painted. Moreover, we mar-

veled at seeing the Holy Cross there. A plumage made of various feathers serves them as a crown.

From the neck over the chest there hang many strings of small shells, of snails, little nuts and various colored feathers, that the greater part of

the adornment con- sists of, and that in their blind and barbarous opinion constitutes all the wealth.

Some of them have a piece almost a half yard long and about a quarter or one- third wide of a course texture of Agave and crudely variegated with

earthen paints. Some skeins of hair knotted and braided above, hang like a cloak or mantle of state from the madly false divinity.

All this finery they are wont to keep in little baskets of rushes not woven but tied at certain distances in such a way that when they open them the

shole stretches out like a mat. In some settlements every married man has his own adornment for his idol; in other settlements only some of the men

have it, but the chief or captain al- ways has it. When many villages unite in order to celebrate some feast, each one comes with the little basket of

his idol.

In front of each one they nail his wide or narrow, long or short board, according to the wood they had. Those living near the ocean have the widest

boards because they make use of some pines that grow near the beach.

These boards are highly prized by the barbarians because they cost a great deal of time and more labor than it is easy to imagine, when we consider

that without any other implements than sharpened stones or flints they have to rough- hew split the trunk, hew it out and polish it until it gets as

thin as aboard."

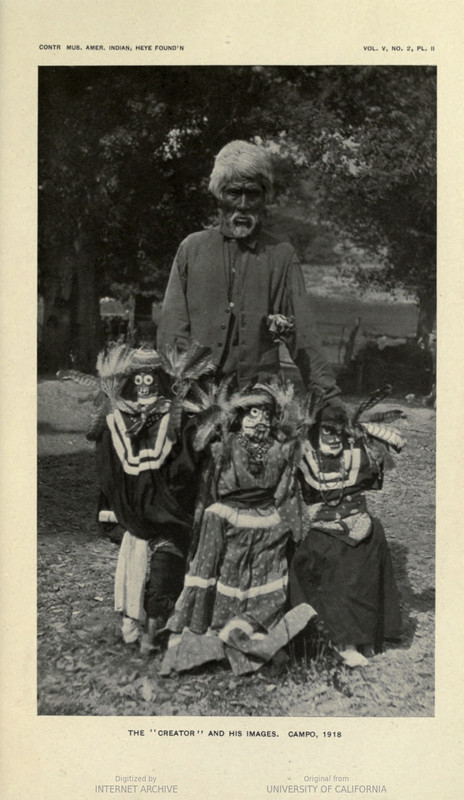

Here is a description of the Diegueno version of the ceremony for some insight. 'The Diegueno Ceremony of the Death Images '

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t8nc5w...

[Edited on 8-1-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Unfortunately the Krmpotic translation of Consag is known for not being very good.

"carried away or concealed their household utensils together with the idols that they are wont to keep in a house or bower apart from the town"

It actually says "by chance" the image house and the images inside were left behind when the people fled. This may seem odd but if you read the

Diegueno version you will understand why, and why the people started coming back. It must have been quite traumatic.

[Edited on 8-1-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

If you can create double spaced paragraphs every few lines will make reading things like this greatly easier! 👍

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Done

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Thanks.

That we can read something from the 1750s is pretty amazing.

The details of water sources and people found during his expeditions were so important for future travels and mission sites.

I am not seeing anything about image burning, however. Perhaps because I am on my cell phone with its small screen?

The entire book with Consag's two expedition diaries and other letters, is online for all to read. Link is with the photo of the book, in the History

Books page at VivaBaja Books.

Here: https://vivabaja.com/baja-books/3/

(Go to the 11th image)

[Edited on 8-1-2023 by David K]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by David K  |

I am not seeing anything about image burning, however. Perhaps because I am on my cell phone with its small screen? |

The link I posted at the end, 'The Diegueno Ceremony of the Death Images ' , explains what Consag was seeing. When people die they are still around

but a bit lost, confused, and angry because they no longer have a body. The image burning ceremony is held to finally send them away to the north.

The Images are bodies for the dead to inhabit during the ceremony.

