| Pages:

1

2

3 |

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

The Founding of La Paz, Baja California Sur, Mexico

With the approach of May 3rd, we arrive at a date in La Paz history that I think is strongly misrepresented by local officials.

The pages below are from something I’m working on that I wanted to share with the three of you who really, really (and I do mean really) care

about the foundation of La Paz. It is quite long because I’m of those who believe that a historic perspective is necessary to really understand

something—that, and because I love history.

The Founding of La Paz

On the 3rd of May, 2012 the municipal government of La Paz will be sponsoring the celebration of the 477th anniversary of the founding of our fair

city, which would make it one of the oldest European settlements in the Americas.

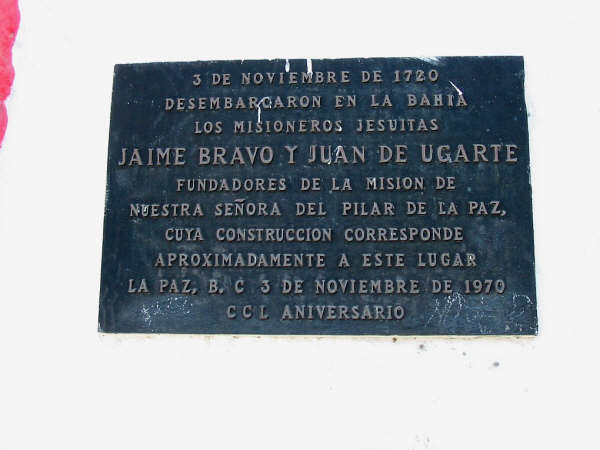

However, a short distance north of town along the scenic coastal road that winds it way out to Pichilingue, the remains of a monument built by an

international organization in 1970 commemorated the 250th anniversary of the founding of the city. If one "does the math," it becomes obvious that

something is amiss as both of these dates cannot be correct. Furthermore, many who have studied the peninsula's history disagree with both dates for

the founding of the city. The following is a summary of the various efforts made to colonize the shores of the Bay of La Paz.

The Discovery of Baja California

In 1533 Hernan Cortez sent a two-ship expedition to explore and map the northwest coasts of Spain's flourishing colonial effort in America. The two

ships became separated early in the voyage. One headed out into the Pacific to discover some unpopulated islands of little consequence before

returning to Acapulco empty-handed, not the result that Cortez—who had financed the venture out of his own pocket—was hoping for.

Things went far worse for the other ship. Crewmen who were unhappy with the harsh treatment of their captain killed him while he slept. Under the

direction of the ship's pilot, Fortun Jimenez, the mutineers put ashore those who didn't support their actions then set sail to the northwest to put

some distance between themselves and the scene of the crime. After some time, the fleeing men stumbled on what they thought was a large island. And so

it was that Europeans discovered the peninsula of Baja California. Although we know the year of this discovery, its date has been lost to history

because of these acrimonious circumstances.

The rebels are thought to have settled on the shores of the Bay of La Paz since Cortez is said to have found signs of their passage during his attempt

to colonize the peninsula two years later. What is certain is that their stay there was short. Soon after their arrival, the Spaniards noticed that

pearls were abundant in the area and began pressuring the natives—later known to Spaniards as the Guaycura—to dive for them, causing resentment among

the locals. When the newcomers also began forcing themselves on Guaycura women, their men decided that enough was enough and pounced on the camp.

Twenty one of the mutineers—including Jimenez--were killed. Eighteen of them managed to escape to the mainland, where they told of discovering a place

with fertile, well-populated lands with vast quantities of pearls for the taking. Although Cortez wasn't pleased by the results of the expedition, he

was encouraged by the survivors' tales and decided to lead the next expedition himself.

The Case for 1535

On May 3rd, 1535 Cortez arrived at what is known today as the Bay of La Paz. Following the custom of some Spanish explorers of the era, he christened

the place Santa Cruz (Holy Cross) and claimed it in the name of his king (May 3 is the Day of the Holy Cross on Spanish calendars). The man who had

humbled the preeminent powers of Mexico was looking for new challenges—and the riches they would bring—and the fantastic stories of pearls and

fertile, heavily-populated lands to the northwest of Nueva España intrigued him. Since pearls were of major commercial interest at the time, Cortez

brought two survivors from the ill-fated expedition of 1533 to ensure that they would locate the fabled Island of Pearls.

Spanish authorities required that all conquests be part of an effort to Christianize and settle any newly subjugated lands so Cortez recruited over

300 men and 37 of their wives for the endeavor. Cortez also rounded up some 130 horses to help overcome any resistance from the local population.

Livestock and other animals were also acquired for breeding purposes at the new colony. In mid-April 1535 Cortez and around 100 men and forty horses

and some cattle and other farm animals embarked at the mainland port of Chiametla to initiate the first of two planned trips to the peninsula. The

ships reached the peninsula’s coast on May 1st and dropped anchors in the waters of the Bay of La Paz two days later. After unloading, the three ships

were dispatched back to Chiametla to bring over the remaining colonists and supplies. But God did not bestow her favor on the effort to colonize the

peninsula and troubles soon emerged.

Two of the three ships sent back to bring over supplies and colonists were blown off course by one of the storms that frequent the Gulf and ran

aground on the mainland. The ship that did manage to get through had more people than provisions, so only contributed to the already-desperate

situation. Cortez took command of the recently arrived ship and returned to the mainland to search for the two missing ships. He found both while his

own pilot managed to run them own boat aground. After arduous efforts, Cortez and his crews managed to float and repair the three ships before

sweeping up and down the coast in search of more supplies.

