| Pages:

1

2

3

4

5

..

9 |

elbeau

Nomad

Posts: 256

Registered: 3-2-2011

Location: Austin, TX

Member Is Offline

|

|

I often just eat instant butter gritz with water. I never like it as much with milk.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

How about some more thoughts on the rock-pile location? I posted the entire letter from Henderson in hopes someone will read it differently than I...

or to validate we are searching in the correct west flowing wash.

My first choice was Arroyo B, but PaulW went in there last week, coming over into the B Valley from the north. He found an unpassable watefall with no

obvious solution. Henderson (read his words above) did not indicate anything that impossible sounding.

So my second choice is Arroyo A... only Phil with TW found a dam in a narrow section near the Arroyo Grande junction and a need for a ladder to get

over it. On the satellite images it seems there is a way to climb around on the north...?

There is just one more west flowing arroyo, that originates on the divide coming up from The Model A park location (Arroyo Arrajal). It is a bit south

of Arroyo A.

I was hoping the vertical cliffs described by Henderson at the junction of the rock-pile wash and Arroyo Grande would be the golden clue as to which

wash to hike up... A few months ago, I sent in (requested) TW with Phil to look for that cliff face... to determine which of the washes looked like

it. That is when TW took all the photos and GPS waypoints... except Arroyo B... and nothing jumped out at him from what Henderson wrote.

So, please... more Nomad eyes for this joint expedition of discovery!

|

|

|

elbeau

Nomad

Posts: 256

Registered: 3-2-2011

Location: Austin, TX

Member Is Offline

|

|

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

What no fountain of flowing water like at Mission Santa Isabel? Thanks elbeau!

Edit: Just GE your waypoint: That is on top of a mountain, not in the arroyo canyon/ valley... They saw it while walking down the wash, no mountain

climbing.

It was on a bench above the arroyo (a mesa-like appendage) and they could not see distant peaks (Borrego, etc.) from it, just the valley dropping to

the west.

[Edited on 3-24-2015 by David K]

|

|

|

elbeau

Nomad

Posts: 256

Registered: 3-2-2011

Location: Austin, TX

Member Is Offline

|

|

You didn't zoom in enough:

Henderson mistook the brickwork for a simple "rock pile"

|

|

|

elbeau

Nomad

Posts: 256

Registered: 3-2-2011

Location: Austin, TX

Member Is Offline

|

|

I'm not advocating a single point, just a general area:

|

|

|

TMW

Select Nomad

Posts: 10659

Registered: 9-1-2003

Location: Bakersfield, CA

Member Is Offline

|

|

Henderson mentions trees blocking his view. Maybe we should scan the Bing images and see where the trees are. That may be a clue on where they were

unless there are trees everywhere.

|

|

|

elbeau

Nomad

Posts: 256

Registered: 3-2-2011

Location: Austin, TX

Member Is Offline

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by TMW  | | Henderson mentions trees blocking his view. Maybe we should scan the Bing images and see where the trees are. That may be a clue on where they were

unless there are trees everywhere. |

yes, but he also says something about the fact that the trees were later cut down by logging activities.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

He mentioned the ironwood tree cutters had not ventured that far south yet. Mesquite trees perhaps?

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

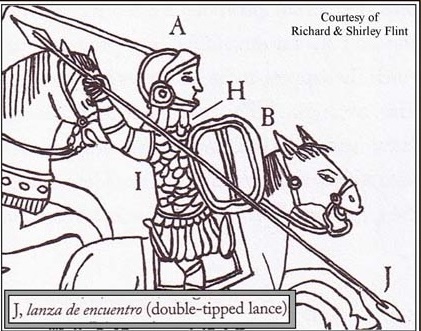

What did Melchior Diaz look like, how did he die?

A typical Spanish captain in Mexico and the type of lance that may have killed Diaz...

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

OK, that helps to know... joining me after Ken's Pole Line Road run:

Tom (TMW)

Karl (Fernweh)

Vern (El Vergel)

Harald (4x4abc)

Anyone else coming out to camp with us, a week from tomorrow?

[Edited on 3-29-2015 by David K]

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

After Ken's Pole Line Road run:

Tom (TMW)

Karl (Fernweh)

Vern (El Vergel)

Harald (4x4abc)

Anyone else coming out to camp with us, a week from tomorrow?

|

|

|

4x4abc

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 4454

Registered: 4-24-2009

Location: La Paz, BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: happy - always

|

|

where in the letter is it mentioned that they realized that they had gotten too far south in AG?

