| Pages:

1

..

6

7

8

9 |

estebanis

Nomad

Posts: 279

Registered: 11-11-2002

Location: Stuck North of the Border. They won\'t pay me

Member Is Offline

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by Cypress

estebanis, Boil the whole duck till tender, debone, then mix with the cornbread along with all the rest of the ingredients you normally put into

dressing. You should have lots of stock left over from boiling the duck, mix that in as well. You want it soggy but not soupy. Put in the oven and

bake awhile. I might have to start duck hunting again.

|

That sounds great I am definatly going to make that this season. I will use my steamer probaly. I may make it with Coots also. The Coots at our club

are definitly edible. The Coots have a bad name from the ones eaten on the coast. which are eating some gross stuff. Here they eat the same food

sources as the ducks. My hunting partner calls me "CootBreath" I use that on one of my email accounts...

Esteban

|

|

|

Cypress

Elite Nomad

Posts: 7641

Registered: 3-12-2006

Location: on the bayou

Member Is Offline

Mood: undecided

|

|

Pompano, Thanks,

estabanis, Take Pompano's advice regarding the coots, you'll be wasting some good cornbread.

|

|

|

Pompano

Elite Nomad

Posts: 8194

Registered: 11-14-2004

Location: Bay of Conception and Up North

Member Is Offline

Mood: Optimistic

|

|

Wild Duck Recipe....Everyone's favorite..??

"Umm! I can’t believe this is WILD duck!....It’s so Good...and I thought it would taste like albatross!"

I've heard that a hundred times from visiting amigos. The following is our all-time favorite wild duck recipe, according to the various duck

hunters who have eaten lunches or dinners at my Duk Shak over the years.

I first ate a version of this recipe while hunting in Alaska years ago at a friend's duck heaven, but hopefully improved it by moving it to North

Dakota.

The method is quick, easy, and sure-fire - if you do it right. Warning and rule of thumb for any wild game: never, never overcook wild

game..and especially duck……If you overcook duck, it turns into "liver"!

So easy…just follow these step-by-step photos and instructions on how to cook wild duck so it is flavorful and juicy. Step into our kitchen, please!

"How To Prepare For Our Wild Duck Recipe"

A few very easy steps – to make a superb dish!

The duck breasts are cut into 2-bite-size pieces...

(...and if you use 'coot', you're on your own!)

For the marinade, you will need fresh garlic, shallots, rosemary, olive oil, and a coarse spice blend… like my favorite,

"Montreal Steak Seasoning".

Spin the veggies a few times in a food processor/blender. Combine chopped veggies, seasoning, and oil in a medium-size bowl until you have a moist

paste, not too thick and not too thin. Don’t fret about a measuring cup. You have a lot of flexibility here, so don't worry about the exact amounts.

Be generous with vegetables and spices.

Now add the cut-up duck to the marinade and let this sit for at least 30 minutes, up to 3 hours. If you can't cook the duck right away, store it in

the refrigerator. That’s risky, business, however…because the olive oil will solidify under refrigeration. Easy to fix though….you will have to let

the mixture come back to room temperature, so the oil drips off easily before you place the duck into a pan.

"Wild Duck Recipe – The Technique"

Pay attention here…This is the most important part!

Use a dry non-stick pan on the highest setting (or highest flame), and heat until it begins to smoke (or as is in my case, when your ceiling alarm

starts blaring.) Okay, it’s nicely smoking….so add a few duck pieces to the pan, and let them sear in place, for..oh.. about 1 minute or so. You may

want to turn the duck pieces on a paper towel before cooking - too much oil will lower the skillet temperature and prevent the meat from forming a

nice fine crust.

After a minute, turn the pieces over and sear for another 30 - 45 seconds. It all depends on the size of the breast strips, but you’ll get a feel for

it pretty quickly. The meat should be "rare" inside, “pink” as the carry-over heat will finish it to a "medium-rare" on the way from the kitchen to

the table.

Also be careful not to "crowd" the pan with too many duck pieces. You want to retain the highest possible heat throughout the searing process. Serve

these treats immediately if not sooner.

.

.

.

Sometimes I like to whip up some very easy-to-prepare "Duck Nachos", for a quick Snack at the Shak. I simply heat a platter of my favorite tortilla

chips in the oven - layered with shredded cheese and sliced jalapenos. The finished duck pieces go on top and along the sides of the platter. Serve

with some pico de gallo and guacamole, of course!

Well, the above was MY contribution…and here below Co-pilot chimes in with another recipe. Kinda so-so compared to my ducky stuff, but I’ll

humor her.

Grazie, tesoro. The Duck Appetizer Was Very Good –Mi piace…molto! But How about this for the main course? La nostra cena.

Yesterday, Co-pilot's main course was beef.. Black Angus Tenderloin with Bourbon Praline Pecan Sweet Potatoes and Buttered Broccoli. For

dessert we have a fresh baked slice of Lemon Tart torta with Whipped Cream. It was all delicious, naturally! Grazie, belladonna.

Humor Section:

A duck walks into a bar and says, "Got any bread?"

The barman says, "No, this is a bar, we don't have bread."

So the duck says, "Got any bread?"

The barman says, "No, this is a bar, we don't have bread. I just told you that."

"Got any bread?" asks the duck.

"No, we don't sell bread here... and if you say that again I'll nail your feet to the table!!!!"

The duck pauses then says, "Got any nails?"

"No," sighs the barman.

So the duck says..."Got any bread?"

Here's some more fun...and a quiz to boot:

Who might write the following on BajaNomads? I'm thinking of one nomad's writing style now. Just for fun, can you guess which nomad?

“If it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, we have at least to consider the possibility that we have a small aquatic bird of the family

anatidae on our hands.”

[Edited on 10-2-2011 by Pompano]

I do what the voices in my tackle box tell me.

|

|

|

Cypress

Elite Nomad

Posts: 7641

Registered: 3-12-2006

Location: on the bayou

Member Is Offline

Mood: undecided

|

|

Pompano, "Duck Nachos"! Good idea! According to the USFWS Duck Population Survey

for 2011 Mallards and Blue-Winged Teal are having a very good year. Green-Winged Teal are down? Good hunting! Thanks for the reports. Good idea! According to the USFWS Duck Population Survey

for 2011 Mallards and Blue-Winged Teal are having a very good year. Green-Winged Teal are down? Good hunting! Thanks for the reports.

|

|

|

Spearo

Nomad

Posts: 153

Registered: 11-30-2010

Location: Moscow, Idaho and Pescadero, BCS

Member Is Offline

|

|

Thanks for the photos and recipes Roger.

Your NoDak pics were great. I spend three weeks in South Dakota every year hunting pheasants and waterfowl. Nothing like the density and variety of

life you can find in the prairie pothole region. I've seen aerial photos from the Devils Lake area over the last couple years, kinda hard to believe.

Very rough on the local economy.

Think I'll go walk my bird dogs and reload some shells.

Were it not for the abdomen, man would easily reckon himself a god.