Unfortunately, Sinaloa, where the ships had run aground, was under the governorship of Nuño de Guzman, one of Cortez’s chief competitors and a known

enemy of his. The governor issued an order for non-cooperation with the ships’ crews, which made it more difficult to find providers and drove up the

prices of what they were able to obtain. When they finally returned to the colony, they learned that the colonists had resorted to eating their horses

and other animals. Even so, some of the colonists had died of starvation.

Whatever else he may have thought during his brief sojourn on the peninsula now called California (although it was still thought to be an island),

Cortez must have been bitterly disappointed when he realized he'd been duped. Although pearls were abundant in the new land, there were no large

cities or the wealth they implied. In fact, there were no permanent settlements at all, which allowed the natives to disappear into the countryside

the instant Spanish boots hit the beach--likely a reaction triggered by their experiences with the mutineers two years earlier.

Worse, without the native agriculture that the tales of large cities implied, the colonists were reliant on an environment they were clueless in

knowing how to exploit. Procuring enough food to ensure the colony's survival became an impossible task. No mention is made of productive agricultural

efforts, which for the Spaniards of that time usually required something in extremely short supply in the southern peninsula: a river nearby.

After about a year of futile efforts to make the colony thrive, Cortez was recalled to the mainland by the viceroy to attend to matters of more

concern to the Crown. It seems likely that he would have been relieved to have such an opportune reason to abandon the failing enterprise and save

face (although he was known for keeping meticulous records of his movements and accomplishments, Cortez was unusually quiet about his time spent on

the peninsula). Francisco de Ulloa, Cortez's trusted aid, was left in charge of the distressed colony when the Conquistador left for Acapulco. A short

time later, Ulloa and the rest of the survivors were also given orders to leave the peninsula and head to Acapulco, no doubt much to their relief. The

unforgiving environment of Baja California succeeded in doing what the mightiest nations of pre-Hispanic Mexico only dreamed of; it drove the

Conquistador of Mexico back into the sea from where he had come.

No one knows for a fact where Santa Cruz was located. Some have thought it was at the site of the present-day private tourist resort named Las Cruces,

opposite Cerralvo Island. Others speculate that the deep water port described by Cortez, Ulloa and others matches the topography of the port at

Pichilingue, ten miles north of present-day La Paz. Still others insist the colony was located where La Paz sits today.

Then Came the English…

Although there were no serious attempts to colonize Baja California during the next 60 years, it wasn't because of a lack of interest from the Spanish

Crown. Two events in the late 1500s underscored the need to settle the peninsula with Spaniards. The first alarm sounded in 1578, when Francis Drake

became the first English freebooter to enter the waters of the Pacific Ocean, which had seemed like a private Spanish lake until then. Drake sacked

and pillaged the Spanish communities along his way up the west coast of the Americas and captured one of the coveted Peruvian Silver Galleons. His

voyage is thought to have taken him to San Francisco Bay and perhaps beyond, an area he claimed for his queen and country and named New Albion. He

then headed out across the Pacific to eventually round Africa and return home to a hero's welcome as England's first global circumnavigator—and a very

wealthy entrepreneur.

The urgency to colonize the peninsula turned to panic eight years later when a second Englishman, a 22 year-old self-financed captain named Thomas

Cavendish, duplicated Drake's sacking-and-pillaging-of-the-colonies routine along Spain's Pacific Coast, and then some.

On November 4, 1587, Cavendish became the first to achieve the ultimate dream of every swashbuckler of the era when he captured the Santa

Ana, one of the famous Manila Galleons returning to Acapulco from the Spanish trade center in the Philippines. These treasure ships were always

overloaded with goods from throughout the Orient and could be counted on to have severely weakened crews onboard, a result of being without fresh

provisions for several months. Approximately three weeks before the galleon arrived off the Cape Region, Cavendish dropped anchor at the eastern tip

of the Baja California peninsula at Agua Segura (Sure Water), at the estuary at present-day San Jose del Cabo. A more ideal place to await a passing

galleon coming from Manila is hard to imagine. That coastline is a good fair weather anchorage, fresh water was available nearby and the Pericue

people Cavendish encountered were happy to trade fruit, fish, pearls, animal hides and trinkets for manufactured items while the English awaited the

arrival of their prey. And best of all, there were no Spanish settlements anywhere near to interfere.

The Vizcaino Visit

The capture of the Santa Ana once again emphasized the need for a Spanish presence on the peninsula. In early October of 1596 the celebrated

Spanish navigator Sebastian Vizcaino left Acapulco bound for the peninsula in a three-ship colonizing expedition paid for by the Royal Treasury.

Vizcaino knew first-hand the importance of the undertaking; he had been onboard the Santa Ana when it was seized by Cavendish and had lost a

fortune in merchandise to the English pirates.

After reaching the tip of the peninsula—where Vizcaino undoubtedly remembered being put ashore after the capture of the Santa Ana nearly a

decade earlier—the expedition headed up into the Gulf, paralleling the shore while searching for a suitable place to settle. The shelter of the Bay of

La Paz once again was a beacon to the passing ships, but the exact date seems to be a well-kept secret. When the natives warmly greeted them, Vizcaino

chose the name of La Paz (The Peace) to commemorate the friendliness they had found there. They soon realized that they had settled at the same site

Cortez had chosen, since they could still trace the outline of the plaza de armas (the town square) the Conquistador of Mexico had laid out

some 60 years prior. The natives, who were known as the Guaycura by then, possessed metal tools that the colonists also attributed to Cortez’s failed

venture.