Both the Kiliwa and Diegueno myths that explain the reason for the ceremony contain references to secondary burial, something the Kiliwa and Diegueno

did not practice. The Cochimi on the other hand did, suggesting the ceremony actually originated with the Cochimi or perhaps even south of them.

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Interesting... a bit theoretical, however, is it not? Thank you.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

The Consag Expeditions post

Is in the July 2023 Baja Bound Bulletin thread link...

Baja Bound Bulletin

If you use a cell phone to view...

You won't see the captions for the illustrations...

I will add them here:

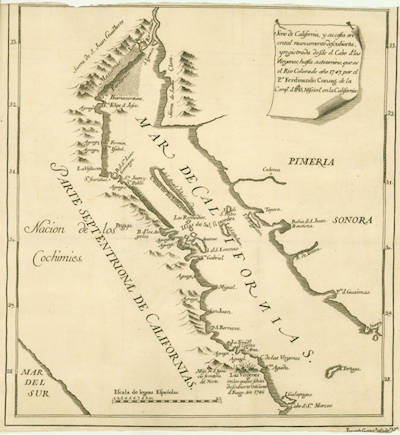

Map showing Mission de San Ignacio at the center-bottom, plus three proposed missions that are labeled as empezada (started). To the west is Mission

de San Juan Bautista Emp. (empezada). To the northwest is Mission de los Dolores del Norte empezada. To the northwest of Dolores is Mission S M Mag.

(Santa María Magdalena) empezada.

Map drawn by Consag in 1747 following his sea expedition. Note that his latitude figures are one degree too high. View Larger

Don Laylander's map with Cochimí placenames.

Discovered by Padre Consag on his 1753 expedition, this year-round stream of water at Calamajué was undrinkable. The 1766 mission was built on the

upper left edge of this photo. Seven months later, this mission was moved about 30 miles north.

Don't want to click the Baja Bound link?

Here is the text of my article...

History tells us about many explorers of the New World. The Jesuits explored on land and sea hoping to find places to build new missions, as well as

helping the Spanish King expand his empire, and bringing more Native people into the church. In 1697, the first mission colony was founded at a place

called Conchó by the Natives who lived in the area. We know that location today as Loreto.

In 1703, Fernando Consag was born in Croatia under the name Ferdinand Konscak. At the age of sixteen, he joined the Jesuits. In 1723, following years

of study and training, Consag was ordained into the priesthood. In 1730, Father Fernando traveled with a group of other Jesuits across the Atlantic to

North America. Once he was in Veracruz, Consag was assigned to serve in distant California. The hard journey there was so he could assist Padre

Sebastián Sistiaga at Mission San Ignacio. Sistiaga was losing his assistant, Padre Sigusmundo Taraval. In 1733, Consag arrived at his new post.

Padre Taraval had been assigned to the new mission of Santa Rosa de las Palmas.

By the 1740s, the Jesuits had founded fourteen California missions. Only one of which had been abandoned, the mission at Ligüí. These missions were

all in the southern half of the peninsula, a place many still believed was an island. In the fifty years from the founding of Mission Loreto, they did

not build any further north than the 1728 mission of San Ignacio. Consag, in addition to assisting Padre Sistiaga, traveled to other missions to

assist their padres. Consag was at Mission Guadalupe in 1744 when its church wall fell and killed many people inside.

The efforts to maintain these missions and feed the neophytes were massive. Bringing supplies across the gulf from Mexico was extremely difficult with

many ships lost in the crossing. A land route to California was the only hope to ensure safe communication with the mainland missions. That is if

California was not an island! The peninsular nature of California had been established by earlier explorers of the Gulf of California, yet

cartographers continued to show it as an island.

Even with supply difficulties, the glory of a Jesuit California was huge, and benefactors promised large sums of money to help the missionaries. They

probably believed (or were told) that sponsoring a mission would guarantee an easy path to heaven. Thanks to this financial support, Jesuits began

construction of proper stone churches to replace adobe and palm thatched ones. Loreto, San Javier, Mulegé, San José de Comondú, and San Luis

Gonzaga all had beautiful stone-block-walled churches, built between the 1740s and 1760s.