Friedrich Nietzsche

|

|

|

bufeo

Senior Nomad

Posts: 793

Registered: 11-16-2003

Location: Santa Fe New Mexico

Member Is Offline

|

|

Well, I was going to toss in a couple of my favorite recipes for duck and goose, but I see you guys using auto-loaders out there. Tsk, tsk. Even the

English chap? Nope. I'll have to hold off. I give out secrets only to SxS users.

Allen R

P.S. You guys still in tee-shirts. We haven't had any cool weather here either. Two years ago we'd already had some snow flurries.

|

|

|

Cypress

Elite Nomad

Posts: 7641

Registered: 3-12-2006

Location: on the bayou

Member Is Offline

Mood: undecided

|

|

bufeo, Was taught to let 'em gather up in a bunch, then cut loose with my single barrel. Killed 5 Mallards with one shot. Wasn't hunting for sport.

More bang for the buck and they sure were tasty.

|

|

|

bufeo

Senior Nomad

Posts: 793

Registered: 11-16-2003

Location: Santa Fe New Mexico

Member Is Offline

|

|

Ahhhh, Cypress. We were taught by the same 'folk'. We mustn't hijack Pomp's wonderful thread here, but since we abide in the same state, albeit miles

apart, perhaps we should continue this discussion, or reminiscence of things past, to a personal meeting.

"...5 Mallards with one shot". My, that sure beats my "triple with two barrels" on opening day of dove season 2010.

Allen R

P.S. I should have picked up and left with that opening salvo.

P.S. #2 Pomp, please accept my apology for diverting your thread.

[Edited on 10-1-2011 by bufeo]

|

|

|

bonanza bucko

Senior Nomad

Posts: 587

Registered: 8-31-2003

Location: San Diego

Member Is Offline

Mood: Airport Bum

|

|

Wild duck tastes luck toasted goat turds unless it's soaked in horseradish and cooked in a Chicom restaurant for about a week.

Wild goose is good only if you mix it with mushroom soup after marinading it in booze for days and days.

I have given up duck hunting (kinda): Here's the deal about that:

You get outa bed with a warm and cute woman (wife) at 0300 and then drive a hundred miles through the fog to a duck "club" (house trailer in a swamp

with a very smelly outdoor john and no running water and yesterday's coffee) that costs you $2000/year.

Then you get in a boat with a wet dawg and three other lunatics and motor out to the blind in the frigid dark while the wet dawg hits you in the mouth

with his tail and the lunatic in the back at the engine steers looking aft with the lunatic in the front with the flashlight (last year's batteries)

yells to him how to keep from going aground in the toollies. You go aground in the dark and use up all of last year's cuss words and bust an old oar

getting off after the batteries die and the wet dawg hits you in the face again and licks your nose and ears too....bad breath.

Then you climb up into a wet and smelly duck blind in the dark...more dawg tail in the mouth.....and wait for the little buggers to come zipping by at

about 200 knots just before dawn...that's the nice part. You shoot at them and, if you're like me, you miss about 10 times for one hit. The ammo is

Bizmuth because the f(*&*^*) feds have decreed that lead is "toxic" to ducks and can't be used to shoot at them....the approved alternative is

steel shot but that wrecks your expensive shot gun...so you use Bizmuth shot..... Only problem with that is that the Bizmuth costs $2.75/ round so my

basic dead duck costs me about $30.

Good part of this is the yellow lab (name is Connie...no training but smarter than duck hunters) who dives into 30F water and swims into tullies to

fetch half dead ducks....more tail in the face but you are happy with that.

Then we motor back to the "club" and start recovery from the pneumonia caught in the blind and the dark. Since the ducks will taste like toasted goat

turds we take them to a Chicom restaurant in downtown SAC and tell them we'll be back with female (sane) supervision in about a month.

We come back and have a rousing dinner party with lotsa booze. The females all get indigestion from the f%%$ duck which still tastes like toasted

goat turds but now with lotsa Chicom hot sauce on it. They complain. Then I point out that Bizmuth is the only operative ingredient in

PeptoBizmol..all they gotta do is bite down hard on the little thingies in there they have been b-tching about and they will be cured!

doesn't work...I catch hell leaving the Chicom restaurant in the cold, rainy dark in the truck on the way to a warm and comfortable bed....which will

be disturbed by the non performing Bizmuth in the angry female belly....sigh.

The cost of the pneumonia and the "club," parka, hand warmers, waders. electric socks, candy bars and ear plugs and the $3000 shotgun and the

@2.75/round ammo and the $70 hunting license and the booze and the gas and the potential death in the fog/darkness all get forgotten and I come back

next year with the same three lunatics and the same wet dawg and the same female derision and condemnation for being an old and dumb S*&^t.

I'm a nut.

BB

|

|

|

djh

Senior Nomad

Posts: 936

Registered: 1-2-2005

Location: Earth mostly. Loreto, N. ID, Big Island

Member Is Offline

Mood: Mellow fellow, plays a yellow cello...

|

|

Wanna correct that?

| Quote: | Originally posted by Cypress

Got my tree stands ready, sighting-in my rifle next week. By the way, this morning a grizzly killed a bear hunter about 8 miles from where I live. One

of his hunting partners shot and killed the grizzly.  |

Cypress, Shouldn't you explain now what ACTUALLY happened up here?

In short: One of these two guys shoots a griz..... Griz gets rightly peeed and attacks.... The other guy starts shooting into the fracus and actually

shoots and kills his buddy....

Grizzly are seriously endangered in these parts, and avoid humans. Lots of griz have been killed in N. Idaho illegally... and the few remaining griz

in this population are literally hated by loggers, ATVers, and most hunters. The forecast for griz survival in the Selkirks and the Cabinet-Yak

populations is not good.... these critters don't need any more misinformation, bad press, and stupid (in)human(e) treatment.

I'm not wading into this dogfight over hunting, but I do believe it best that Cypress's earlier post gets corrected.

djh

Its all just stuff and some numbers.

A day spent sailing isn\'t deducted from one\'s life.

Peace, Love, and Music

|

|

|

djh

Senior Nomad

Posts: 936

Registered: 1-2-2005

Location: Earth mostly. Loreto, N. ID, Big Island

Member Is Offline

Mood: Mellow fellow, plays a yellow cello...

|

|

http://www.thewildlifenews.com/2011/09/23/sheriff-nevada-man...

If you need proof of just how schtoooopid this fiasco was!

Or this: http://www.kxly.com/news/29284271/detail.html

(might need to copy & paste the links.....)

There are still about 10 stories out there with "Grizzly attacks and kills hunter" to one correction "Hunter illegally shoots grizzly, then tracks the

injured grizzly that fled, gets attacked by the injured grizzly, and is shot and killed by his hunting companion".....

The sensational headline "Grizzly kills man" sells papers, while the truth has barely (pun intended) been told.

Its all just stuff and some numbers.

A day spent sailing isn\'t deducted from one\'s life.