The Guaycura took to the padres immediately and seemed to enjoy the rudimentary religious indoctrination they received. They brought their visitors

fruit and fish and gifts of pearls and trinkets they had made. What the natives didn’t like—at least the men—was the attention that Spanish soldiers

paid to Guaycura women, saying that they’d like the padres to stay but wished that the soldiers would go away.

In spite of great anchorage offered in the Bay of La Paz, Vizcaino must not have been convinced that he had selected the best place for a colony since

he soon sent a ship with orders to explore and map the coast further north and report back. When the ship returned—sans 18 men, some of whom were lost

in a skirmish with locals while others had drowned attempting to flee back to the ship—to report nothing but sterile coastline for some 100 leagues

north, Vizcaino realized that the colony would be unable to sustain itself on the peninsula, dooming it to failure. The hostilities encountered by the

ship sent up the coast were also taken into consideration when he decided to pull up stakes just two months after leaving Acapulco. Vizcaino likely

didn’t want to participate in a repeat of the Cortez experience on the peninsula.

Although they reported rain in October—which reminded some of the Spaniards of Castilla—from their accounts it seems likely that the expedition’s time

on the peninsula was during one of the region’s cyclical droughts, which can last several years and have a history of dislodging would-be settlers.

The peninsula's environmental challenges once again proved too much for non-natives to overcome.

Pearling expeditions, whose members were not always the most exemplary practitioners of European etiquette, were the principal visitors to the Bay of

La Paz during the next eight decades. The Guaycura living along the shores of the bay returned to their practice of avoidance whenever possible.

The Atondo Fiasco

Although several exploratory voyages were made during the intervening years, the next serious effort to place an official Spanish presence on the

peninsula didn’t happen until 1683, when the Bay of La Paz was once again selected as the place. It is a testament to how much a bay such as

the one at La Paz was valorized for the protection it offered to shipping that it continued to be selected for a settlement site in spite of having

such a history of warding off would-be colonizers—although the bay’s evident wealth in pearls undoubtedly influenced such decisions, too. The viceroy

of New Spain again opened the purse strings on the Crown's behalf to pay for what would be the third serious attempt to colonize California in the 150

years since its discovery.

The three-ship expedition was headed by Admiral Isidro de Atondo y Antillon and included the Jesuit missionary Father Kino, an unspecified number of

soldiers and sailors, and all of the supplies deemed necessary to guarantee a satisfactory outcome. After a voyage from the mainland that lasted a

grueling 74 days, the ships arrived at La Paz on April 5 and the settlers immediately set about building a town in the middle of a palm grove on the

beach with two good sources of fresh water nearby. A large cross made of a palm tree was erected on an adjacent hill.

The Admiral, aware of the negative effects that poor treatment of the native people could have on the colony’s chances for survival, gave strict

orders for his men to be on their best behavior and implemented a code of conduct governing their dealings with the natives, especially their trade

relations.

For five days, the colonists saw nothing more than the footprints of the locals and smoke in the distance while they busied themselves building the

usual fortifications the Spanish used in such situations. Although the Spaniards couldn’t see the natives, the natives were watching them. The

Guaycura could tell from the activities at the new camp that these fellows had an agenda different from the one of the usual pearling expeditions they

saw and took umbrage at the intrusion of their ancestral lands. When they finally showed, they came fully armed, appeared hostile, and made it clear

that the newcomers weren't welcome to stay in that region of the peninsula.

Although the colonists tried hard to convince the natives that they came in peace, bribing them with manufactured items—which they initially refused

to take from the hands of the Spaniards, making the Europeans place gifts on the ground—and food in a land where it was almost always scarce, the

situation didn't change for the better. Much distrust existed on both sides. When a native shot an arrow at a Spaniard, causing no harm, the Admiral

decided he had to address the act aggression and shackled the offender in public as an example to the other Guaycura. If the desired effect was to

coward the locals into docility, it didn’t work. The natives became increasingly restless and defiant.

The Admiral—who had already had his men demonstrate to the locals the more damaging results of Spanish weapons on inanimate objects—decided it was

time to show the natives the effects of their weapons on human bodies. The Spaniards offered to feed 16 or so Guaycura who were still hanging around

the camp. Once the natives were sitting in a group on the ground and enjoying their sudden good fortune of a free meal, the Spaniards opened up with

their fire arms, killing 10 of their visitors and wounding the rest, who escaped to spread the word of this rude reception. The colonists would know

no peace for the remainder of their stay on the Bay of La Paz. Their fear was evident when the majority of them refused to consider Atondo’s proposal

to send their remaining boat to search for supplies, which would have left them with no means of escaping back to the mainland in a hurry. Running

out of provisions and with a certain mutiny on his hands if he dared to send his remaining ship to search for more, Atondo had no choise but to

abandone the enterpise, much against his own and Father Kino's personal wishes (Father Kino recorded some disgust at the demonsrated cowardice of the

soldiers--but then, he was a Jesuit, and they were known to welcome martyrdom). But neither gave up on their colonizing effort. After a short trip to

the mainland to replenish their supplies and round up the two missing ships, they returned to the peninsula and settled at a place north of

present-day Loreto and christened it San Bruno. But that colony, too, failed to take hold and soon California was once more European-free.

A Date With Destiny

At this point, it’s convenient for the flow of this saga to leave the chronological sequence of events and skip ahead just a bit.