Harald Pietschmann

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Not too far south in AG (Arroyo Grande), but to begin their hike... after they realized they were too far to walk to the Tinajas or Palmitas hills

where they hoped to find blue palms. Possibly they didn't realize they were too far from them until they were at the divide (top) of the Sierra Pintas

and could see the other ranges or the Sierra Juarez for reference?

Henderson wrote other letters to Pepper/Desert Magazine and in Choral Pepper's telling of the story, she has some of those notes about the purpose of

the hike. Of course, those stories from Pepper's pen are not as exact as the letter from Henderson I shared here.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

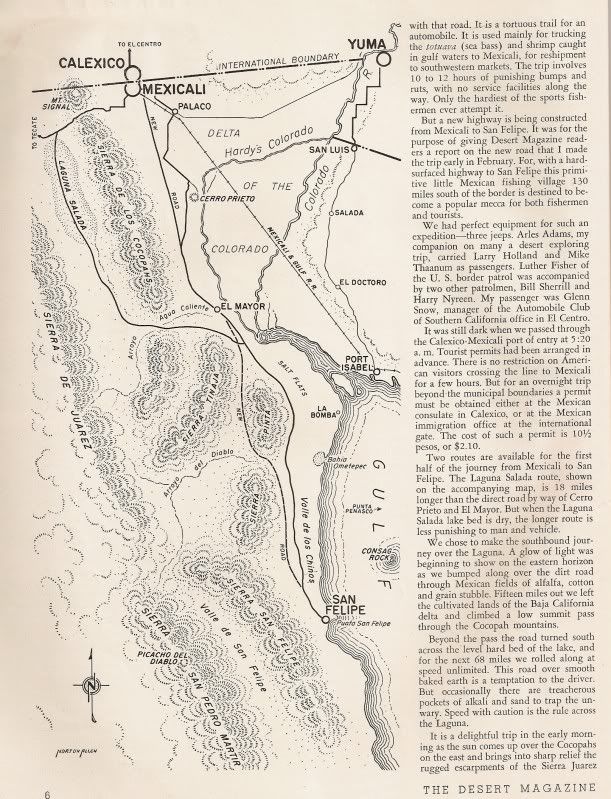

May 1948 Hwy. 5 under construction...

The location of the old road is just east of the new highway route (dashed line) in the area 35 miles north of San Felipe where Henderson says they

headed west to the base of the Sierra Pinta to begin the hike.

|

|

|

PaulW

Ultra Nomad

Posts: 3113

Registered: 5-21-2013

Member Is Offline

|

|

Could it be that the dashed road went over Pinta pass? Now days a rough passage. Who knows maybe back then the pass and approach from either end was

smoother with lots of fill that mother nature has removed?

Old maps are neat

PW

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

I think it is just the way the map maker is showing the new route as it is inside or west of the hills from the sand dunes to La Ventana and again

from La Ventana to El Chinero. The dashed line is representing the paved (to be paved) highway route.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Quote: Originally posted by David K  |

Not too far south in AG (Arroyo Grande), but to begin their hike... after they realized they were too far to walk to the Tinajas or Palmitas hills

where they hoped to find blue palms. Possibly they didn't realize they were too far from them until they were at the divide (top) of the Sierra Pintas

and could see the other ranges or the Sierra Juarez for reference?

Henderson wrote other letters to Pepper/Desert Magazine and in Choral Pepper's telling of the story, she has some of those notes about the purpose of

the hike. Of course, those stories from Pepper's pen are not as exact as the letter from Henderson I shared here. |

Here is the last version of the story written in 2001 by Choral Pepper for her final book 'Baja Missions, Mysteries and Myths':

-------------------------------------------------------------------

THE MYSTERY OF DIAZ' GRAVE

The story of Diaz' grave constitutes a classification all its own -- part history, part mystery, part myth. It will not remain that way forever,

though, if Los Angeles Police Department member Tad Robinette succeeds in his quest.

Upon reading my early Baja book, Robinette got caught up in the challenge of delegating immortality to the neglected hero Melchior Diaz. So in 1994,

putting his military and law enforcement training to test, he set out to settle the Diaz question once and for all.