In 1746, Spain wanted to secure California from foreign powers as well as find a land route to there from Mexico. The Jesuit Provincial, Cristóbal de

Escobar y Llamas had ordered the California Jesuits to settle the question of island vs. peninsula. The Padre Visitador Juan Antonio Baltasar selected

Padre Consag for this question, an excellent choice. He had been exploring the regions beyond San Ignacio where three proposed missions were planned:

San Juan Bautista in the Santa Clara mountains; Santa María Magdalena in the north; and Dolores del Norte between San Ignacio and Santa María

Magdalena. All three proposed missions only existed on paper but have caused speculation about the three being ‘lost missions.’ Consag began

baptizing Natives on his explorations for a future Dolores del Norte mission.

Padre Consag’s 1746 sea expedition examining the east coast of California and finding if it is connected to North America, would seem to be the

final say in this question. Consag’s voyage of discovery began at the small inlet of San Carlos with four small open boats, called canoas.

Accompanying him were six Spanish soldiers, a small number of his neophytes from San Ignacio, and a group of Yaqui Indians from Mexico. They set sail

on June 9, 1746, and traveled by day and came ashore each night. Let me share a few entries to illustrate the level of detail which Consag enters into

his diary:

On July 16th is an interesting entry where Padre Consag writes that they arrived at Bahía San Rafael and discovered hot springs by some white rocks

that were covered at high tide. The hot water comes up through the sand here and other places along the same sandy beach for half a league (approx.

one mile). When covered by high tide, the water is “tinged with red mixed with faint blue.” Some friendly Natives took them to the San Rafael

Aguage (a fresh water source). Consag writes, “Not far from the beach is a large pond, and near it a well, which when cleansed affords good

water.” This describes the lagoon near the late Pancho’s San Rafael beach camp.

July 20-22: Consag at Bahía de los Angeles had some ‘issues’ with the Natives there. Interesting reading!

July 23: The expedition reached the Bay of Remedios (today it is better known as Bahía Guadalupe). Consag describes it in great detail.

The next few days, Consag describes Isla Angel de la Guarda then the arroyos, littered with palm leaves, which caused the expedition to seek water,

and they found a pond some distance up the sandy wash.

July 28, they arrive at Puerto Calamajué and named it San Pedro y San Pablo, for the anniversary of those apostles. The next day, they pass Punta

Final and detail the “larger bay” and the harbor on its north end, “separated by a narrow channel” which Consag names Bahía de San Luis

Gonzaga. They spent three days there but after digging a well nine feet deep, could not find water.

The diary continues with amazing details on the shoreline and the Native rancherias (settlements or family groups). Consag reaches the Colorado River

and sails up it on July 18, 1746. They spent several days studying the delta so by July 25, he was confident that California was not an island.

Not having found any suitable locations for a mission on his 1746 sea expedition, a second expedition, by land this time, would look to the far north

on the western slopes of the peninsula. This second expedition began on May 22, 1751, at La Piedad, a place Consag says was already picked to be the

next mission [the future Santa Gertrudis] and where he had baptized many Natives for tentatively named Dolores del Norte. In 1751, Consag wrote that

the spring at La Piedad had failed, and a well was some distance away. The expedition included five soldiers and a “sufficient number of natives on

foot.”

An interesting passage is found on June 2: “We finally followed a small stream, the water of which looks like liquid salt. In its extremity there is

a great quantity of white marble transparent like onyx. We proceeded in search of another stream, but we found ourselves very high in the Sierra

already and the passage so beset with craggs that it was necessary to retreat.”

The diary again gives much detail of the land, the people and the difficulties suffered. Many times, the expedition’s meals were provided by

roasting agaves and collecting the abundant shellfish. Many water sources were found but often were salty. A map locating the diary’s Native

placenames would be most interesting and beneficial to see their route. Don Laylander does show five of them on his map of Cochimí placenames.

Potential mission locations were mentioned in the diary. None were ever utilized. Padre Fernando Consag, and the 1751 expedition, returned to La

Piedad on July 7 and 8. Here at La Piedad, Mission Santa Gertrudis was officially founded on July 15, 1752. The year between the two events was for

preparation, building, and learning the Cochimí dialect by the new California Jesuit, Padre Georg Retz. Consag’s baptized Dolores del Norte

neophytes, were now members of the new mission. Consag trained Retz at San Ignacio for the year leading up to the new mission’s founding.