In 1713 a ship anchored off Espiritu Santo Island to exploit the island's now-famous pearl beds, which had become famous among pearlers on the

mainland. Soon after their arrival, the Europeans were approached by several canoes manned with Isleño (Islander) natives from the nearby Island of

San Jose. Such contacts weren't unusual, for the Isleños weren't members of the Guaycura Nation and didn’t fear foreigners. Although they inhabited

islands of the lower Gulf that were offshore of Guaycura territory on the peninsula, the Isleños belonged to the Pericue Nation, which occupied the

southernmost tip of the California Peninsula and was hostile to the Guaycura Nation—something one would expect in a competition for resources.

The ship's crew, which numbered around 18, was soon playing host to their Isleño visitors, who were particularly interested in having the Spaniards

demonstrate the potential and range of their firearms. What the pearlers didn't know was that a year earlier, crewmen of another expedition had killed

two Isleños and their island-mates wanted revenge and had chosen this as the time and place. After gaining the trust of the Spaniards, the Isleños

took actions that resulted in the death of 17 of the 18 crewmen. The lone person spared was Juan Diaz, who was kept alive so he could sail the

captured ship. For a time, the Isleños proudly sailed their trophy about the Bay of La Paz. When the ship began to take on water, it was abandoned but

Diaz was spared to provide amusement for his captors and for his protective value.

Knowing that the Guaycura feared Spaniards, the Isleños used Diaz as a means of keeping them at bay while they exploited resources in Guaycura

territory. One day while the Isleños and Diaz were on peninsular shores the Spaniard made a run for it and managed to escape his captors, hiding out

in a cave until they left. He then tried to avoid being caught by the Guaycura, but they eventually tracked him down to his hiding place. To his

surprise, they took him in as one of their own. But after seven months of living among them, Diaz told his hosts that he was homesick and asked if

they'd help him get home to his family. They told him they would be sorry to see him go, but understood. The natives then took Diaz to a point jutting

into the sea and waited for a passing ship, which they flagged down with a bonfire on the beach. The ship sent a boat to shore, where Diaz was

waiting, alone. Before disappearing, the natives let him know that he'd always be welcome among them.

A First Step: The Jesuits Arrival On The Peninsula

The failure of the Atondo expedition opened the door for the viceroy to entertain all offers. So when the Company of Jesus, otherwise known as the

Jesuits, again offered to take up the challenge—at their own expense, no less—he accepted their offer. There was just one concession they asked in

return; that they be given complete control over all peninsular matters, including authority over their military escort. Although such authority was

never conceded anywhere else in Colonial Mexico, the viceroy must have felt he had nothing to lose, for he agreed to their terms.

In 1697 the first permanent European colony on Baja California—a Jesuit mission under the leadership of Father Juan Maria Salvatierra—was founded at a

place they named Loreto. Although the colony was some 140 miles up the coast from the Bay of La Paz, it was the all-important first step on the

peninsula. The Jesuits, unlike all previous colonizing efforts, counted on the impressive agricultural and cattle production of their mission network

in Sinaloa and Sonora. The generosity of the Jesuit missions on the mainland provided the needed relief so that the missions in California could get a

toehold. Within eleven years of their arrival, they had founded four other missions from which to Christianize the peninsula's natives.

In 1716 the Jesuits felt ready to tackle the Christianization of the Guaycura heathens living to the south and sent an expedition to the Bay of La Paz

to establish a mission. The effort was led by Father Salvatierra himself, and included a military captain, a couple of soldiers and several

Christianized Indians from Loreto. When the Spaniards and their native allies disembarked on the shores of the Bay of La Paz, the Guaycura did their

usual hasty retreat to the hills. Only this time, the Indians from Loreto gave chase, ignoring the calls of Salvatierra and the captain for them to

stop. Although the Guaycura men were able to escape, in what can only be described as a total lapse of chivalry, they left the ladies in their dust.

The natives from Loreto soon caught up to the women, who began throwing stones at their antagonists. Several of the women were killed by their

pursuers in the unfortunate encounter. Salvatierra figured that it would be pointless to build the settlement under the circumstances and the

expedition returned to Loreto.

The Jesuit Mission In La Paz

By 1720, the Jesuits were ready to give it another try at La Paz, evidently hoping that if the Guaycura couldn't forget, perhaps they could at least

forgive. A task force consisting of two expeditions was sent from Loreto to establish the mission. On the first day of November, El Triunfo de La

Cruz left Loreto to sail down the coast to La Paz while an overland expedition was sent under the command of Father Clemente Guillen to establish

a land link between Loreto and the new mission.

On November 4, Fathers Jaime Bravo and Juan de Ugarte disembarked on the shores of the Bay of La Paz. While they awaited the arrival of Guillen's

overland expedition, they busied themselves laying the foundations for the new settlement. As was their custom, the Guaycura were nowhere to be found.

After a week of waiting, the Spaniards sent out a scouting party to locate the missing people—whose tracks were everywhere—but had no luck. Other

search parties soon followed, with the same result.

Ironically, the first contact the new mission had with "local people" wasn't even with the Guaycura. On December 4, one month after the Jesuits

arrived, four canoes with over twenty Isleños, including several women, arrived from San Jose Island. Rather than a blessing, their presence was

ominous. The Isleños had only dared come ashore because of the presence of the Spaniards, a fact that likely only confirmed to the watching Guaycura

that the Spaniards were the accomplices of their enemies.

On November 6, after a grueling 26-day journey, Guillen and his group of explorers arrived at the site of the new mission. The Isleños returned to San

Jose a few days later, leaving the Spaniards and natives from Loreto alone on the bay's shore. During the day, the Spaniards continued to investigate

the distant smoke, only to arrive after the natives had cleared out. At night the Guaycura came close enough to the Spanish settlement to shoot arrows

at the animals brought from the mainland.