The explosive history of Diaz' grave first came to my attention through a letter from the late historian Walter Henderson while I was editor of Desert

magazine "explosive" because it refutes several hundred years of fallaciously celebrating Padre Eusebio Kino as the first white man to set foot on the

west shore of the Colorado River. It was that chapter in my book that ignited Robinette's interest.

Baja Califorina's true first European visitor to the northern sector was Melchior Diaz, a beloved Spanish army captain dispatched in 1540 by Coronado

to effect a land rendezvous with Fernando de Alarcon, whose fleet was carrying heavy supplies up the Gulf of California to assist in Coronado's

expedition in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola.

It was during the depression of the early 1930s that Walter Henderson and his southern California companions cranked their Model A Ford roadster

through the rock arroyos of the unpaved road that led toward San Felipe, a Mexican fishing village about 125 miles south of the border at Mexicali. At

a spot a few miles beyond a window-shaped rock formation known as 'La Ventana', they unloaded their camping gear, filled their canteens from a water

tank in the rear of the car, and set out by foot.

On other of their frequent weekend safaris into Baja, if the Ford hadn't drunk too much of their water, they often camped overnight while searching

for old Spanish mines, Indian arrowheads, or whatever else adventure produced. Sometimes they found the powerful horns of a bighorn sheep arched over

its bleached and sand-pitted skull. At other times they heard the screeching wail of a wild cat or caught the fleeting shadow of a mule deer high up

in the Sierras. If a covey of quail flushed from a sparse clump of desert greasewood, they knew that water was nearby. Sometimes they found the

spring; most often they did not. Water is elusive in this rugged, raw land and rarely does it surface in a logical and accessible spot.

But on this cool day in April they were lucky. The Model A had behaved well and used less water than usual and they had managed to drive as far as the

foot of the Sierra Pintos with only three punched tires. Henderson had long fostered a yen to find a way into a canyon oasis he had heard about from

another man named Henderson (Randall, the founder of Desert magazine) who had described an oasis where native blue palms rose above huge granite

basins of water stored from mountain runoffs after storms.

As it turned out, they had hiked too far south. Baja California was only crudely mapped in those days and the Mexican woodcutters who supplied

ironwood for ovens to bake the tortillas of Mexicali and Tijuana had not yet been forced this far below the border, so there was no one to give

Henderson and his party directions.

Throughout the entire Arroyo Grande and Arroyo Tule watershed, they had found no sign of man -- just twisted cacti writhing across the sandy ground,

occasional stubby tarote trees, and lizards basking in the sun. On both sides of the wide arroyo up which they hiked, jumbled boulders stuck like

knobs to the mountainsides. In some areas the mountains were the deep, dark red of an ancient lava flow, in other sectors they were granite, bleached

as white as the sand in the wash.

When night fell, the hikers unrolled their sleeping bags, built an ironwood fire and fell asleep while watching the starry spectacle overhead. In

Baja's clear air, the stars appeared low enough to mingle with their campfire smoke.

At dawn, they brewed a pot of coffee, refried their beans from the night before, and tore hunks of sourdough from a loaf carried by one of the men in

his pack. There was no hurry. They had all day to explore as long as they kept moving back in the general direction of their car.

Late in the afternoon, after hiking across a range of hills, they came upon a curious pile of rocks set back a short distance from the edge of a steep

ravine. For miles around there had been no other signs of human life, neither modern nor ancient. The pile was nearly as tall as a man and twice as

long as it was high. The base was oval and the general shape of the structure resembled a haystack. The stones were rounded rather than sharp-edged,

and although the ground in the vicinity was not littered with them, Henderson and his companions figured that they had been gathered at great labor

from the general area.

They lifted a rock and turned it over. It was dark on the top, light colored underneath. The dark coating acquired by rocks in the desert is called

desert varnish. It is caused by a capillary action of the sun drawing moisture out of the rock. The dark deposit is left from minerals in the water.

In an arid region where rainfall is practically nil, desert varnish takes hundreds of years to form. The fact that these rocks were all coated by

desert varnish on the top indicated that they had remained in their positions for a very, very long time.

The men were tempted to investigate further, but it was the end of April, when the dangerous red rattlers of Baja California come out of hibernation,

so they contented themselves with speculation. The pile of rocks provided an inviting recess for these reptiles and the men were unarmed.