Fernando Consag was not satisfied with the mission-site possibilities he had seen on these two journeys. A third expedition would be needed to

investigate the eastern slope of the peninsula, inland from the gulf coast. In the Spring of 1753, fifty-year-old Consag was ordered by Padre

Visitador Augustín Carta to make a third expedition to find suitable mission sites. When Consag traveled, he only brought a walking stick and a

section of canvas to serve his needs for the day and for the night. He was one tough padre!

The diary from the third expedition was apparently lost. We know from other works that saw in the diary; Padre Consag traveled in June and July of

1753. That he was received well at Bahía de los Angeles this time. The Cochimí men even cleared a road for him into the mountains. The expedition

reached a point approximately parallel to Bahía San Luis Gonzaga. No mention is given to the oasis that would become Mission Santa María in fourteen

more years, even though some modern writers claim Consag found it. The wide arroyo of Calamajué was discovered, but its water was heavily tainted

with minerals and undrinkable. When Padre Linck came to Calamajué in 1766, recent rains apparently diluted the stream, fooling the Jesuits, for it

was decided to build a mission there later that year, a mission that could not grow any crops. No other location visited by Consag in 1753 was

promising.

They had not seen the hot spring location called Adac on the route they took. Its existence would later be disclosed to Padre Retz at Santa Gertrudis,

in 1758. Padre Fernando Consag, who was then the Superior of the California missions, desired to build the new mission of San Francisco de Borja Adac.

Sadly, his health and then death on September 10, 1759, would prevent that wish. Consag will be remembered as one of the Jesuit’s and Baja

California’s great explorers.

References:

The Life and Works of the Reverend Ferdinand Konscak, S. J., 1703-1759, An early missionary in California by MsGR. M. D. Krmpotic, 1923

The Missions and Missionaries of California, Vol. 1. Lower California (Second Edition) by Fr. Zephyrin Engelhardt, O. F. M., 1929

The History of [Lower] California by Don Francisco Javier Clavigero, 1786, translated into English by Sara E. Lake, 1937

Black Robes in Lower California by Peter Mastern Dunne, S.J., 1952

A History of Lower California by Pablo L. Martinez, 1960

The Apostolic Life of Fernado Consag, Explorer of Lower California by Francisco Zevallos, 1968

Jesuit Relations, Baja California, 1716-1762 by Ernest J. Burrus, S.J., 1984

Antigua California, Mission and Colony on the Peninsular Frontier, 1697-1768 by Harry W. Crosby, 1994

Baja California Land of Missions by David Kier, 2016

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

The ultimate place of origin for the ceremony is theoretical yes .

The purpose and myth behind the ceremony is well documented from native informants. There are several records of the ceremony.

[Edited on 8-3-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Kalvalaga

"On the 14th we reached the place inspected before and we stopped on a slope in front of the settlement. There are on its declivities some small dug

wells of brackish water and at the foot the large ravine (arroyo)." 28°53'34"N 114°20'56"W

⁷

"On the other side there are some other small wells in which there is more and better water. To this the mounts were taken and the majority of our men

too, provided themselves with this water."

28°54'02"N 114°21'44"W

[Edited on 8-3-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

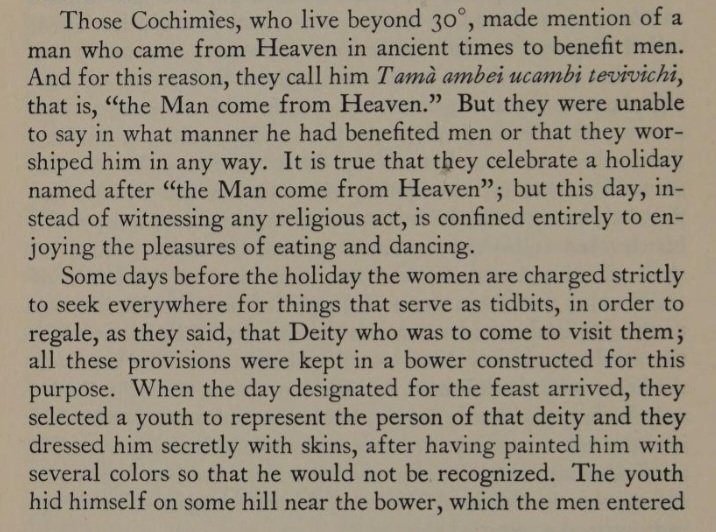

A different but related Cochimi ceremony.