Peace, Love, and Music

|

|

|

Pompano

Elite Nomad

Posts: 8194

Registered: 11-14-2004

Location: Bay of Conception and Up North

Member Is Offline

Mood: Optimistic

|

|

Meditations On Hunting

Fellow nomads, please take the time to read this entire essay on hunting by Sr. Gasset.

I think you may find that it portrays some honest and poignant statements about hunting and it's importance and effect towards modern mankind. Most

hunters I know have a copy at hand in thier library or gameroom. It's become a kind of primer, or bible if you will, for the outdoorsmen and nimrods.

'

'Meditations On Hunting

by Jose Ortega Y Gasset

(Thirty years ago Spain's eminent philosopher set down some thoughts about man's enduring pursuit of game. Now, for the first time, his essay has been

translated into English.)

"In our time—which is a rather stupid time—hunting is not considered a serious matter. It is thought a diversion, presupposing of course that

diversion as such is not a serious matter. How distasteful existence in the universe must be for a creature—man, for example—to find it essential to

divert himself, to attempt to escape for awhile from our real world to others that are not ours. Is this not strange? From what does man need to

divert himself? With what does he succeed in diverting himself? The question of diversion brings us more directly to the heart of the human condition

than do those great melodramatic topics with which demagogues berate us in their political speeches.

Now, however, I wish only to point out a feature of hunting that runs contrary to what is usually understood by diversion. The word usually refers to

ways of life completely free of hardship, free of risk, not requiring great physical effort nor a great deal of concentration. But the occupation of

hunting, as carried on by a good hunter, involves precisely all of those things. It is not a matter of his happening to go into the fields every once

in a while with his rifle on his shoulder; rather, every good hunter has dedicated a part of his existence—it is unimportant how much—to hunting. Now

this is a more serious matter. Diversion loses its passive character, its frivolous side, and becomes the height of activity. For the most active

thing a man can do is not simply to do something but to dedicate himself to doing it.

Throughout history, from Sumeria and Akkad, Assyria and the First Empire of Egypt up until the present, there have always been men, many men, who

dedicated themselves to hunting out of pleasure, will or affection. Seen from this point of view the topic of hunting expands until it attains

enormous proportions. Consequently, aware that it is a more difficult matter than it seems at first, I ask myself what the devil kind of occupation is

this business of hunting?

The life that we are given has its minutes numbered and, in addition, it is given to us empty. Whether we like it or not we have to fill it on our

own; that is, we have to occupy it one way or another. Thus the essence of each life lies in its occupations. The animal is given not only life but

also an invariable repertory of conduct. Without his own intervention, his instincts have already decided what he is going to do and what he is going

to avoid. Therefore it cannot be said that the animal occupies himself with one thing or another. His life has never been empty, undetermined. But man

is an animal who has lost his system of instincts, retaining only instinctual stumps and residual elements incapable of imposing on him a plan of

behavior. When he becomes aware of existence, he finds himself before a terrifying emptiness. He does not know what to do; he himself must invent his

own tasks or occupations. If he could count on an infinity of time before him, this would not matter very much, he could live doing whatever occurred

to him, trying every imaginable occupation one after another. But—and this is the problem—life is brief and urgent; above all, it consists in rushing,

and there is nothing for it but to choose one way of life to the exclusion of all others, to give up being one thing in order to be another; in short,

to prefer some occupations to the rest. The very fact that our languages use the word "occupation" in this sense reveals that from ancient times,

perhaps from the very beginning, man has seen his life as a space of time which his actions, like bodies of matter unable to penetrate one another,

continue to fill.

Along with life, there is imposed upon us a long series of unavoidable necessities that we must face unless we are to succumb. But the ways and means

of meeting these have not been imposed, so that even in this process of the inevitable we must invent—each man for himself or drawing from customs and

traditions—our own repertory of actions. Moreover, to what extent are those so-called vital necessities really vital? They are imposed upon us to the

extent that we want to endure, and we will not want to endure if we do not invent for our life a meaning, a charm, a flavor that in itself it does not

have. This is the reason I say that life is given to us empty. In itself life is insipid because it is a simple "being there." So, for man, existing

becomes a poetic task, like the playwright's or the novelist's: that of inventing a plot for his existence, giving it a character that will make it

both suggestive and appealing.

The fact is that for almost all men the major part of life consists of obligatory occupations, chores that they would never do out of choice. Since

this fate is so ancient and so constant, it would seem that man should have learned to adapt himself to it, and consequently to find it charming. But

he does not seem to have done so. Although the constancy of the annoyance has hardened us a little, these occupations imposed by necessity continue to

be difficult. They weigh upon our existence, mangling it, crushing it. In English such tasks are called jobs; in the Romance languages the terms for

them derive from the Latin word tripalium, which originally meant an instrument of torture. And what most torments us about work is that by filling up

our time it seems to take it from us; in other words, life used for work does not seem to us to be really ours, which it should be, but on the

contrary seems the annihilation of our real existence. We try to encourage ourselves with secondary reflections that attempt to ennoble work in our

eyes and to construct for it a kind of hagiographic legend, but deep down inside of us there is something irrepressible always functioning which never

abandons protest and which confirms the terrible curse of Genesis—"In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread." Hence the bad feeling we usually

inject into the term "occupation." When someone tells us that he is very occupied he is usually giving us to understand that his real life is being

held in suspension, as if foreign realities had invaded his world and left him without a home. This is true to such an extent that the man who works

does so with the more or less vague hope of one day winning through work the liberation of his life, of being able in time to stop working and start

really living.

All this indicates that man, painfully submerged in his work or obligatory occupations, projects beyond them, imagines another kind of life consisting

of very different occupations in the execution of which he would not feel as if he were losing time but, on the contrary, gaining it, filling it

satisfactorily and as it should be filled. Opposite a life that annihilates itself and fails—a life of work—he erects the plan of a life successful in

itself, a life of delight and happiness. While obligatory occupations seem like foreign impositions, to those others we feel ourselves called by an

intimate little voice that proclaims them from the innermost secret folds of our depths. This most strange phenomenon whereby we call on ourselves to

do specific things is the "vocation."

There is one general vocation common to all men. All men, in fact, feel called on to be happy, but in each individual that general call becomes

concrete in the more or less singular profile in which happiness appears to him. Happiness is a life dedicated to occupations for which that

individual feels a singular vocation. Immersed in them, he misses nothing; the whole present fills him completely, free from desire and nostalgia.

Laborious activities are performed not out of any esteem for them but rather for the result that follows them, but we give ourselves to vocational

occupations for the pleasure of them, without concern about the subsequent profit. For that reason we want them never to end. We would like to

eternalize them. And, really, once absorbed in a pleasurable occupation, we catch a starry glimpse of eternity.

So here is the human being suspended between two conflicting repertories of occupations: the laborious and the pleasing. It is moving and very sad to

see how the two struggle in each individual. Work robs us of time to be happy and pleasure gnaws away as much as possible at the time claimed by work.