And so it went, until December 20, when another party left the camp on horseback to continue the search for their missing congregation. After two days

of riding, the Spaniards spotted a group of Guaycura, who immediately attempted to flee. With horses making the difference, the Spaniards quickly

overtook the natives. Realizing that they wouldn't be able to outrun the Spaniards, the Guaycura turned to face their pursuers with weapons drawn. The

Spaniards dismounted and tried to calm them with soothing words and gifts, but the Guaycura were having none of it. The situation was tense as the

Guaycura readied to do battle when one of them recognized one of the Spaniards, and gave out a shriek of happiness at the unexpected encounter. It was

their old friend Juan Diaz, the same man who had lived among them some seven years earlier. After much rejoicing, the Guaycura agreed to visit the new

colony. And that is how the Jesuits were finally able to overcome the native resistance to the Spanish presence on the shores of the Bay of La Paz.

In the beginning, the mission thrived and several more were opened south of La Paz. But the cultural changes imposed by the Jesuits on the Indians of

the Cape Region led some to resent their new neighbors. By the fall of 1735 the discontent culminated in the first of several native rebellions in the

region. By the time the revolt was squashed, two padres from the southernmost missions were dead along with several Christianized natives and three

soldiers, including one from La Paz. Things went much worse for the rebels when the Jesuits brought over Christianized Yaqui Indians from Sonora to

hunt them down and eliminate the threat. In the following years the natives rebelled several more times in the southern peninsula and the mission at

La Paz was closed temporarily a few times as a precaution. Although it was never attacked again, the missionaries and military escorts who lived at La

Paz during the following decade and a half led an uneasy life.

By the mid-1740s most of the indigenous people of the Cape Region had died. The mission at La Paz was permanently closed in 1749 and its remaining

converts were moved to the mission at Todos Santos, on the Pacific Coast. Although many rebellious natives were killed in the suppression of the

rebellions, the diseases brought in by Europeans were the biggest factor in the decimation of the southern peninsula's Indians.

The First Civilians Arrive On the Peninsula

In 1748, against the wishes of the Jesuits, the Spanish government granted Manuel de Ocio, a retired soldier from the Presidio at Loreto, a mining

concession in the mountains south of the Bay of La Paz at a place he named Santa Ana. It was the first civilian settlement on the peninsula and was

joined by a second one a short time later when Gaspar Pison was given a mining concession at nearby San Antonio in 1756. Their concessions stipulated

that none of the peninsula’s remaining native people were to be used in the mines, so Ocio and Pison brought in Mayo and Yaqui Indians from Sonora to

work them. Initially, the mining district had no impact on the Bay of La Paz. But as mining grew in importance, that changed.

By the early 1800s the mission system established by the Jesuits was in name only. Most of the natives, the sole raison d’être for a mission,

had died off and their lands had been taken over by the families of retired soldiers or immigrants from the mainland. The Southern Mining District

established by Ocio half a century earlier, however, was doing quite well and had become the most important economic activity on the peninsula.

Initially, the two mining communities were able to meet their needs locally. They operated their own cattle ranches to provide meat and cheese and the

hides needed in mining operations. They bought fruits and vegetables from the people working the former mission lands. But as the enterprises grew,

local production didn’t keep up with their needs so the miners became more outward-oriented. Most of their trade was with the Gulf ports on the

mainland, but foreign shipping also increased in important over time. At first, the district used three peninsular ports.

A thriving agricultural community had developed on the well-watered and fertile lands at the former mission site at San Jose del Cabo. Its location on

the tip of the peninsula also made it a popular watering stop for passing ships, so it would have been a natural choice as a port. But in addition to

being the most distant of the three from the mining district, its open anchorage offered no protection for shipping when the weather turned foul.

The anchorage that is closest to Santa Ana and San Antonio is Ventana Bay, which is some 20 miles east of the district. But Ventana Bay, too, offers

little protection from the strong winds that frequent there, winds that can complicate cargo transfers between ships and shore.

The Bay of La Paz, which has been considered by some as the finest port on either coast of the Gulf of California, is some thirty five miles north of

the old mining district. The bay offers excellent protection for shipping the year round. From mining officials' perspective, the port was perfect in

every way but one; it had no resident population to draw workers from. The natives had been absent since the mission closed in 1749 and the site had

remained free of permanent inhabitants. A soldier assigned to the mining district took note.

Juan José Espinoza

In 1811, as the struggle for Mexican independence was getting underway on the mainland, a retired soldier named Juan José Espinoza who had been

assigned to San Antonio was given a sitio (a measurement of land used for agricultural production) on the shores of the Bay of La Paz as a

reward for his services to the Crown. The sitio encompassed all of what today is the city of La Paz, and then some (the Jesuit mission ruins were

still visible and located within Espinoza's sitio). Among the stipulations in the land grant was one that mandated that Espinoza provide fresh produce

to ships calling at the port.

By the early 1820s, Mexico was celebrating its newly won independence. On the peninsula, a Mexican governor appointed by the newly-minted federal

government was running governmental affairs from the old capital at Loreto. Among the first problems he tackled were the complaints of ships' captains

of the lack of fresh provisions at the port of La Paz. The Espinozas hadn't been able to cultivate enough land to satisfy the demands of the

increasing numbers of ships bringing in mining supplies. After taking stock of the situation, the governor rescinded the exclusivity of the Espinoza

grant in 1823 and authorized others to settle and cultivate the lands surrounding the port. Espinoza's heirs mounted several legal challenges to the

governor's ruling over the ensuing decades, but lost them all.