These geoglyphs, on hills, several around Agua Dulce, published by Ewing.

The following English translation of this passage is from Clavigero. The passage originates in Del Barco. It doesn't appear in his section covering

ethnology and linguistics, instead it appears right after the chapter on moving the cabacera of Santa María. He says it comes from the priest of the

most northern

missions. The Jesuits had the latitude for San Borja at 30° I believe, maybe David can confirm.

[Edited on 8-8-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

From the Kiliwa (the Cochimis northern neighbors) 'The war between the gods ' recorded by Meigs. This isn't a minor episode, this moment is the

pinnacle of a long saga. Death had already been introduced to the world but there were certain divine beings who could make it so themselves and

others could continue to go about in a body as if they were still alive. This moment is the end of that.

"At last he found the boy. He said, "He is in the sky. The dead one has a shirt. One cheek is painted jamák jál'jáu (jamák, with hand on face, all

covered; jál'jáu, green), and the other is painted jeg jál'jáu (see fig. 18, a). He grasps a war club (jípáčmilsú pǎkáu, war club made of

one piece of wood; sál [eru]mé, 'he grasps'). He has down on his head (tesa', a tuft of feathers worn on the head). This is his clothing"

The father was also seeing his son in the sky: "Yes. It is true, what the hechicero says. But some things he says are not true.' But he thought this,

only, and said nothing. The hechicero said, "I can do nothing. I cannot bring the dead one back from the house where he is."

Then Pokipai remained thinking. He made a cigarette, and sat think- ing, "How am I going to be able to bring him down?" Then he blew out a cloud of

smoke. The smoke went directly east and passed by Wey Mijak (in a song). The smoke went farther and farther up toward the north (where Mexicali and

Calexico are) by a white hill. And the smoke went all around until it entered the house of Maikwiak (in the sky). Then the smoke entered the house of

Maikwiak to the place opposite the center of the row of dead (fig. 18, 6). (The dead all sat on that side, and there was a sort of glass on the other

side through which everything could be seen. Things can be seen when the smoke, amá'ijiñam, is as a flash of lightning, and everything can be seen

for just a moment.)

The smoke made a path to God's house. The house has a crotch (me- táimá isecan) in place of a door. Nobody can enter, but the spirit of the shaman

who wants to see things can look through the crotch. But it could not see well, because the crotch was just on a level with its eyes. (All the dead

are on the south side of the house, covered with mats of reed called cuánáy like those in the cave.) Pokipai put the smoke there so that things in

the house would be lighted and could be seen. (Many details are missing from the story, especially what is said in the songs, but I can't explain

well, and I forget some, too. Some of the dead are in God's house in the sky, others are in the hills, others under the ground.) Then all could be

keen well. Pokipai began to sing a song which said, "I find myself like a dead person. (And the song continued about hills, and the clothes of the

boy, and many things.) Now you are going to sit down. Now you are going to get ready. Now you have to go." He (the dead child) went down the path,

which was made of many things. He went down to the first sky, when Pokipai said, "Meñufkuñamá" (i)jáu mól jachap él kuá'ipái(v)" (the name of

that sky). There he could be seen going down. He went down to a hill called Mejé(u)wey (east of here).

Pokipai finally brought the child into the tiwa'. Everybody could see him inside. Then said a seer (Joá'kuñamá") in the tiwa', "It is not just that

a dead man should be here like a living man. (Because he ate all the food that had been set in the back of the house for visitors; not just the savor,

as the dead should, but the entire food.) If many people come today or to- morrow, there will be nothing for them to eat?" (The food is put in little

clay bowls for eating, for food is given to all comers.) Then said Pokipai, who was thinking about many things, "It is true." Then he began to sing,

saying, "Tobacco. Green smoke. I take it. I smoke. I blow smoke. It is my right. I order it."-Metáiltomákachái ("tobacco"), nipóyke ("smoke"),

mílsú ("green"), něpíau ("I take it"), echú ("I smoke"), akám ("I blow smoke"), iú jamát ("it is my right"), epá ("I order it"). (These are

the words of Maikwiak, not like those of the Kiliwa. All the songs are in these other languages.)-The song is finished, the boy was no longer there;

he vanished"

To get a better idea read How Maikwiak Was Born (page 69) and The War Between the Gods (page 78)

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x030370150

[Edited on 8-3-2023 by Lance S.]