As soon as man discovers a chunky or crack in the mesh of his work he escapes through it to the exercise of more enjoyable activities.

At this point a specific question demands our attention. What kind of happy existence has man tried to attain when circumstances allowed him to do so?

What have been the forms of the happy life? Even supposing that there have been innumerable forms, have not some been clearly predominant? This is of

the greatest importance because in the happy occupations, again, the vocation of man is revealed. Nevertheless, we notice, surprised and scandalized,

that this topic has never been investigated. Although it seems incredible, we lack completely a history of man's concept of what constitutes

happiness.

Exceptional vocations aside, we confront the stupefying fact that, while obligatory occupations have undergone the most radical changes, the idea of

the happy life has hardly varied throughout human evolution. In all times and places, as soon as man has enjoyed a moment's respite from his work he

has hastened, with illusion and excitement, to execute a limited and always similar repertory of enjoyable activities. Strange though this is, it is

essentially true; to convince oneself, it is enough to proceed rather methodically, beginning by setting out the information.

What kind of man has been the least oppressed by work and the most easily able to engage in being happy? Obviously, the aristocratic man. Certainly

the aristocrats, too, had their jobs, frequently the hardest of all: war, responsibilities of government, care of their own wealth. Only degenerate

aristocracies stopped working, and complete idleness was short-lived because the degenerate aristocracies were soon swept away. But the work of the

aristocrat, even though it entailed effort, was of such a nature that it left him a great deal of free time. And this is what concerns us: what does

man do when he is free to do what he pleases? Now this greatly liberated man, the aristocrat, has always done the same things: raced horses or

competed in physical exercises, gathered at parties, the feature of which is usually dancing, and engaged in conversation. But before any of those,

and consistently more important than all of them, has been...hunting. So that, if instead of speaking hypothetically we attend to the facts, we

discover—whether we want to or not, with enjoyment or with anger—that the most appreciated, enjoyable occupation for the normal man has always been

hunting. This is what kings and nobles have preferred to do: they have hunted. But it happens that the other social classes have done or wanted to do

the same thing, to such an extent that one could almost divide the felicitous occupations of the normal man into four categories: hunting, dancing,

physical endeavors and conversing.

Choose at random any period in the vast and continuous flow of history, and you will find that both men of the middle class and poor men have usually

made hunting their happiest occupation. No one better represents the intermediary group between the Spanish nobility and Spanish bourgeoisie of the

second half of the 16th century than the Knight in the Green-Colored Greatcoat, whom Don Quixote meets. In the plan of his life which he formally

expounds, this knight makes clear that "my exercises are hunting and fishing." A man already in his 50s, he has given up the hound and the falcon; a

partridge decoy and a bold ferret are enough for him. This is the least glorious kind of hunting, and it is understandable that Don Quixote shortly

afterward, in a gesture of impatience that distorted his usual courtesy, scorned both beasts in comparison with the husky North African lion.

One of the few texts on the art of hunting which has come down to us from antiquity is the Cynegeticus by Flavius Arrianus, the historian of Alexander

the Great and a Greek who wrote during the time of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. In this book, written during the first half of the second

century A.D., Arrianus describes the hunting expeditions of the Celts and in unexpected detail studies separately the potentate's way of hunting, the

middle-class man's way and the lower-class way. That is, everybody hunted—out of pleasure, it is understood—in a civilization that corresponds roughly

to the first Iron Age.

Nevertheless, the strongest proof of the extension throughout history of the enthusiasm for hunting lies in the contrary fact, namely, that with

maximum frequency throughout the centuries not everyone has been allowed to hunt. A privilege has been made of this occupation, one of the most

characteristic privileges of the powerful. Precisely because almost all men wanted to hunt and saw a possible happiness in doing so, it was necessary

to stagger the exercise of the occupation; otherwise the game would have very soon disappeared, and neither the many nor the few would have been happy

in that situation. It is not improbable, then, that even in the Neolithic period hunting acquired some of the aspects of a privilege. Neolithic man,

who is already cultivating the soil, who has tamed animals and breeds them, does not need, as did his Paleolithic predecessor, to feed himself

principally from his hunting. Freed of its obligatory nature, hunting is elevated to the rank of a sport. Neolithic man is already rich, and this

means that he lives in authentic societies, thus in societies divided into classes, with their inevitable "upper" and "lower." It is difficult to

imagine that hunting was not limited in one way or another.

Once we have underlined the almost universally privileged nature of the sport of hunting, it becomes clear to what extent this is no laughing matter

but rather, however strangely, a deep and permanent yearning in the human condition. It is as if we had poked a trigeminal nerve. From all the

revolutionary periods in history there leaps into view the lower classes' fierce hatred for the upper classes because the latter had restricted

hunting—an indication of the enormous appetite that the lower classes had for the occupation. One of the causes of the French Revolution was the

irritation the country people felt because they were not allowed to hunt, and consequently of the first privileges that the nobles were obliged to

abandon was this one. In all revolutions the first thing that the people have done was to jump over the fences of the preserves or to tear them down,

and in the name of social justice pursue the hare and the partridge. And this after the revolutionary newspapers, in their editorials, had for years

and years been abusing the aristocrats for being so frivolous as to spend their time hunting.

About 1938 Jules Romains, a hardened writer of the Front Populaire, published an article venting his irritation with the workers because they, having

gained a tremendous reduction in the workday and being in possession of long idle hours, had not learned to occupy themselves other than in the most

uncouth form of hunting: fishing with a rod, the favorite sport of the good French bourgeois. The ill-humored writer was deeply irritated that a

serious revolution had been achieved with no apparent result other than that of augmenting the number of rod fishermen.

The chronic fury of the people against the privilege of hunting is not, then, incidental or mere subversive insolence. It is thoroughly justified: in

it the people reveal that they are men like those of the upper class and that the vocation, the felicitous illusion, of hunting is normal in the human

being. What is an error is to believe that this privilege has an arbitrary origin, that it is pure injustice and abuse of power. No, we shall

presently see why hunting—not only the luxurious sporting variety but any and all forms of hunting—essentially demands limitation and privilege.

Argue, fight as much as you like, over who should be the privileged ones, but do not pretend that squares are round and that hunting is not a

privilege. What happens here is just what has happened with many other things. For 200 years Western man has been fighting to eliminate privilege,

which is stupid because in certain orders privilege is inevitable and its existence does not depend on human will. It is to be hoped that the West

will dedicate the next two centuries to fighting—there is no hope for a suspension of man's innate pugnacity—to fighting for something less stupid,

more attainable and not at all extraordinary, such as a better selection of privileged persons.

In periods of an opposite nature, which were not revolutionary and in which, avoiding false Utopias, people relied on things as they really were, not

only was hunting a privilege respected by all, but those on the bottom demanded it of those on top, because they saw in hunting, especially in its

superior forms—the chase, falconry and the battue [the practice of beating the woods to drive the game from cover]—a vigorous discipline and an

opportunity to show courage, endurance and skill, which are the attributes of the genuinely powerful person. Once a crown prince who had grown up in

Rome went to occupy the Persian throne. It is said that very soon he had to abdicate because the Persians could not accept a monarch who did not like

hunting, a traditional and almost titular occupation of Persian gentlemen. The young man apparently had become interested in literature and was beyond

hope.