La Paz has been continually populated since the issuance of the Espinoza grant. If one must celebrate the “founding day” of La Paz, that is the one

that seems the most appropriate. Its problem is that it’s too common, too ordinary—and who’s ever heard of Juan Espinoza?

[Edited on 4-25-2012 by Bajatripper]

[Edited on 7-25-2012 by Bajatripper]

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65452

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

This is a wonderful history story post Steve... Is this from a book, Internet or your own?

Thank you!

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by David K

This is a wonderful history story post Steve... Is this from a book, Internet or your own?

Thank you! |

There's the first one, two to go!

This is my compilation of the events taken from various books we have on the subject, most of them in Spanish.

PS I can't think of any serious writing I'd do in which I'd use the Internet as a primary source. Too unreliable a source.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65452

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by Bajatripper

| Quote: | Originally posted by David K

This is a wonderful history story post Steve... Is this from a book, Internet or your own?

Thank you! |

There's the first one, two to go!

This is my compilation of the events taken from various books we have on the subject, most of them in Spanish.

PS I can't think of any serious writing I'd do in which I'd use the Internet as a primary source. Too unreliable a source. |

An exception might be http://VivaBaja.com and specially http://VivaBaja.com/bajamissions

|

|

|

DianaT

Select Nomad

Posts: 10020

Registered: 12-17-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

It is good to see that someone who is relating these historical stories is reading about the history in Spanish ---- it gives more depth and

perspective to the stories.

The only good thing about the internet is that it has given easier access to some primary sources of history. While three people can read the same

primary sources and come up with three different versions of history, the original source is always the most interesting. It is not necessarily

unbiased, however.

Enjoyed reading your post.

[Edited on 4-24-2012 by DianaT]

|

|

|

Barry A.

Select Nomad

Posts: 10007

Registered: 11-30-2003

Location: Redding, Northern CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: optimistic

|

|

Excellent post, Tripper. Your style of writing is so enjoyable and interesting, relating the facts and history in a very easy-to-read and fun

manner. Fascinating 'read', for sure.

Very tough people back then-----both the Natives and the Spaniards.

Looking forward to your next offerings.

Barry

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by Barry A.

Excellent post, Tripper. Your style of writing is so enjoyable and interesting, relating the facts and history in a very easy-to-read and fun

manner. Fascinating 'read', for sure.

Very tough people back then-----both the Natives and the Spaniards.

Looking forward to your next offerings.

Barry |

OK folks, that's three. I'm satisfied. Any more are icing on the cake.

Thanks for your kind words, DianaT.

I'm particularly touched by your comments, Barry, considering our discussions in the off-topic section. It must have been light on the

liberal/communist/socialist agenda

And no, David K, with the stuff I'm interested in writing, I wouldn't use an Internet reference as a primary source for anything, even yours, as good

as it is. I guess that makes me one of those liberal elit snobs, without the money or the ivory towers.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65452

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Steve, can you help me with the original mission site of La Paz... Is it (from your research) about where the plaque is located?

GPS: 24°09'36.00" -110°18'59.4"

[Edited on 4-25-2012 by David K]

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by David K

Steve, can you help me with the original mission site of La Paz... Is it (from your research) about where the plaque is located?

|

The picture of the plaque you posted is one of the possible locations of the mission in La Paz. Others favor a site about two blocks E of there,

sharing some common ground with the Mercado Madero. This place has some support from me because an old Paceño I know worked on that site in the 1970s

when they were building the then-new Mercado Madero and mentioned to me that they came across some old foundations that he was at a loss to explain.

Another resource I have (all of these sources are in Spanish) says the mission was most likely located about five blocks south of those sites, around

calles Pineda and Belizario Dominguea/Madero. That author says that the only place that originally had the grove of palm trees the missionaries

mentioned was the shore of El Manglito, placing the mission at the Pineda location.

One of my stepfather's students did a search of the historic record during the 1950s and came up with a location somewhere around where that plaque is

located. If I come across it (it's here in the house somewhere), I'll take a closer look and let you know if I find out anything of interest to you.

It's another one of those local things that no one can be sure of. What is certain is that the location of the present Cathedral of La Paz

has nothing to do with where the old mission was at.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

BajaBruno

Super Nomad

Posts: 1035

Registered: 9-6-2006

Location: Back in CA

Member Is Offline

Mood: Happy

|

|

A nice piece of writing, Tripper. It sounds like La Paz has just missed celebrating its bicentennial! I'll be interested to read the formal version

when it comes out with footnotes and a bibliography.

Christopher Bruno, Elk Grove, CA.

|

|

|

El Vergel

Nomad

Posts: 197

Registered: 8-27-2003

Location: San Felipe - Puertecitos Rd., Km. 35 and Santa Mon

Member Is Offline

|

|

Thanks for this great post!

|

|

|

gnukid

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4411

Registered: 7-2-2006

Member Is Offline

|

|

Interesting how determined western society is to claim to have discovered existing societies and claim they are founded by European roots, whereas

that's certainly a stretch.

For example, one can interpret that Hernan Cortez efforts were quite minimal and hardly beneficial or critical to the successful development of La

Paz, the people or the historical traditions. He married an indigenous woman who was the critical negotiator and her child is therefore a meztizo.

This is not a criticism of the writing or work contributed here, why with such a long and fantastic history do historians insist on "defining a

moment" as the time of discovery? Often those moments are associated with murder. The whole historical writing process is often absurd.

Person arrives at a location, murders some people there, then we claim they discovered it.