[Edited on 8-6-2023 by Lance S.]

[Edited on 8-14-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Kiliwa Nipumjos aka "Dios Chico". Linck describes these among the Cochimi north of San Borja in a letter to the treasurer. He says they are carefully

carved statues, not works of art yet not altogether crude and primitive. One hand held an entwined snake and the other held a trident.

This "Dios Chico " could be the image for the dead god boy (see the war between the gods recorded by Meigs) that runs down the hill in the man who

comes from heaven ceremony. The dead god boy in the myth can no longer continue going about in a body as if he were still alive. This image was

not burnt like the ones in the image burning ceremony but was kept in a cave when not in use.

[Edited on 8-3-2023 by Lance S.]

[Edited on 8-5-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

It's all about the moment death becomes permanent and inescapable.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by Lance S.  | Kalvalaga

"On the 14th we reached the place inspected before and we stopped on a slope in front of the settlement. There are on its declivities some small dug

wells of brackish water and at the foot the large ravine (arroyo)." 28°53'34"N 114°20'56"W

⁷

"On the other side there are some other small wells in which there is more and better water. To this the mounts were taken and the majority of our men

too, provided themselves with this water."

28°54'02"N 114°21'44"W

[Edited on 8-3-2023 by Lance S.] |

This is very interesting... How did you find the sites or come to realize they could be the same as Consag wrote?

Thank you!

On your San Borja latitude question: Yes, the Jesuits were one degree too high. San Borja is nearer (a little south of) 29° North Latitude not 30°.

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

The first important clue is the location of the Manila galleon wreck. Meigs placed Kalvalaga farther north, up near El Rosario. That may be why

Laylander places up near there on his map. In order for that to be true the Manila galleon would have to be much farther north than it is. Aschmann

had a dissenting view, he actually correctly guessed the vicinity of the wreck fifty odd years before it was found. He placed Kalvalaga somewhere

west of Punta Prieta.

The second important clue is Lincks 1766 diary which states Keda (Codornices) was the furthest north Consags expedition went. That can only be one of

the two groups Consag sent out to explore from Cienega/Kadazyiac (San Andres). He sent one group to explore east, to Codornices, and another north

to where they had seen smoke, Kalvalaga.

The current name gives it away. Two places with water, Los Ojitos.

[Edited on 8-6-2023 by Lance S.]

[Edited on 8-6-2023 by Lance S.]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Fascinating!

Have you shared this with Don Laylander? He is a member of my BajaMissions Facebook group and we email.

Congratulations on making history interesting and informative.

Thank you.

|

|

|

Lance S.

Nomad

Posts: 231

Registered: 2-16-2021

Member Is Offline

|

|

Thank you.

I assume it's been considered by others especially after the wreck was found.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65453

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by Lance S.  | The first important clue is the location of the Manila galleon wreck. Massey placed Kalvalaga farther north, up near El Rosario. That's why

Laylander places it there on his map. In order for that to be true the Manila galleon would have to be much farther north than it is. Aschmann had a

dissenting view, he actually correctly guessed the vicinity of the wreck fifty odd years before it was found. He placed Kalvalaga somewhere west of

Punta Prieta.

The second important clue is Lincks 1766 diary which states Keda (Codornices) was the furthest north Consags expedition went. That can only be one of

the two groups Consag sent out to explore from La Cienega (San Andres). He sent one group to explore east, to Codornices, and another north to where

they had seen smoke, Kalvalaga.

The current name gives it away. Two places with water, Los Ojitos.

|

Can you tell me where in Aschmann's book is the talk about Kalvalaga and the Manila galleon? Page # or which chapter, please. I have the 1967 reprint

and it lacks an index.

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2 |

|