The rock pile stood close to the edge of a narrow ravine that twisted down from the hills over which they had descended. The site was not visible from

the surrounding country so it obviously was not intended as a landmark. That it was a grave, they felt certain, even though it was an unusually

elaborate structure for its isolated situation. Baja California natives have always conscientiously buried corpses found in remote countryside, but

usually the grave is simply outlined with a series of rocks rather than built up man-high like a monument. Whoever lay beneath this rock pile was

obviously revered by his companions who must have numbered more than a few in order to erect it.

Tilted against one end of the rock pile was an ancient piece of weathered ironwood nearly a yard long and as thick as a man's thigh. If a smaller

crosspiece had been lashed to it to form a cross, the addition had long ago eroded away. Ironwood, Olneya tesota, is a tall spreading tree found only

in washes of hot desert areas in the Southwest. Its wood is brittle, very hard and heavy, and it burns with a slow, hot flame. Mexican woodcutters

have all but depleted the desert of it in recent years, but during the 1930s when Henderson discovered the mysterious grave, it still was conceivable

that the heavy log could have been found close enough to drag to the graveside.

By this time the sun was falling low in the mountains behind them, so the men left the pile of stones and hurried on across the desert to reach their

car before nightfall. They never had occasion to return.

Two years later, however, the memory of the mysterious pile of rocks rose to taunt Henderson and continued to do so for the rest of his life.

The Narratives of Castaneda had been translated into English and a copy had fallen into his hands. When he came upon a passage that read " on a height

of land overlooking a narrow valley, under a pile of rocks, Melchior Diaz lies buried," he would have known immediately that he had found the lost

grave of this Spanish hero except for the fact that Pedro de Castaneda, who traveled as a scribe for Coronado, believed that Diaz was buried on the

opposite side of the Colorado River. However, Castaneda wrote his manuscript twenty years after it had happened and, since he was with Coronado rather

than with Diaz, his only authority was hearsay.

Melchior Diaz would have been completely ignored by history had it not been for the exploits of Fernando de Alarcon, who had been fitted out with two

vessels and sent up the Gulf of California by Viceroy Mendoza to support Coronado's land expedition. A rendezvous had been arranged at which time the

land forces were to pick up supplies that Alarcon would bring by sea. As Coronado and his forces moved north, however, their guides led them further

and further toward what is now New Mexico, and away from the Gulf where they were to meet Alarcon. When Alarcon arrived at a lush valley near an

Indian village far east of the Gulf, he established a camp and dispatched Melchoir Diaz westward with a forty-man patrol mounted on his best horses to

search for Alarcon's ships and make a rendezvous on the Gulf.

Diaz, traveling west, arrived about 100 miles above the Gulf on the bank of the Colorado River. There he learned from an Indian who had helped drag

Alarcon's boats through the tidal bore that Alarcon had been there, but was now down river and had left a note on a marked tree near where the river

emptied into the Gulf.

Diaz then marched south for three days until he came to the marked tree. At the foot of it he dug up an earthenware jug with contained letters, a copy

of Alarcon's instructions, and a record of the nautical expedition's discoveries up to that point.

Knowing now that Alarcon was returning to Mexico, Diaz retraced his steps up the river to what is now Yuma, Arizona, where he forded the river. The

trail through Sonora by which he had come north took his army far inland from the sea. In the event that Alarcon still lingered in the area, Diaz

hoped that by following down the West Coast of the Gulf his men might be able to stay closer to the shore and thus sight the ships.

Marching southward from the present Yuma where they had crossed the Colorado, Diaz and his men came upon Laguna de los Volcanoes, about thirty miles

south of Mexicali. It is from this point that the narrative grows vague, except for the historical account of Diaz' fatal injury and subsequent

burial.

The injury occurred one day when a dog from an Indian camp chased the sheep that accompanied his troops. Angered Diaz threw his lance at the dog from

his running horse. Unable to halt the horse, he ran upon the lance that had upended in the sand in such a fashion that it shafted him through the

thigh, rupturing his bladder.

References vary as to how long he lived following the accident. Castenada reported that Diaz lived for several days only, carried on a litter by his

men under difficult conditions over rough terrain.