A more realistic view might say that the area of La Paz has a long history, perhaps 30,000 years with Guaycura, Pericu and Islenos and a recent short

period of meztizo integration with input from people around the world.

La Paz is celebrating it's 30,000 year anniversary.

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by BajaBruno

I'll be interested to read the formal version when it comes out with footnotes and a bibliography.  |

Thanks for the encouragement, Bruno, and it's in the works, but unfortunately, it's on Mañana time.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

Jack Swords

Super Nomad

Posts: 1095

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: Nipomo, CA/La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

|

|

Very nice write up on the history of La Paz. When I took the photo David posted, it was the only site acknowledged as in the proximity. The nearby

buildings are very old, it's on a hill, but La Paz is very old. El Manglito's palms existed when the US occupied La Paz as evidenced by old drawings.

And, there is today flowing water running into the sea from that area. The old windmills on the site would also indicate that it could be a location

of one of the earliest settlements or the mission. Please post your findings if you are able to pin the site down. Great job!

Ever hear of the tunnels running through parts of town from the Cathedral? Always wanted to check it out. Good story tho.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65452

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Thanks Jack and Steve for the added details.

Since a mission would require a good fresh water supply (and a work force or 'souls to save'), a spring or creek would be a good indicator.

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by gnukid

Interesting how determined western society is to claim to have discovered existing societies and claim they are founded by European roots, whereas

that's certainly a stretch. |

Actually, gnu, this seems to be a condition inherent in all human kind. In my studies (to the PhD level in Cultural Anthropology) one thing that comes

through loud and clear is that people everywhere think they are "The Center of the Universe" and that all others are lesser creatures. Mankind has

ALWAYS had conflicts over resources, that will never change.

It just so happened that it was the people of Western Europe who first combined all of the knowledge and inverntions and discoveries made before them

and the firearms they designed with the Chinese invention of gunpowder into a machine of conquest that overtook the rest of the world (timing is

everything, baby!).

But if they hadn't had done it, it would have been the Chinese, the Moslems, or perhaps the Aztecs or Incas (the Maya were already out of the picture

by the time of the European breakout). For a good read on this subject, I'd recommend Eric Wolf's Europe and A People Without History.

| Quote: |

For example, one can interpret that Hernan Cortez efforts were quite minimal and hardly beneficial or critical to the successful development of La

Paz, the people or the historical traditions. He married an indigenous woman who was the critical negotiator and her child is therefore a meztizo.

|

That is precisely my point, gnu. Cortez left here a whipped, defeated puppy who had absolutely NO bearing on the history of this place--save for all

of the unrecorded deaths of local inhabitants from the diseases the Europeans brought. This whole anniversary thing is just a ploy for tourism

dollars. Note, we don't even have a statue of Cortez (something that is VERY RARE anywhere in Mexico, in spite of the role he played in nation's

history), so how seriously do they really take this date? But it sounds soooo nice to say that our community has so much history, when, in fact, it's

a pretty new city on the peninsula.

Now, about doña Marina (La Malinche), Cortez never married her, he had a child with her (don Martin) out of wedlock (Cortez was already married to a

woman of good Spanish stock and as a good Catholic, wouldn't have dreamed of leaving his wife) and then passed her along to one of his lieutenants,

whom she did marry. Based on the historic record, and what others have said, I doubt that Cortez could have conquered Mexico without her. She was an

amazing woman and in no way was a traitor to the Aztecs (She was Aztec by birth, but sold into slavery to non-Aztecs, so it becomes a question of "who

betrayed whom?"). If people knew her complete story, I think most would admire her, too.

| Quote: |

This is not a criticism of the writing or work contributed here |

None taken. I can clearly distinguish between attacks on the messenger and attacks on the message. I welcome your discussion of history, one of my

chief interests.

| Quote: |

why with such a long and fantastic history do historians insist on "defining a moment" as the time of discovery? Often those moments are associated

with murder. The whole historical writing process is often absurd.

|

Another point I was making. And please note, there isn't an exact date of Espinoza's occupation of the site, which you should approve of. It wouldn't

have been a very significant event.

| Quote: |

Person arrives at a location, murders some people there, then we claim they discovered it.

|

Yeah, you're right. But, unfortunately, that's just the way it's always been. It is the victors who get to write the "His"-story. Comes back to that

whole "human nature" thing I was getting at--although, if I had to wager an educated guess, it would be that the Liberals stay home and it is the

Republicans who go running out there trying to take everyone else's wealth away. Only now, they employ Free-Market Capitalism as their

weapon-of-choice

| Quote: |

A more realistic view might say that the area of La Paz has a long history, perhaps 30,000 years with Guaycura, Pericu and Islenos and a recent short

period of meztizo integration with input from people around the world.

La Paz is celebrating it's 30,000 year anniversary. |

You are absolutely right again, gnu. Trying to uncover that history is something my step-father, William C. Massey, my mother Bajalera, and others

have been doing for some time now. Unfortunately, the natives made it a bit more challenging by not leaving a written record we could all read up on.

Archaeology is a long, slow process.

The latest to bear the torch is Harumi Fuchita, a Japanese archaeologist who has done considerable work out on Espiritu Santo Island, trying to

establish a 40,000 year window of occupation for the region.

http://www.innerexplorations.com/bajatext/an.htm

http://www.pcas.org/Vol34N4/5Fujita.pdf

Again, gnu, thanks for the feed back

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by Jack Swords

The nearby buildings are very old, it's on a hill, but La Paz is very old. El Manglito's palms existed when the US occupied La Paz as evidenced by

old drawings. And, there is today flowing water running into the sea from that area. The old windmills on the site would also indicate that it could

be a location of one of the earliest settlements or the mission. Please post your findings if you are able to pin the site down. Great job!