Hunting, like all human occupations, has its different levels, and how little of the real work of hunting is suggested in words like diversion,

relaxation, entertainment! A good hunter's way of hunting is a hard job that demands much from man: he must keep himself fit, face extreme fatigues,

accept danger. It involves a complete code of ethics of the most distinguished design; the hunter who accepts the sporting code of ethics keeps these

commandments in the greatest solitude with no witnesses or audience other than the sharp peaks of the mountain, the roaming cloud, the stern oak, the

trembling juniper and the passing animal. In this way hunting resembles the monastic rule and the military order. So in my presentation of it as what

it is, as a form of happiness, I have avoided calling it pleasure. Doubtless in all happiness there is pleasure, but pleasure is the least of

happiness. Pleasure is a passive occurrence, and it is appropriate to return to Aristotle, for whom happiness always clearly consisted in an act, in

an energetic effort. That this effort, as it is being performed, produces pleasure is only coincidental and, if you wish, one of the ingredients that

comprise the situation. But along with the pleasures that exist in hunting, there are innumerable annoyances. What right have we to take it by that

handle and not by this one? The truth is that the important and appealing aspect of hunting is neither pleasure nor annoyance but rather the very

activity that comprises hunting.

Happy occupations, it is clear, are not merely pleasures; they are efforts, and real sports are effort. It is not possible to distinguish work from

sport by a plus or minus in fatigue. The difference is that sport is an effort made freely, for the pure enjoyment of it, while work is an obligatory

effort made with an eye to the profit.

Anyone who is now advanced in years has had the opportunity to observe that from his childhood to the present the number of animals that the human

hunter has found interesting and considered worthwhile pursuing as quarry has greatly diminished. To explain this, obvious reasons have been given:

the greater perfection of weapons, the excessive number of hunters that use them, the growing area of cultivated lands not only in Europe but

throughout the world. Whether or not these are the causes, the diminution itself is fact, and once reality has forced us to accept it as such, it

triggers in us an abstract line of reasoning. If in our childhood there was more game than today, going backward in time we should find greater and

greater abundance, and we should presently arrive at times in which it must have been superabundant. This is how we have got into our heads, almost

automatically, the common conviction that "before, there was much more game," in the sense that "there was more than enough game." I myself used to

accept this like everyone else.

Prehistorians usually affirm that the various glacial and postglacial periods were paradise for the hunter. They give us the impression that tasty

prey swarmed everywhere in unimaginable abundance and, reading their works, the wild animal that dozes deep down inside any good hunter feels his

teeth sharpen and his mouth water. But those appraisals are vague and summary. At times a precise bit of information, in which we are given figures,

leads us to imagine swarms of animals. Thus the remains of some 10,000 wild horses have been found in what is perhaps the largest-known field of prey,

the region around Solutr�. In the Drachenh�hle (Cavern of Dragons) in Styria, says Hugo Obermaier, the German archaeologist, 30,000 to

50,000 skeletons of cave-dwelling bears were piled up, dead not at the hands of hunters but due to natural causes.

But prehistorians use a chronology that walks on very tall stilts. They speak of millennia as if they were nothing. The durations of which they speak,

like those of astronomers, are expressed in such large figures that the whole beauty of numbers evaporates, becoming mere convention. In fact, to the

aforementioned data about the bears, Obermaier immediately adds, "Since more than five or six families never lived together at the same time in the

cave, it is to be assumed that the Drachenh�hle was the constant dwelling place of these animals for more than 10,000 years." The highly

respected Obermaier is now being reasonable. But if we take the smaller figure, as would be sane, 30,000 divides up into three bears a year. This is

too few bears: it is what I call the scarcity of game.

To gauge the quantity of game that presumably existed in the Paleolithic Age, the documents which the hunters of that time left us in their rock

figurations are, for many problematic reasons, more important than these facts. This is because those exciting images were put there, paralyzed in

stone, not for love of art but for a magical purpose. By covering the walls with drawings of animals, ritually consecrated, primitive man believed he

assured the animals' presence in the environs. By drawing an arrow in the flank of an image a successful hunt was prefigured. This magic was not only

meant to achieve success in wounding the prey, it was also fertility magic. The figurative rite was performed so that the animal would be abundant and

its females fertile.

It would be appropriate to state precisely the three purposes of this hunting magic: 1) that there be a lot of game; 2) given it exists, that the

hunter find it; 3) once found, that the techniques used to capture it—the trap, driving it off a cliff, the dart, the arrow—function successfully.

With the first purpose the primitive hunter makes a formal and explicit confession to us that he did not believe game to abound, so that for him the

first act of hunting consists in procuring the existence of game, which apparently on its own was simply neither plentiful nor constant.

But the other two purposes implicitly declare just as much that this hunter starts from the assumption that the desired animal is uncommon. If it were

plentiful there would be no question of not running into it, no problems and hardships seeking it. If it is unnecessary to look for it because it is

always at hand, in inexhaustible supply, one does not worry either about success in killing or capturing it. If the first blow fails it is all the

same; another animal is close by to receive a second aggression, and so on indefinitely.

But this last inference, which is of superlative simplicity and if well understood would seem to be a platitude, leads to a sudden realization. It

dawns on us that this kind of arduous proof of scarcity of game throughout human history, and still earlier in prehistory, is completely unnecessary;

we could have saved ourselves the trouble with a simple reflection on the very idea of the hunt.

For hunting is not simply casting blows right and left in order to kill animals or to catch them. The hunt is a series of technical operations, and

for an activity to become technical it has to matter that it works in one particular way and not in another. Technique presupposes that success in

reaching a certain goal is difficult and improbable; to compensate for its difficulty and improbability one must exert oneself to invent a special

procedure of sufficient effectiveness. If we take one by one the different acts that comprise hunting, starting with the last—killing or capturing the

prey—and continuing backward toward the initial operation, we will see that they all presuppose the scarcity of game.

Anybody who has hunted will recognize that each prey when it appears seems as if it is going to be the only one. It is a flash of opportunity the

hunter must take advantage of. Perhaps the occasion will not present itself again all day. Thus the excitement, always new, always fresh, even in the

oldest hunter. But all this presupposes that achieving the presence of game is a triumph in itself, and very unusual good fortune. But how many

efforts are necessary in order to have this fortunate opportunity, as instantaneous as a lightning flash, take place! The chain of venatic operations

unfolds now before our retrospective analysis. And each technique is revealed as a difficult and ingenious effort to force the appearance of the

animal, which apparently on his own characteristically will not be there. So, leaving aside the magic used by the primitives of the glacial period,

the first act of all hunting is to find the prey. Strictly speaking, this is not merely the first task, but the fundamental task of all hunting:

bringing about the presence of the prey.