Castaneda's report may be flawed. Not only did he write it twenty years after the fact, but his report was based on hearsay evidence since he was with

Coronado in what is now New Mexico and not along the Colorado with Diaz. A more modern historian, Baltasar de Obregon, wrote that Diaz lived for a

month following the accident. Herbert Bolton, the distinguished California historian, wrote that after crossing the Colorado River on rafts, Diaz and

his troops made five or six day-long marches westward before turning back after Diaz' injury.

If Bolton's information relative to the days that they marched is correct, and if Castaneda is accurate relative to the number of days Diaz lived

after the accident, Diaz is buried on the West Coast of the Gulf. If he lived for a month, however, his grave very likely lies on the Sonora coast.

This has never been established, although historians have searched fruitlessly for the grave on the East Coast of the Gulf for several centuries.

So convinced was Henderson that he had found Diaz' grave that he proposed an investigation to the Mexican consul in Los Angeles. He was received

politely enough, but turned away with the deluge of problems his suggestion encountered. He was told that to conform to Mexican law of that time his

search party must consist of from two to four soldiers, an historian with official status, a guide to show them where they wanted to go, a cook to

feed them, and mules and saddles so the Mexican officials 'would not have to walk or carry packs on their backs like common peons.'

In addition, the party would have to include someone to put the mules to bed and saddle them, a muleteer, and a security guard to protect Diaz'

helmet, leather armor, blunderbuss, broadsword, coins, jewelry and whatever else of value accompanied the skeleton in the grave. All this was to be

paid for by Henderson. A further stipulation stated that if the area turned out to be too dangerous or rough for the retinue involved, regardless of

expense incurred, Henderson would be obliged to call off the whole thing and turn back.

This, during those years of the depression, was out of the question for Henderson, or just about anyone else. In later years the rigors of such a trip

for Henderson were too great. Faced with those complications, he ultimately went to his own grave never having solved the mystery of Diaz, but haunted

throughout life by the memory of that mysterious pile of rocks. So Diaz sleeps, a neglected hero while Mexicans and Americans alike pay homage to the

prevalent belief that Padre Eusebio Kino was the first white man to come ashore on the west side of the Colorado River.

Now that Baja has come into its own as a popular destination, the present government might be more amenable to investigating the gravesite if it can

be found. According to Henderson's directions, a line drawn on the hydrographic chart of the Gulf of California from Sharp Peak (31 degrees 22 minutes

N. Lat., elevation 4,690, 115 degrees 10 minutes W. Long.) to an unnamed peak of 2,948 feet, NE from Sharp peak (about twelve miles away) will roughly

follow the divide of a range separating the watershed that flows to the sea. Somewhere near the center of that line, plunging down the westerly slope,

is a rather deep rock-strewn arroyo. On the north rim of this arroyo, and set back a short distance, is a small mesa-like protrudence, or knob of

land. There may be a number of arroyos running parallel. It is on one of these where the land falls away to the west that the rock pile overlooks the

arroyo. That was as close as Henderson was able to identify it on a map.

On one of my flights with Gardner in the 1960s, as we flew over land and water to Sierra Pinto, some thirty-two land-miles north of San Felipe, I

looked for a rugged ravine plunging down from the east side of Cerro del Borrego, a peak north of the present intersections of Highways 5 and 3, but

even the practiced eyes of pilot Francisco Munoz, who circled the area several times, were not sharp enough to etch a rock-covered grave out of the

colorless land. We did detect a dirt road about ten miles south of the La Ventana marker on modern maps that led into ruins of an old mine called La

Fortuna. That may have been where Henderson and his friends left their Model A Ford and initiated their hike.

So much for my treasure hunting competence!

But if any reader has ever doubted the efficiency of an L.A.P.D. cop, put your mind at rest. I have dealt with many treasure hunters, professional and

otherwise, but never have I encountered an equal in systematic persistence to Tad Robinette. Because of his intensive approach toward solving this

mystery, I shall recount it in detail as he reported to me.

Consistent with law enforcement training, Robinette?s modus operandi depended upon finding a good topographical map of an area relatively unmapped in

Henderson's day. After a series of long-distance calls around the United States, he finally located a store in North Carolina that stocked Mexican

topo maps. Within weeks, he had a collection of the best on the market. They were helpful, but obviously not the map that Henderson had consulted.