Ever hear of the tunnels running through parts of town from the Cathedral? Always wanted to check it out. Good story tho. |

Thanks for your words, Jack. Just a couple of points to your post.

Although some of the buildings in downtown La Paz look old, there is not one single colonial-era building standing anywere in the city since there

weren't anything but seasonal fish camps on the shores of the bay at the time Mexico declared its Independence from Spain (1810). The Espinoza land

grant dates from 1811.

Wind mills were quite common throughout the city, hence its "sobrenombre" (nickname) found in many books: "Ciudad de los molinos" (Windmill City, or

City of the Wind Mills for those who are nit picky). I know older Paceños who live in what was then the outskirts of town (around the Arturo C. Nahl

Stadium) who remember fetching water by the pail from the properties around them that had wind mills and storage pilas (one of these was located at

the Escuela Simon Bolivar across from the Tienda Ley on Cinco de Mayo). They bought the water by the centavos-per-bucket.

The city's first water system was started in what today is the core of the down town, sometime in the 1920s or so (I might be off a decade either way,

but can find it in a ref if anyone cares) and went from the city plaza area down Madero Street towards the Esterito, probably bringing public water to

the first Hospital Salvatierra (built in 1892). Without running water, there wouldn't have been a need for drainage, so why the "old" church (as the

Cathedral was known first and which dates from around 1870s) would have need for tunnels isn't something I'm familiar with nor have I heard of such

tunnels. But that certainly doesn't mean they don't exist and I'd be interested in anything you find out.

As for springs, keep in mind that the alluvial plain where the core of La Paz is located is transected by five arroyos, each of them an underground

stream for the water running between the sierras behind our city and the waterfront. In rainy years, springs would have been common along them (as I'm

sure you know from your many trips into the Baja boonies). The mission could have been located near any one of them.

All we know from the Jesuit record is that there were two springs near the site (one with better water than the other), that it was up on a mesa (not

in an arroyo, duh!), there were palm trees at the site, and that it was an "escopeta corta" (an early short muzzleloader) shot from the shore of the

bay. One thing that argues against the Manglito-is-the-only-place-that-had-palms is a line from Pablo Martinez's Historia de Baja California

Edicion critica y anotada that says when Padres Jaime Bravo and Juan de Urgarte began exploring the bay's shoreline from a boat, they saw several

(varios) "esteros, carrizales (reeds, a good indicator of fresh water) y palmares (palm groves)." That would cast doubt on the Manglito site being the

single possibility.

And, as for current "water flowing into the sea" in the Manglito area, here's some more-recent local history. The big funny-looking building with the

large pipes running through it on the corner of the first block on the right after Alvaro Obregon leaves the waterfront (heading south) is called "El

Carcamo"--which means, among other things a hole or ditch. When we lived in that neighborhood in the 1960s, that place ALWAYS stunk because it's a

pumping station in the sewage-collection system of the city. Back then, it always had malfunctions and spewed untreated water into the bay around

there. That is why there were still huge hachas (the animals that produce scallops) off the Manglito even then when the rest of the city's waterfront

had been picked clean. Everyone who lived around there knew you didn't eat things that came from that area. I'm not saying that's still the source of

any "fresh water" running into the bay there, just a possibility.

Of course, if I were on a hunt for the missing mission, I'd also be interested in those old foundations my ancient Paceño friend mentioned coming

across under the Mercado Madero. He also mentioned seeing something that could have been interpreted as "old tunnels" at the same place. But those

would have been on the other side of the Arroyo 16 de Septiembre, which would have been impractical to connect to the Cathedral side of the arroyo.

Next time I see him, I'll have him re-brief me on that, it's been many years since we had that conversation and I can't remember the details.

A disclaimer: my writings on this are based on quite a few books on the subject, each of which have variations in details, names, etc. of the same

events they supposedly recount. I go with what sounds most plausible, but keep the other stuff in mind always.

Again, thanks for your interest.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

DianaT

Select Nomad

Posts: 10020

Registered: 12-17-2004

Member Is Offline

|

|

I love reading the different views as that is what history is all about---very few actual facts, and lots of perspective. Every one has a bias and

there are so many sides to every historical story. Even the original primary sources are biased.

For me, it is what attracted me to major in history and one of my favorite classes was historiography.

Bajatripper---keep on digging, keep on writing, and keep on discussing your point of view and how you came to that view.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65452

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

"A disclaimer: my writings on this are based on quite a few books on the subject, each of which have variations in details, names, etc. of the same

events they supposedly recount. I go with what sounds most plausible, but keep the other stuff in mind always."

Sounds like the way I do my mission notes in presenting the history of them. Just when I think I understand the history of them, something different

will pop out and catch my eye! It makes a great hobby for me, the history of (Antigua) California!

|

|

|

Bajatripper

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3152

Registered: 3-20-2010

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by David K

"A disclaimer: my writings on this are based on quite a few books on the subject, each of which have variations in details, names, etc. of the same

events they supposedly recount. I go with what sounds most plausible, but keep the other stuff in mind always."

Sounds like the way I do my mission notes in presenting the history of them. Just when I think I understand the history of them, something different

will pop out and catch my eye! It makes a great hobby for me, the history of (Antigua) California! |

And it's always good to keep it in mind when discussing history with others, keeps one from being proven the fool too often.

There most certainly is but one side to every story: the TRUTH. Variations of it are nothing but lies.

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3 |

|