The Paleolithic tribes of the present—those that live, like those of 10,000 years ago, exclusively or almost exclusively by hunting—are the most

primitive human species that exist. They do not have the slightest hint of government, of legislation, of authority; only one law is enforced among

them: that which determines how they must divide the spoils of their hunting. In many of these tribes the largest and best portion of the spoils is

given not to the one who kills, but rather to the one who first saw the animal, discovered it and caused it to rise and show itself. It is almost

certain that this was the "constitutional right" of hunting in the dawn of humanity. That is, when the history of hunting began, detecting the animal

was already held to be the basic operation; therefore the scarcity of game is of the essence of the whole undertaking. There is no more eminent proof

that this initial labor is the most important part of hunting, and it is understandable that a very accomplished hunter should consider the supreme

form of hunting that in which the hunter, alone in the mountains, is at the same time the person who discovers the prey, the one who pursues it and

the one who fells it.

So we have come to a monumental but inevitable paradox: the fact that man hunts presupposes that there is and always has been a scarcity of game. If

game were superabundant, there would not exist that peculiar animal behavior that we distinguish from all others with the precise name "hunting."

Since air is usually abundant, there is no technical ability involved in breathing, and breathing is not hunting air.

More than once the sportsman within shooting range of a splendid animal hesitates in pulling the trigger. The idea that such a slender life is going

to be annulled surprises him for an instant. Every good hunter is uneasy in the depths of his conscience when faced with the death he is about to

inflict on the enchanting animal. He does not have the final and firm conviction that his conduct is correct. But neither, it should be understood, is

he certain of the opposite. Finding himself in an ambivalent situation which he has often wanted to clear up, he thinks about this issue without ever

obtaining the sought-after evidence. I believe that this has always happened to man, with varying degrees of intensity according to the nature of the

prey—ferocious or harmless—and with one or another variation in the aspect of uneasiness. This says nothing against hunting but only that the

generally problematic, equivocal nature of man's relationship with animals shines through that uneasiness. Nor can it be otherwise, because man really

has never known exactly what an animal is. Before and beyond all science, humanity sees itself as something emerging from animality, but it cannot be

sure of having transcended that state completely. The animal remains too close for us to not feel mysterious communication with it. The only people to

have felt they had a clear idea about the animal were the Cartesians. The truth is that they believed they had a clear idea about everything. But to

achieve that rigorous distinction between man and beast, Descartes first had to convince himself that the animal was a mineral—that is, a mere

machine. Fontanel le recounts that in his youth, while he was visiting Malebranche, a pregnant dog came into the room. So that the animal would not

disturb anyone who was present, Malebranche—a very sweet and somewhat sickly priest whose spine was twisted like a corkscrew—had the dog expelled with

blows from a stick. The poor animal ran away howling piteously while Malebranche, a Cartesian, listened impassively. "It doesn't matter," he said.

"It's a machine, it's a machine!"

Has anyone noticed the very strange fact that, before and apart from any moral or even simply compassionate reaction, it seems to us that nothing

stains as blood does? When two men who have had a fistfight in the street finally separate and we see their bloodstained faces, we are always

disconcerted. Rather than producing in us the sympathetic response which another's pain generally causes, the sight creates a disgust that is

extremely intense and of a very special nature. Not only do those faces seem repugnantly stained, but the filth goes beyond physical limits and

becomes, at the same time, moral. The blood has not only stained the faces but it has soiled them—that is to say it has debased and in a way degraded

them. Hunters who read this will remember this primary sensation, so often felt, when at the end of the hunt the dead game lies in a heap on the

ground with dried blood here and there staining plumage and pelt. The reaction, I repeat, is prior to and still deeper than any ethical question,

since one notices the degradation that blood produces wherever it falls, on inanimate things as well. Earth that is stained with blood is as damned. A

white rag stained with blood is not only repugnant, it seems violated, its humble textile material dishonored. It is the frightening mystery of blood.

What can it be? Life is the mysterious reality par excellence, not only in the sense that we do not know its secret but also because life is the only

reality that has a true "inside"—an intus or intimacy. Blood, the liquid that carries and symbolizes life, is meant to flow occultly, secretly,

through the interior of the body. When it is spilled and the essential "within" comes outside, a reaction of disgust and terror is produced in all

nature, as if the most radical absurdity had been committed: that which is purely internal made external.

But this is precisely what death is. The cadaver is flesh that has lost its intimacy, flesh whose "interior" has escaped like a bird from a cage, a

piece of pure matter in which there is no longer anyone hidden.

Yet after this first bitter impression, if the blood insists on presenting itself, if it flows abundantly, it ends by producing the opposite effect:

it intoxicates, excites, maddens both man and beast. The Romans went to the circus as they did to the tavern, and the bullfight public does the same:

the blood of the gladiators, the beasts, the bull operates like a stupefying drug. Similarly, war is always an orgy at the time. Blood has an

unequaled orgiastic power.

I have indicated that a sport is the effort which is carried out for the pleasure that it gives in itself and not for the transitory result that the

effort brings forth. It follows that when an activity becomes a sport, whatever that activity may be, the hierarchy of its values becomes inverted. In

utilitarian hunting the true purpose of the hunter, what he seeks and values, is the death of the animal. Everything else that he does before that is

merely a means for achieving that end, which is its formal purpose. But in hunting as a sport, this order of means to end is reversed. To the

sportsman the death of the game is not what interests him; that is not his purpose. What interests him is everything he had to do to achieve that

death—that is, the hunt. Therefore what was before only a means to an end is now an end in itself. Death is essential because without it there is no

authentic hunting: the killing of the animal is the natural end of the hunt and the goal of hunting itself, not of the hunter. The hunter seeks this

death because it is no less than the sign of reality for the whole hunting process. To sum up, one does not hunt in order to kill; on the contrary,

one kills in order to have hunted. If one were to present the sportsman with the death of the animal as a gift, he would refuse it. What he is after

is having to win it, to conquer through his own effort and skill with all the extras that this carries with it: the immersion in the countryside, the

healthfulness of the exercise, the distraction from his job and so on and so forth.

In order to subsist, early man had to dedicate himself wholly to hunting. Hunting was the first occupation, man's first work and craft. The venatic

occupation was unavoidable, and as the center and root of existence it ruled human life completely—its acts and its ideas, its technology and

sociality. Hunting was, then, the first form of life man adopted, and this means—it should be fundamentally understood—that man's being consisted

first in being a hunter.

Primitive hunting, however, was not a pure invention of primitive man. He had inherited it from the primate animal from which the human peculiarity

sprang. Do not forget that man was once a beast. His carnivore's fangs and canine teeth are unimpeachable evidence of this. Of course, he was also a

vegetarian, like the ovidae, as his molars attest. Man, in fact, combines the two extreme conditions of the mammal, and therefore he goes through life

constantly vacillating between being a sheep and being a tiger.