That one, Robinette determined, was probably a hydrographic map detailing the Gulf of California area north of San Felipe, since no detailed land maps

had been made at that time. The hunt then began for a hydrographic chart dated prior to 1950.

At about this time Robinette learned of a library in the basement of the Los Angeles Natural History Museum that contained old maps, including

hydrographic charts. Access, by appointment only, was arranged through the curator. Robinette arrived at his appointed time, was escorted through two

sets of double doors, and then turned loose in a basement room lined with volume upon volume of obscure books, old magazines, and stacked layers of

professional papers. He came upon a map section. No numbering system was used. The maps were haphazardly placed in drawers. By chance he found a small

collection of hydro maps dated between 1880 and1930. Among them was a copy of the very map used by Henderson denoting the same peaks and elevations.

Because nothing could be removed from that library, Robinette made notes to facilitate ordering a copy directly from the archives in Washington, D.C.

Three months later he possessed it.

He then painstakingly coordinated grids provided by Henderson's recollections superimposed upon modern detailed topo maps, geological surveys,

historical records of the Coronado expedition, and the projected distance for a day's march. This way he identified the most likely areas for

exploration.

It wasn't until 1998, however, that Robinette had accumulated enough information and time off work to convince him that a personal expedition was

worthwhile. Then, limited to two days that included the drives back and forth to Los Angeles, he got a good look at the 'lay of the land' south of the

border, but not much else.

His second trek, a year later, lasted for three days. This time he was rewarded by a fine rosy quartz vein, some spectacular sunrises, and a lot of

mountain climbing experience, but he did not find the grave.

Trek Number Three had to be postponed until the year 2000. Then, accompanied by his partner on the beat, Jamie Cortes, they attacked the landslides,

the defiles, and the cactus-covered lava mountains with vigor. During this trip they scoured the mid-section of the area Robinette had designated on

his map. On the last day they had an encouraging break. They had come upon a low range of rolling hills after descending from Arroyo Grande that

matched Henderson's recollection. But their time was up. The Los Angeles Police Department call to duty waits for no man.

So now we come to Trek Number Four. This time a third partner, Paul Dean, joined the hunt. Unfortunately, the promising 'low range of rolling hills'

failed to keep its promise.

After exceeding the limits of exploration, Robinette had initially projected on his maps, time ran out again. Tired and discouraged, the party was

straggling along a rough route in the direction of the car they had left behind when they came upon an unexpected pass that would have provided

Henderson's party, as well as their own, a lower and easier route back to the La Ventana area where their car was parked. This appeared at the end of

their allotted time, of course -- the destined fate of most treasure hunts! So they made a haphazard survey and left, promising themselves a return

next year.

As I have written before, I'll write again, "Adventuring in Baja is like a Navajo rug with the traditional loose thread left dangling. To finish the

rug would be to kill it. As long as it is unfinished, its spirit is still alive." Now who wants to kill adventure? Certainly not Tad Robinette. Nor do

I.

So, as Robinette ended his report to me, I'll end this book, "To be continued"

NOTES: As we can see from the 1967 letter, some details were omitted or changed. The Model A was driven to the base of the Sierra Pinta, west of El

Chinero. The next morning, they hiked to the top of the ridge, then down steeply towards Arroyo Grande. On this downward part, about noon, they found

the rock-pile (1/4 to 1/3 down). They continued to Arroyo Grande where they spent the night and returned to the Model A the next day, using a more

southern route at the base of Borrego Mountain.

I met Tad Robinette at Choral Pepper's home and he joined Nomad as 'Desert Ghost'.

It's time to find this rock-pile!

|

|

|

TMW

Select Nomad

Posts: 10659

Registered: 9-1-2003

Location: Bakersfield, CA

Member Is Offline

|

|

So Robinette never knew the real location of where Henderson went when he made his searches and if he did why did he leave his car at La Ventana. Also

why was an LA cop not able to take vacation time.

|

|

|

David K

Honored Nomad

Posts: 65445

Registered: 8-30-2002

Location: San Diego County

Member Is Offline

Mood: Have Baja Fever

|

|

Tad had never seen the Henderson letter before I found it in Choral's box of letters and photos. Like Bruce Barber, I also sent Tad the letter

considering all the effort he put into looking for the rock-pile, perhaps based on Choral's altered directions.

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

2

3

4

5

..

9 |

|