Early Paleolithic man, the oldest that we know and the one who by chance was the hunter par excellence, was a man while still an animal. His reason

was not sufficient to permit him to transcend the orbit of zoological existence; he was an animal intermixed with discontinuous lucidities, a beast

whose intellect glowed from time to time in his intimate darkness. Such was the original, primordial way of being a man.

In these conditions he hunted. All the instincts that he still had played a part in his task, but in addition he employed thoroughly all his reason.

This is the only form of hunting, among all those that man has practiced, which can truly be called a "reasoned pursuit." It can be called that even

though it was not especially reasoned. Nevertheless, the first traps were invented in that period. From the first, man was a very tricky animal. And

he invented the first venatorial stratagems: for example, the battue, which drove the game toward a precipice. The early weapons were insufficient for

killing the free animal. Hunting was either forcing the game over a cliff or capturing it in traps or with nets and snares. Once the prey was caught,

it was beaten to death. Obermaier thinks that sometimes it was suffocated with clouds of smoke.

Starting from this outline we must conceive the later development. To do that it is necessary to think along two lines at once. Reason grows stronger.

Man invents more and more effective weapons and techniques. In this direction man grows farther away from the animal, raising his level above that of

the beast. But along parallel lines, the atrophy of his instincts increases also, and he grows away from his pristine intimacy with nature. From being

essentially a hunter he passes to being essentially a shepherd—that is, to a semistationary way of life. Very soon he turns from shepherd into farmer,

which is to say that he becomes completely stationary. The use of his legs, his lungs, his senses of smell, of orientation, of the winds, of the

trails all diminish. Normally, he ceases to be an expert tracker. This reduces his advantage over the animal; it maintains him in a limited range of

superiority that permits the equation of the hunt. As he has perfected his weapons he has ceased to be wild; he has lost form as a fieldsman. The man

who uses a rifle today generally does not live continuously on plains or in forests; rather, he goes there only for a few days. Today's best-trained

hunter cannot begin to compare his form to that of the sylvan actions of the present-day pygmy or his remote counterpart, Paleolithic man. Thus

progress in weaponry is somewhat compensated by regression in the form of the hunter.

The admiration and generous envy that some modern hunters feel toward the poacher stems from this. The poacher is, in distant likeness, a Paleolithic

man—the municipal Paleolithic man, the eternal cave dweller domiciled in modern villages. His greater frequentation of the mountain solitudes has

reeducated a little the instincts that have only a residual nature in urban man. This reconfirms the idea that hunting is a confrontation between two

systems of instincts. The poacher hunts better than the amateur not because he is more rational but because he tires less, he is more accustomed to

the mountains, he sees better and his predatory instincts function more vigorously. The poacher always smells a little like a beast and he has the

eyesight of a fox, a marten or a field mouse. The sporting hunter, when he sees a poacher at work in the field, discovers that he himself is not a

hunter, that in spite of all his efforts and enthusiasm he cannot penetrate the solid profundity of venatorial knowledge and skill the poacher

possesses. It is the superiority of the professional, of the man who has dedicated his entire life to the matter, while the amateur can only dedicate

a few weeks of the year to it. We must immerse ourselves wholly and heroically in an occupation in order to dominate it, to be it!

Very soon reason reaches a degree of development that permits human life to go beyond the horizon of the animal; thus when man's superiority becomes

almost absolute, the role of reason in the hunt becomes inverted. Instead of being used fully and directly in the task, it intervenes rather obliquely

and gets in its own way. Adult reason directs itself to tasks other than hunting. When it does bother with the hunt, it pays most attention to

preliminary or peripheral questions. It seriously will endeavor to improve the species by scientific means, to select the breeds of dogs, to dictate

good laws for the hunt, to organize the game preserves and even to produce weapons that within very narrow limits will be more accurate and effective.

But one idea presides over all this: the inequality between hunter and hunted should not be allowed to become excessive, the margin that existed

between them at the beginning of history will be preserved and, where possible, improved in favor of the animal. On the other hand, when the moment of

the hunt actually arrives, reason does not intervene in any greater degree than it did in primitive times, when it was no more than an elemental

substitute for the instincts. This clarifies the fact, incomprehensible from any other point of view, that the general lines of the hunt are identical

today with those of 5,000 years ago.

Thus the principle which inspires hunting for sport is that of artificially perpetuating a situation which is archaic in the highest degree: that

early state in which, already human, man still lived within the orbit of animal existence.

It is possible that I may have offended some hunter who presumes that my definition of hunting implies I have treated him as an animal. But I doubt

that any real hunter will be offended. For all the grace and delight of hunting are rooted in this fact: that man, projected by his inevitable

progress away from his ancestral proximity to animals, vegetables and minerals—in sum, to nature—takes pleasure in the artificial return to it, the

only occupation that permits him something like a vacation from his human condition. Thus the meditation which unfolds in the preceding pages has gone

full circle, returning us to its beginning, because it means that when man hunts he succeeds in diverting himself and in distracting himself from

being a man. And this is the superlative diversion: it is the fundamental diversion.

There is no period in which this nostalgia for other past times has not existed because there has never been a period in which man felt that he had

more than enough energy to deal with his own troublesome situation. He has always lived with the water at his throat. The past is a promise of greater

simplicity for him: it seems to him that he could move with a good deal more comfort and prepotency in those less-evolved forms of primitive life.

Life would be a game for him.

It is surprising to see the insistence with which all cultures, upon imagining a golden age, have placed it at the beginning of time, at the most

primitive point. It was only a couple of centuries ago that the tendency to expect the best from the future began to compete with that retrospective

illusion. Our hearts vacillate between a yearning for novelties and a constant eagerness to turn back. But historically the latter predominates.

Happiness has generally been thought to be simplicity and primitivism.

As history advanced, the ways of being a man became more conditioned—we would say more specialized. On the other hand, if we move backward toward more

and more elemental styles of life, specialization diminishes and we find more generic ways of being a man, with so few suppositions that in principle

those ways would be possible or almost possible in any time; that is, they exist as permanent availabilities in man.

This is the reason men hunt. When one is fed up with the troublesome present, with being very 20th century, one takes his gun, whistles for his dog,

goes out to the mountain and, without further ado, gives himself the pleasure during a few hours or a few days of being Paleolithic. And men of all

eras have been able to do the same without any difference except in the weapon employed. It has always been at man's disposal to escape from the

present to that pristine form of being a man which, because it is the first form, has no historical suppositions. History begins with that form.

By hunting, man succeeds, in effect, in annihilating all historical evolution, in separating himself from the present and in renewing the primitive

situation. An artificial preparation is necessary, certainly, for hunting to be possible. It is even necessary for the state to intervene, protecting

the preserves or imposing the closed seasons without which there would be no game. But what is artificial in hunting remains prior to, and outside of,

hunting itself. When modern man sets out to hunt, what he does is essentially the same thing Paleolithic man did. The only difference is that for the

latter hunting was the center of gravity for his whole life, while for the sportsman it is only a transitory suspension, almost parenthetical, of his

authentic life. The hunter is, at one and the same time, a man of today and of 10,000 years ago. In hunting, the long process of universal history

coils up and bites its own tail."

I do what the voices in my tackle box tell me.

|

|

|

Cypress

Elite Nomad

Posts: 7641

Registered: 3-12-2006

Location: on the bayou

Member Is Offline

Mood: undecided

|

|

Pompano, Guess that explains why hunting is one of my favorite activities. Keep the pics and info coming. Thanks!

djh, Thanks for posting the "new" info about the man/grizzly killing. My earlier post was based on the info available at the time. I agree with you

about the plight of the grizzly and the need for continued protection. BTW my rifle is sighted in. Hit a clay pigeon embedded in a dirt bank at 265

yards, no sweat.

bufeo, You bet!!

|

|

|

ELINVESTIG8R

Select Nomad

Posts: 15882

Registered: 11-20-2007

Location: Southern California

Member Is Offline

|

|

|

|

|

LaTijereta

Super Nomad

Posts: 1192

Registered: 8-27-2003

Location: Loreto

Member Is Offline

|

|

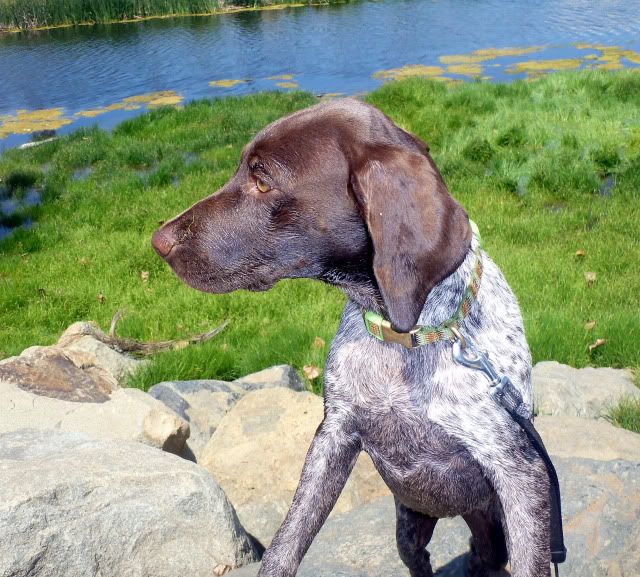

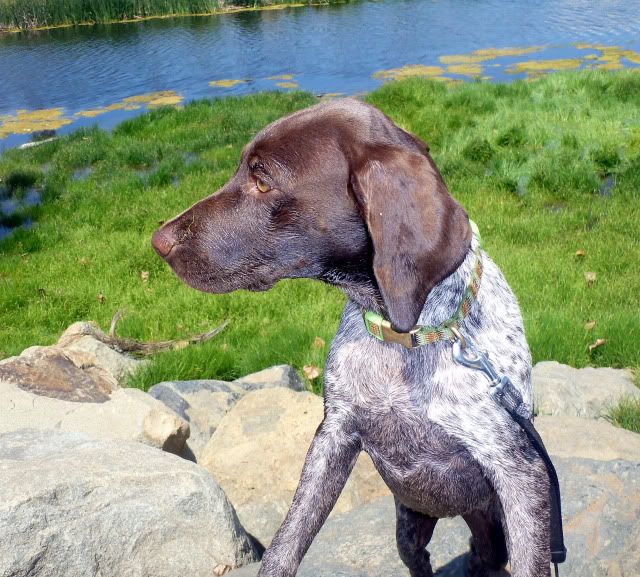

Pomp... Love the pics of the bird dogs in action..

I have a new pup (16 weeks) in training here ..

Loves the water.. and has good "bird sense"

Unfortunatly, she is training at Buena Vista lagoon in South Oceanside...

Her next adventure will be her first trip down to Baja later this month...

Democracy is like two wolves and a lamb voting on what to have for lunch. Liberty is a well-armed lamb contesting the vote.

Ben Franklin (1759)

|

|

|

bufeo

Senior Nomad

Posts: 793

Registered: 11-16-2003

Location: Santa Fe New Mexico

Member Is Offline

|

|

Nice looking GSH, LT.

Allen R

|

|

|

BajaRat

Super Nomad

Posts: 1304

Registered: 3-2-2010

Location: SW Four Corners / Bahia Asuncion BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: Ready for some salt water with my Tecate

|

|

" But WHY do you always miss the first honker of the season?? And… Maybe you can carry my shotgun & thermos to my blind for me? "

He wants to let you get first shot DAD!

|

|

|

BajaRat

Super Nomad

Posts: 1304

Registered: 3-2-2010

Location: SW Four Corners / Bahia Asuncion BCS

Member Is Offline

Mood: Ready for some salt water with my Tecate

|

|

Looks like fond memories.

|

|

|

durrelllrobert

Elite Nomad

Posts: 7393

Registered: 11-22-2007

Location: Punta Banda BC

Member Is Offline

Mood: thriving in Baja

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by BajaRat

" But WHY do you always miss the first honker of the season?? |

No honkers where I live but I never miss the first shot:

Bob Durrell

|

|

|

Pompano

Elite Nomad

Posts: 8194

Registered: 11-14-2004

Location: Bay of Conception and Up North

Member Is Offline

Mood: Optimistic

|

|

| Quote: | Originally posted by LaTijereta

Pomp... Love the pics of the bird dogs in action..

I have a new pup (16 weeks) in training here ..

Loves the water.. and has good "bird sense"

Unfortunatly, she is training at Buena Vista lagoon in South Oceanside...

Her next adventure will be her first trip down to Baja later this month...

|

Gorgeous pup. La Tijereta..truly great form & stance.

You have your Maya in a great place for a shorthair...full of bird scents. I know that Oceanside area well, and I'll be taking my morning walks along

the seaside-lagoon in a couple weeks, plus enjoying Gaucome Park and all the birds and animals there. An oasis in the middle of a congested SoCaL

beach area, where I slowly unwind from I-5 and the like.

I have a soft spot in my heart for those shorthairs, having fished the Cortez often with a nice hunting/fishing pair, Chile & Pepper.

They have super personalities and are quite different.

Pepper loves the water too, and would like to swim like a fish for hours.....plus ride this porpoise if it comes just a bit closer!

Chili is outstanding as a strong, never-tiring hunter..... PLUS being a big lover.

Many years ago, I had a great shorthair named Bob...whose nose was phenomenal, but being deaf as a stone did not help his game. I loved him anyway.

Our star retriever this week at the Duk Shak is 'Sam'...and as you can see, he loves what he does.....and he does it well!

Cheyenne, my chocolate lab, is a pack rat and likes to show off her hoard.

The Boys have their own style of Action.

The jury's still out on just what kind of retrieve the Maltese Brothers will make for me? (Psst..Boys, go fetch a kindred spirit

who cooks duck.).

[Edited on 10-4-2011 by Pompano]

I do what the voices in my tackle box tell me.

|

|

|

| Pages:

1

..

6

7

8

9 |

|